An unlikely atheist teaches others

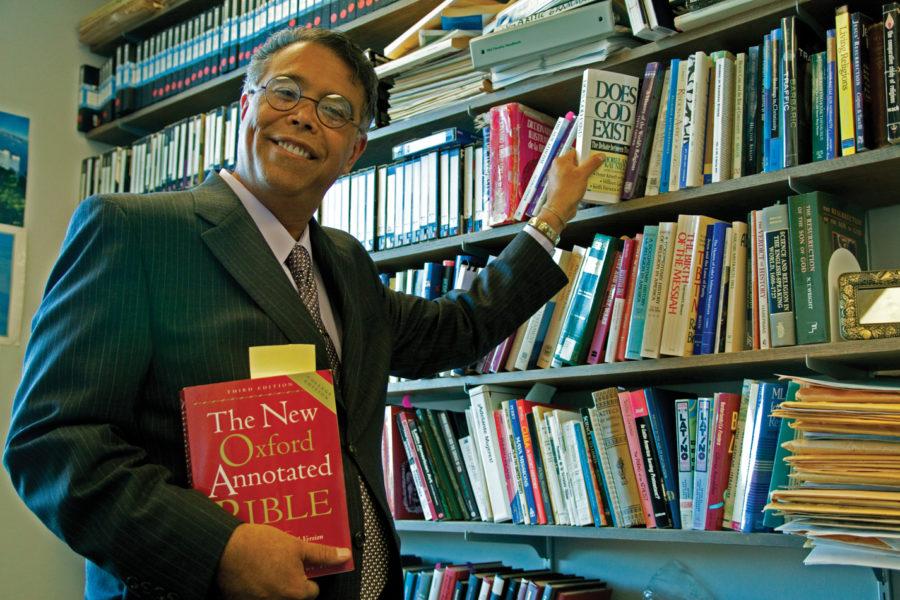

Bryan Langfeldt/Iowa State Daily

Hector Avalos, professor of philosophy and religious studies, explains his reasoning and logic regarding being an atheist. His curiosity in researching the background of Christianity has changed his beliefs to atheism.

November 9, 2010

Hector Avalos doesn’t drink. He doesn’t smoke or gamble, either.

Avalos, professor of philosophy and religious studies, has been studying the Bible since he was a child. In fact, he was a child evangelist preacher.

He’s also atheist or agnostic, depending on how one defines the word “God.”

“Most people would say I look a lot like a conservative Christian,” Avalos said. “[I’m] not what they would expect an atheist to [look like].”

With a master’s degree in theological studies and a doctorate in biblical studies from Harvard University, Avalos describes himself as a positive person who loves to learn and teach. He believes the purpose of all knowledge is to help people and said his favorite thing to do is spend time with his wife.

Avalos is the founder and faculty adviser of the Atheist and Agnostic Society on campus. He has written eight books on three topics: violence in religion, religion among Latinos and medical patients in the ancient world.

While growing up, Avalos’ zealous belief in God ignited an intense study of the Bible.

“I started by trying to defeat the arguments of the other side,” Avalos said, “and in the process I realized that my own arguments were not very good.”

Born in Nogales, Sonora, Mexico, in 1958, Avalos attended the Church of God, a Pentecostal church. He said as a child he had powerful “spiritual experiences,” which he now says were caused by socio-psychological factors.

Avalos moved to Glendale, Ariz., to live with his grandmother when he was 7 years old. He became a child preacher, speaking about God before congregations of hundreds of people.

“We talked about sin and salvation,” Avalos said. “That you needed to be saved because Jesus died for your sins, and it will help you transform your life. We were against abortion. We were against pre-marital sex. We were against homosexuality. We were against rock ‘n’ roll.”

Avalos said he was determined to become a Christian missionary. In a testimonial which appeared in Freethought Today, a newspaper published by the Freedom from Religion Foundation, Avalos wrote, “By my early teens, I was a zealous believer, willing to go anywhere, to suffer any sacrifice to preach the word of salvation to the ‘pagan’ masses.”

When a Jehovah’s Witness told him the Bible was mistranslated from its original Greek and Hebrew text, however, Avalos turned to studying in order to defend his beliefs.

“I realized that to be a missionary for Christianity, you had to become a biblical scholar. You had to know the arguments of the other sides as well.”

Avalos taught himself Greek and Hebrew and studied Aramaic, Akkadian, philosophy, theology and Near-Eastern history.

“Most adults, up until recently, usually end up in the religion they were raised in,” Avalos said. “It’s not because they came to that religion through a long period of study or research, but they were just raised that way. To me that was not satisfactory. I wanted to know whether it was true or not.”

The more he learned, however, the more he began to question his faith. During his freshman year of college at Glendale Community College, he reached a kind of epiphany.

“Through the process of years of studying,” Avalos said, “I came to the conclusion that the arguments I made for Christianity were not the best, and that I could make just as excellent of an argument for other religions as I could for mine.

“One thing led to another, and I realized that I did not believe in Christianity or that the Bible was the word of God, or that the Bible had any kind of divine origin.”

Avalos said he also had a problem with the ethics of the Bible, including the endorsement of genocide, slavery and killing of children. He also could not find any evidence that the Bible was factual.

“What I thought were very well-documented arguments with sources from their time turned out to have no sources,” Avalos said. “I thought there would be plenty of evidence for the life and doings of Jesus from his time. There are actually no documents from the time of Jesus about him.”

Around the same time that Avalos reached his realizations, he became very ill.

What had begun as a cold progressed into early systemic arthritis and conjunctivitis. Eventually, Avalos was diagnosed with Wegener’s Granulomatosis, a rare auto-immune disorder.

Behind in school because of his illness, Avalos asked professors in biology, German and Hebrew at the University of Arizona if they would give him full credit for courses he had never taken if he passed the final exams. They said “yes,” and Avalos passed them all because of his program of self-study in high school.

“Altogether, my first semester back I took 45 credits and was able to finish my sophomore, junior and senior year in three semesters,” Avalos said. “One of my professors said, ‘You should be at Harvard.'”

Through good grades, recommendations and academic scholarships, Avalos made it to Harvard. There, he earned a master’s degree in theological studies and was accepted into the Ph.D. program before becoming ill again. Avalos’ doctors gave him two years to live.

“There is this old adage that says there are no atheists in foxholes,” Avalos said. “The idea is that when you’re faced with death, you become a believer. Well, I have faced death many times because of my illness. What has helped me is what I see helping me, which is medical science and my family.”

Avalos decided to press on in his studies and earned his doctorate in 1991, making him the first Mexican-American to get a Ph.D. at Harvard in biblical studies. Despite his credentials, however, Avalos struggled to find a job. Because of his illness, he was severely disabled, and he struggled to breathe and speak.

“Hardly anyone would hire me,” Avalos said, “until I came to Iowa State.”

Avalos began teaching biblical studies at Iowa State in 1993 and Latino studies in 1994. He said Iowa State was very accommodating to his disorder, giving him a classroom right across the hall from his office in Ross Hall.

In 1999, Avalos founded a new organization called the Atheist and Agnostic Society.

“Prior to ’99, the word ‘atheist’ was like a dirty word,” Avalos said. “It still is, actually. People were reluctant to call themselves atheists, so they would call themselves skeptics or free-thinkers. I believe we were the first group to openly call ourselves the Atheist and Agnostic Society.”

AAS celebrated its 10th anniversary last year. The organization was featured in an article in USA Today as a leader among secular groups.

“We started out alone, and now there are many groups across the nation identifying themselves as atheist and agnostic,” Avalos said. “These groups are meant to serve the needs of non-religious students.”

Kristoffer Scott, junior in electrical engineering and president of AAS, said one of the group’s goals is to humanize atheism and show that it is a valid world view.

“We’re here to give an opportunity to everyone to speak their mind on religious matters without worrying about people condemning their views,” Scott said.

In his biblical classes, Avalos said he has his students debate religious topics, such as the resurrection of Jesus.

“His teaching style really encourages me to look deeper into texts and not take things at face value,” said Kristian Kline, senior in pre-business and one of Avalos’ students. “He’s a unique professor in that his class is largely based on group discussion.”

Sarah Hilz, senior in sociology, has taken four courses with Avalos and said he’s very respectful of all religious beliefs.

“He’s a challenging professor, and he’s kind of intimidating at first,” Hilz said. “But he makes you want to learn things and work hard in his classes.”

Avalos said his courses are not meant to convert students to atheism but rather to show different perspectives of the Bible.

“A lot of these kids come here not even knowing there are other viewpoints,” Avalos said. “That in itself is an eye-opening experience for them.”

Avalos said he loves to teach and believes that all knowledge is meant for helping people.

“For all the scholarship that you can do, there’s nothing more important than learning those things that make your relationships better with your wife or your children or your parents. And if you have a Ph.D. and you can’t do that … that’s one of the problems I see in society.”

When Avalos tells people that he is a professor in biblical studies, he’s often asked what denomination he claims. People tend to be confused when he explains that he is atheist, but he is always willing to share his story. Avalos began his religious studies to defeat any argument against his faith in God. These studies led him instead to a faith in science and in family.

“If you have someone who loves you as much as you love them, that’s about as good as it gets in life,” Avalos said. “If that doesn’t get you through, I don’t know what else can get you through.”

The following corrections have been applied to this story:

Professor Hector Avalos’ office is in Ross Hall, not Catt Hall.

He started teaching at Iowa State in 1993, not 1994. He started teaching Latino studies in 1994.

He had problems with the ethics of the Bible, not the ethics of religion.

He was attending Glendale Community College during his freshman year when he became ill. He attended University of Arizona his sophomore year.