The colors of peace

October 10, 2010

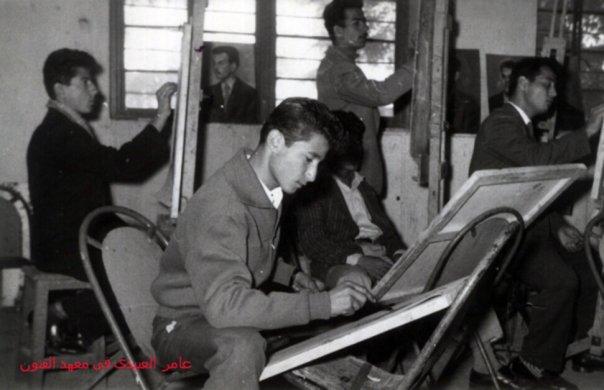

To know Amer al-Obaidi is to spend a day with the Iraqi refugee and artist, now of Des Moines, surrounded by the things he loves.

Step into his mind through the swirls of deep hues he skillfully paints into a canvas.

See into his heart through his confident daughter, Bedor, and beaming wife, Sawsan, whose wheelchair is evidence of the hardship the family endured in their former life in Baghdad.

Sit at al-Obaidi’s table, sipping dark Turkish coffee that provides a striking contrast to his silver-white hair. Follow the deep-cut lines of his face and settle on his eyes — eyes that have seen some pain.

As a well-known painter in the Middle East, al-Obaidi is the former director of the National Museum of Modern Art in Baghdad and the national director for fine arts in Iraq.

The Museum of Modern Art was looted during the war, and a roadside bomb killed al-Obaidi’s son, Bader. Shrapnel from the bomb hit Sawsan, leaving her permanently disabled and partially blind.

After receiving a bullet in the mail with a threat attached, al-Obaidi and his family were forced to leave Baghdad and fled to Syria in 2006. Their neighbor drove the al-Obaidis on the 11-hour trip, and by luck, they passed through all the military checkpoints.

The al-Obaidis took only what they could carry. They left nearly everything else behind.

“[Iraq] is my country,” al-Obaidi said. “I lived in my country all my life. I have a family; I have a house in Iraq. I have a big farm in Iraq. My friends are in Iraq. Now I feel it’s very good for safe and quiet life in America, but I feel sometimes I am alone.”

Al-Obaidi’s daughter, Bedor, is a sophomore at Des Moines Area Community College, and she said her family was targeted because of her father’s prominent profession. Living in Iraq between 2006 and 2009 meant living in a period of sectarian violence between the Sunni and Shiites. Religious extremists targeted intellectuals and professionals who didn’t claim any one religion.

The al-Obaidis were given three days to vacate their home, and they were gone in two.

“It’s wonderful to have three days,” Bedor said, “because I have friends who get killed with no warning.”

After two years in Syria, the al-Obaidis finally gained refugee status from the United Nations. They traveled to Des Moines in 2008 through the sponsorship of the Lutheran Services in Iowa.

Only one of al-Obaidi’s paintings, a small depiction of an Arabic horse, made the trip.

The Lutheran Services placed the al-Obaidis, along with many other refugees, in tiny, cockroach-infested apartments.

“It was a small apartment,” al-Obaidi said, “and it’s not located in a good place at all.”

After about six months in the apartment, the al-Obaidis began renting a home in Windsor Heights.

Iraqi refugees complained about the conditions, and Lutheran Services eventually canceled the contracts at the apartment complex.

“The place was dangerous and nasty,” Bedor said. “We’re not poor; we’re not uneducated people.”

The living conditions didn’t stifle al-Obaidi’s creativity, however.

“Wherever you put me, anywhere or anyplace, I can paint,” al-Obaidi said. “It doesn’t matter where.”

In fact, it was in these tight spaces that he created an entire set of work for his first U.S. solo exhibition at Wesley House, the Methodist community center in Des Moines.

At the exhibition, al-Obaidi met Greta Anderson, of Ames, who became the first in the U.S. to collect his work. Friends and connections like Anderson helped al-Obaidi get his feet on the ground in the new country. They often contact Bedor, suggesting different galleries and exhibits for which al-Obaidi should apply.

“It’s difficult because I’m not young,” al-Obaidi said. “If I was younger than this age, it would be easier for me to go to the galleries and exhibits … but right now it’s quite difficult for me because I cannot go through the whole process and … travel to the galleries.”

Anderson is the social justice chair of the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Ames. She says the fellowship was designed for use as a gallery to exhibit artists chosen by the church’s Art Exhibit Committee.

“As soon as I met him and saw his work, it was my hope that we could bring him to Ames,” Anderson said.

Al-Obaidi’s exhibit, “Caravan of Exile,” was on display at the fellowship Aug. 30 to last Friday. His paintings were for sale at the gallery, with prices ranging from $250 to $3,000, a major drop from the $40,000 for which they once sold in Iraq.

These days, al-Obaidi spends his time caring for Sawsan, driving Bedor to her classes at DMACC and, of course, painting.

“The best job in all the world, in all the life,” al-Obaidi said, “the best job is the art.”

In his art, al-Obaidi uses copious amounts of paint, drenching his canvases in color and texture. Common subjects of his work include Iraqi women, birds and horses.

“I paint women and children and animals without men,” al-Obaidi said. “I don’t paint the men. He is terrible … the man make the war.”

“The woman is great in life … the woman is a mother, and we can interpret it as a home.”

Anderson said al-Obaidi’s paintings are deeply rooted in his culture and express themes of humanity.

“It’s about community and family,” Anderson said, “not about creed and the things that divide us.”

In Iraq, al-Obaidi’s paintings often alluded to poverty, politics and violence, but like everything else in his life, his work has changed.

“There is a lot of subject about the refugee and about the human being,” al-Obaidi said. “If you read the title of my show, [‘Caravan of Exile’], you can see the subject is new about my works.”

Even his use of color has transformed. In Baghdad, al-Obaidi chose shades of brown and gray. In Syria, he used brown and ocher.

“In America, I paint with red and violet,” al-Obaidi said. “I feel safer here than in my country.”

Bedor explained that the same colors that meant danger or violence in Iraq mean life in America.

“He’s tending to paint more for the life and be more optimistic and hopeful,” Bedor said.

Anderson said she was surprised by the optimism in al-Obaidi’s paintings.

“At first I was looking for a lot of themes of destruction, because I thought through the eyes of an American who wasn’t happy about the war,” Anderson said, “but I was surprised to see that many of his paintings are about … the restorative power of the imagination. They’re about dreams.”

On a rainy Sunday afternoon, al-Obaidi sits at home with his family and paints. The strokes of his brush seem to soothe everyone in the room, including him.

He says his favorite time to paint is in the middle of the night.

“The night is very quiet,” al-Obaidi said.

“And romantic,” added Sawsan with a smile.

After having a heart attack about three months ago, however, al-Obaidi tries to follow a better sleep schedule to aid in his recovery.

Sawsan and Bedor sit behind al-Obaidi, watching him work.

“He won’t start a painting unless my mom or I can see the process,” Bedor said.

Al-Obaidi has never had a studio; he prefers to work from home so he can be with his family, especially now that his wife depends on his care. He says he values the advice of his wife and daughter when it comes to his paintings.

“Thirty-five years I am sitting behind him while he paints,” Sawsan said smiling. “He is good man, he is good father, he is very good husband. I don’t feel he is my husband. I feel he is my best friend.”

Al-Obaidi is currently painting a piece for a Des Moines patron. In a setting typical of al-Obaidi’s work, women head to the market with their laughing, playing children.

“These people are very simple and very pure,” al-Obaidi said, gazing nostalgically at the canvas. “There aren’t a lot of problems in their life.”

“In Baghdad, we had a big farm, and I like people who work at the farm or in a small village.”

Sawsan suggests the name “Good morning, Iowa” for the piece, and so it is christened.

Although he misses his homeland, his family and his friends, al-Obaidi said he doesn’t plan to ever return to Iraq.

“I shall stay in America,” al-Obaidi said. “It is difficult now to live in Iraq. There are a lot of problems in Baghdad now. They didn’t choose the government. They’re afraid. They kill people.”

On the wall in the entrance of their home hangs al-Obaidi’s horse painting, a small reminder of the life the family left behind. The rich shades of red, violet and gold in his newer paintings jump out from nearly every wall in al-Obaidi’s art gallery of a living room. These colors outshine the pain the family continues to deal with every day and suggest a new life of hope.

Al-Obaidi said one day he may return to darker themes of suffering and pain.

“In the future, I try to paint paintings about … the problems and the violence in Iraq,” al-Obaidi said. “Now, I paint about the peace.”