- App Content

- App Content / News

- News

- News / Diversity

- News / Politics And Administration

- News / Politics And Administration / State

- News / State

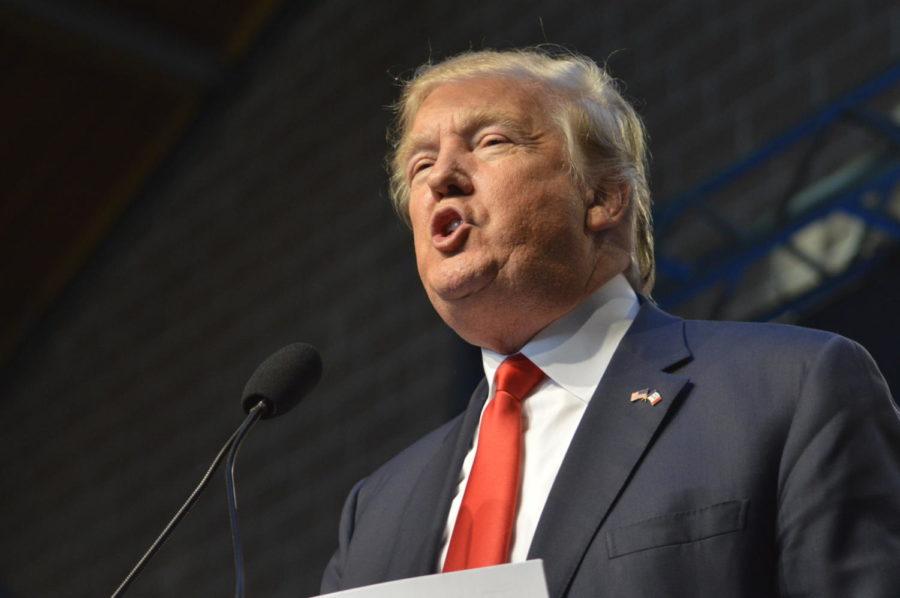

The new normal: How modern political rhetoric has changed the way minorities live in America

January 14, 2019

A border wall, trade protectionism and so-called “fake news” were not common focuses among politicians when Donald Trump started running for president, but now people can hardly go a day without hearing something on one of these topics.

Many of these policy goals — like the border wall — have been pushed for by a majority of members within the Republican Party, including state or local representatives who are not as affected by the implementation of the proposed wall.

However, the impacts of this rhetoric go beyond setting a focus for the party as it has fundamentally changed how some underprivileged and minority communities carry out their lives on a daily basis.

“The effects of the racist rhetoric of Donald Trump and the Republican party of Iowa are profound,” said Ashton Ayers, political director for the Iowa State College Democrats. “You have people in many different minority communities who feel unsafe, unwanted, mistrusted, and it creates a division among the population.”

Whether it is Gov. Kim Reynolds, Rep. Steve King or former representatives Rod Blum and David Young, Ayers said much of their language varies, but the general policy positions are consistent with one another.

“Donald Trump and everyone who is on his team is complicit,” Ayers said. “When you use language like Steve King utilizes, like Donald Trump utilizes; language that dehumanizes individuals; language that attacks people on the racial, cultural, ethnic or religious identity, you foster a division and belief that some people are less than others, and that they are worth less.”

Others, like Iowa State College Republicans Vice President Tim Gomendoza, said Trump is not the source of people’s sentiments towards immigrants or minorities, rather, it is caused by people being more open about their beliefs and feelings. Gomendoza said he believes people are going about their ideals, separate from what Trump would necessarily do.

“Trump is popular because he is a little more down-to-Earth,” Gomendoza said. “He is blunt, which is why I voted for him. He tells things like it is and doesn’t use euphemisms. This is where the culture pops up: People are tired of having to hide behind curtains and now they will say how they really feel.”

Gomendoza said he thinks Trump’s rhetoric is taken out of context, and as a minority himself, he feels there is no issue with the type of language used or if more candidates are using that type of rhetoric within their own campaigns.

While more people could take offense to the adoption of this rhetoric across the Republican party, Gomendoza said this is what people need to hear, and is the best approach if the president or other politicians want to do their jobs.

“In relation to the migrant caravan, we have a large influx of people who we don’t know, who we can’t really vet,” Gomendoza said. “The president’s job is to keep the American people safe so in regards to that incident alone I can definitely say Trump’s rhetoric is not racist or meant to be offensive, it is just dictation of what is happening.”

This type of speech, which some say was popularized by Donald Trump, has been blamed for a rise in hate crimes nationally, but Ayers and Gomendoza both agreed that this increase was present in the years before Trump. To Ayers, this means Trump is more a symptom of the culture than the cause of it.

Regardless, Ayers said there are still contributions Trump made to this culture that have impacted individuals down to the local level. In Iowa, for example, Ayers said he has seen an increase in targeting of minorities by police officers and the overall acceptance of racist or bigoted rhetoric. In addition, he said the rhetoric has “absolutely increased” racist and violent sentiments as well as racial division and the rise of white nationalism.

Senior Lecturer of Political Science Dirk Deam said correlating the rhetoric with the rise of racist tendencies is not as cut and dry as it sounds.

“The inference is fair, but it is hard to say this is all cause and effect,” Deam said. “When you give license to overt racist appeals or thinly veiled appeals, then it becomes harder to attack the moral notion that [hate crimes] are wrong … but I wouldn’t say it is a cause and effect”

If the Republican party were to disavow the problematic language of Trump or King, then Deam said it would be much easier for them to “sever the rhetoric from the behavior.”

During the Trump campaign and before the end of the Republican primary, many Republicans openly opposed Trump’s policy positions and the language he used to promote his policies. As this opposition slowed over time, Deam said it wasn’t due to the party suddenly agreeing with the platform. Instead, it was an electoral calculation.

“It’s not that they are racist or that they accept racism, but more that they are willing to tolerate apparent racism to the extent that it has no negative electoral effect,” Deam said. “Or to put it another way, trying to curtail it would have an adverse electoral effect, and they are afraid of that.”

Some members of minority groups have said they are the caught in the crosshairs while these calculations are taking place.

“I would say it has affected people very directly in our community — for queer people,” said Roslyn Gray, president of the Iowa State Pride Alliance.”Many of our community are white or middle class so we benefit from those privileges, but there are people within the community who have larger issues based on class or being a person of color.”

Gray said the rhetoric of Trump and people who use his style of speech emboldens others who have already had beliefs that were rooted in misconceptions or bigotry. However, Gray again pointed to this as a problem on the rise for years, not a problem directly correlated with Trump.

“We have had hate speech issues on campus before he was elected,” Gray said. “His rhetoric has been around for all this time, but our experiences of this rhetoric reach further back than his time within a position of power. If Trump was gone, the problems would still exist. It is a structural problem.”

How this structural question can be solved is one thing that Ben Whittington, president of Iowa State’s chapter of Turning Point USA, has struggled with answering as more people he knows have adapted their rhetoric to that of Trump’s.

Recalling a group chat he is a part of, Whittington said people he knew started speaking in ways he thought they never would. Whether it was white nationalist rhetoric, or people having issues with “white women dating black men,” he said he has noticed more of this speech as time went on, but bringing up his own opposition to those espousing it has been difficult as it often times gets brushed aside as “just jokes.”

“It was weird, it was weird,” Whittington said. “I don’t know if it is about me as a minority, or just that I am a principled conservative. I would always push back against that in the particular group. Only two people within a group of 30 to 40 people would push back against that stuff including myself, and I think Trump has something to do with people being open.”

While Whittington said Trump is in some ways responsible for this issue, some of that blame also is held by society and the structure in which there is an acceptance of potentially racist rhetoric. Through this structure and Trump using “dog whistle” political tactics, Whittington said Trump has been able to move the Republican party further to the right on issues of immigration and race relations.

“While I think the issue started before Trump, he saw that part of the Republican party, emphasized it and then capitalized on it,” Whittington said. “So he does still carry weight for its popularization.”

As this rhetoric has been popularized, Whittington said he has changed the way he and many other minorities function in their day-to-day lives. Instead of trusting people’s intentions, Whittington said he is more cautious. His experience within the group chat — people using racist language and calling it jokes — led him to second guess the intentions of anyone’s language use, and Whittington said this is now a problem for his generation as well.

“When my dad or my grandfather were growing up, you knew people who were racist because they wouldn’t let you in their schools or date their daughter, but now people are racist in not so open ways, and it makes me second guess everyone’s intentions,” Whittington said. “Because that doubt is there, myself and other minorities start to question every privileged persons actions.”