Waterloo, Cedar Falls area named No. 1 in U.S. for racial disparities

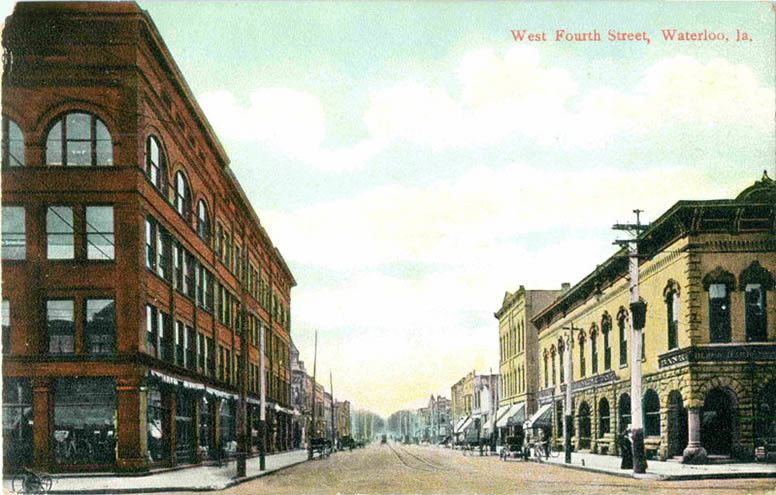

A postcard depicting West Fourth Street in Waterloo, Iowa in 1910.

November 27, 2018

The Waterloo and Cedar Falls metro areas were rated the highest in the United States for racial disparity in an index based on eight socioeconomic measures in U.S. metro areas.

Waterloo and Cedar Falls have a black population of 12,085. While the area’s white unemployment rate amounts to 4.4 percent, nearly 1 percent higher than the national unemployment rate, the black unemployment rate is 23.9 percent.

A similar disparity is seen in homeownership rates, with the area’s white population amounting to 73.2 percent, while black homeownership rates come to 32.8 percent.

The cities that cracked the top 15 in the index, created by 24/7 Wall St., are historically plagued with an immense amount of residential segregation and discriminatory lending, zoning and renting practices.

A brief look at black experiences and histories in the Cedar Falls and Waterloo area, however, may lend a better understanding as to how such deep disparities continue to persist in the state of Iowa.

On a Friday night in 1968, East High School Trojans of Waterloo, Iowa started off their football season. The game was played at West High School’s Wallace Stadium, an all-white school on the predominately white side of town. East High had no stadium to house it’s opponent.

During halftime, police officers attempted to arrest a young black man outside the stadium. Students took notice and poured around the incident. Disorder erupted. Officers used mace and clubs in an effort to control the students. After the game’s end, a fire was started at a lumber company that engulfed its mill and nearby homes. At East High, gasoline and lit matches were thrown into classroom windows.

According to an article from the State Historical Society of Iowa and written by historian Katy Schumaker, “The next day, the streets were deserted except for hundreds of National Guardsmen who patrolled the city’s east side on foot with bayonets and in Jeeps and trucks stocked with smoke bombs.”

In an interview with the Waterloo Courrier in 1968, Waterloo East High superintendent George Hohl claimed that the ‘New Left’ movement across the country was responsible for the unrest in Waterloo. The local newspaper also reported that the police department had identified the protesters as “militants and agitators.”

Katy Swalwell, associate professor in the School of Education at Iowa State, said that while Iowa courts ruled against segregation early in our nation’s history, results were not successful.

“While Iowa did rule against discrimination and passed civil rights legislation in the 19th century, it would take decades to successfully enforce those laws, which communicates very strongly to white people that the legislation was largely symbolic,” Swalwell said.

The 1968 student disorder in Waterloo gave rise to a coalition of residents, white and black, united around the need for further reform. In the following years, dismantling racial discrimination in the school was a primary concern of the community — and it was pushed by student activism.

It wasn’t until 1973, 105 years after Iowa Supreme Court ruled against segregation in public schools, that the Waterloo school board voted 4-to-3 to finally codify desegregation in school board policy.

But students in Waterloo were less interested in desegregation than they were in implementing what they saw as a new standard of race relations between school administrators, teachers, and students.

Waterloo East students demanded that teachers who did not feel they could treat black students as equals to white students resign and that a relevant education and a course in black history be implemented.

The demands that Waterloo’s East High students would make in 1968 are still relevant today.

“How demands from 50 plus years ago still aren’t being met should infuriate us to action … especially those of us who have benefited from these systems for so long,” Swalwell said.

Beyond the lacking education on Iowa’s black histories, there are a number of barriers black students face in Iowa. Public schools are riddled with achievement gaps that leave minorities, particularly African-Americans, far behind white students.

Statewide, only 49 percept of black fourth-graders are proficient in reading, compared to the 80 percent of white students, according to exams from the National Assessment of Education Progress.

“It is also to reiterate for white readers that the systems, traditions and practices they may trust to work for them have not worked, often by design, for communities of color,” Swalwell said.