- News

- News / Academics

- News / Diversity

- News / Politics And Administration

- News / Politics And Administration / State

- News / State

Reynolds signs bill to restrict divisive concepts from diversity training, school curriculum

New legislation bans concepts that label America and Iowa as “systemically racist,” and it is intended to prevent “racial and sex scapegoating.”

June 9, 2021

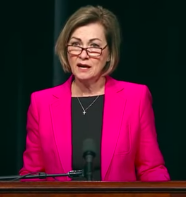

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a bill prohibiting specific “divisive” concepts from diversity training and school curriculum, such as America and Iowa being systemically racist.

The bill does not specifically list concepts like critical race theory or the 1619 Project, but both have been subjected to criticism. Reynolds said critical race theory would fall under the ban.

“Critical race theory is about labels and stereotypes, not education,” Reynolds said in a statement. “It teaches kids that we should judge others based on race, gender or sexual identity rather than the content of someone’s character. I am proud to have worked with the legislature to promote learning, not discriminatory indoctrination.”

The 1619 Project places the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the core of American history, according to the 1619 Project’s website. critical race theory is decades old and grew out of critical legal studies. The theory is not a form of training but is instead a practice of critically examining and questioning the roles race and racism play in society that emerged in the legal academy and has spread to other fields of academic study, according to the American Bar Association.

Monic Behnken is an attorney, member of the Ames School Board and an associate professor of sociology; her views are her own and not representative of Iowa State. Behnken said critical race theory was founded out of the idea that racial inequalities haven’t improved since the theory was founded.

Iowa joins a handful of other red states in creating legislation to combat an “anti-American” rhetoric in workforce training and public education, mirroring an executive order that passed at the end of the Trump administration. Behnken said it is difficult to have conversations about the impacts of these laws because they are inaccurate in portraying critical race theory.

“I look at these laws in total and am just confused,” Behnken said. “I am not quite sure what has been outlawed or why it is being called critical race theory because I don’t see critical race theory reflected in the specific things that are now illegal.”

Behnken said there are some components of critical race theory that may be taught at the undergraduate level, but critical race theory is a high-level and complex area of academic study that mainly exists at the graduate level.

In February, Ames Community School District received similar criticism from Republican legislators about Black Lives Matter at School Week. The program is unaffiliated with the national organization but is intended to teach about Black experiences beyond slavery. The program is designed to be transformative for all students, regardless of race.

What has been taught has caught the attention of the Iowa Legislature. Republican legislators are said to have received calls, emails and texts from concerned parents about the “indoctrination” of their children in the K-12 public school system.

Behnken said the law appears to be a list of grievances against racial inquiry, and items in the bill are being labeled as critical race theory even though the descriptions do not actually match the theory.

“The concern isn’t necessarily about critical race theory, whether you can teach it, whether you can’t, whether you can’t teach these collections of grievances, but really rather ask Americans, are we free to ask questions of our government?” Behnken said.

When asked by reporters if Iowa educators would be allowed to teach students the story of Black Hawk if the bill should pass, Reynolds said his story should still be included in educational discourse but under conditions.

“As long as it is balanced and we are giving both sides, I think it is part of history and they should be able to teach that,” Reynolds said. “It has to be balanced and make sure we are having a conversation, and we are educating children, not indoctrinating, and actually giving them the chance to learn and to make their own decisions.”

Sebastian Braun, director of the American Indian studies program and associate professor of world languages and cultures at Iowa State, said Native Americans are often excluded or misrepresented in American history.

Black Hawk was a war leader for the Sauk tribe and fought with the British against Anglo settlement, resulting in disproportionate deaths of Indigenous people, according to History.com. Specifically relating to Black Hawk, Braun said few students come to his class informed about Black Hawk’s story or with any prior knowledge about indigenous people and cultures at all.

“If anything is taught, it is definitely the case that students don’t have a good understanding of what happened,” Braun said. “I take great care, if you want, to ‘balance’ things out.”

When Braun was asked if there are any misconceptions taught in American education about the biography of Sauk warrior Black Hawk, Braun laughs.

“Is anything even taught in the American education system? That would be my first question,” Braun said.

Behnken agrees history should be taught in a balanced manner, but Behnken said teachers already operate in that way. Looking back on her own experiences in the public school system, Behnken said her education actually wasn’t balanced.

HF 802 doesn’t limit a specific curriculum but instead prohibits assigning status and privileges to a specific race or sex and assigning bias based on race or sex; it is referred to as “race or sex scapegoating.” The bill also prohibits academic concepts that present America and the state of Iowa as systemically racist or sexist.

“Critical race theory has been around for decades; it is not new, but this conversation is,” Behnken said. “This conversation exists in a context that our country has lived through this socio-political uprising over the past summer that has been rolling for decades, and what I am seeing across the country are really attempts to ban conversations that people want to have about how our world looks.”

In Braun’s course Americans of Iowa, Braun kicks off his class by asking his students what they know about Iowa’s history, which tends to be very little.

“What the American education system is doing right now is presenting American history, and American history is defined as basically white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant,” Braun said.

With the exception of genocide, there are always positive and negative consequences to anything. Braun said he is hired to not present his opinion, and calls for balanced discussion are usually driven from a political perspective. For example, when Braun teaches about boarding schools, he said there are always multiple perspectives.

Positive consequences, while not intended, include cross networks among tribes and enabling people to communicate in one language to build organizations and political resistance. Education allows individuals to participate as far as they are allowed in the American democratic process. Negative consequences include trauma, prohibition of languages and cultures, overworking and brainwashing.

“When I teach something like that, I think students should understand both the positive and negative consequences,” Braun said. “What I try to teach students is not what I feel about it. What I try to teach students is how they can then look at that data and make up their own mind.”

Bran said because it is impossible to measure culture and history in a quantitative method, people automatically assume the information isn’t factual.

Braun has received an array of feedback from students of different backgrounds. Some accuse him of being an apologist for the treatment of Native people, while others come to him and defend the reasoning behind assimilation. Braun said these perspectives come from political assessments people have already made.

Braun works to present data in a balanced manner, and he does not address the political opinions unless they are brought up by a student. When a political discussion is brought up, Braun leaves it to his students to handle balancing the differing opinions.

Questions of enforcing the law for training and curriculum that break restrictions remain unanswered. Behnken said the number one job as a teacher is to create an environment in which all students are able to learn. In her 12 years of teaching, Behnken has had conversations with students where they felt unheard, and she was able to address the student’s concerns and resolve the misunderstanding. Now, Behnken has concerns she could be subject to legal ramifications if a similar situation occurred.

Behnken is the instructor for the summer course Criminal and Deviant Behavior. Because of the lack of clarity in the law, Behnken is unsure if she will need to rerecord lectures, require her students to buy new textbooks or even cancel the class.

When teaching Iowa’s history, Braun said the foundation of the state flows from treaties. Every square inch of Iowa is treaty land, and the Iowa people were annihilated shortly after Euro-American settlement. In the 1830s, tribes ceded their land through treaty and purchase. Now, Mesquakie settlement is the only remaining reservation in Iowa, home to the Fox and Sauk tribe.

“We cannot get a true understanding of Iowa history if we don’t understand those processes, what they meant and mean today, and that is what’s not being taught,” Braun said.

Braun visits schools like the Des Moines public school to try and incorporate Native history into curricula.

“I was hired to teach factual accounts of history, of cultures, of societies,” Braun said. “Now, if somebody asks me to do this in a balanced manner, I honestly don’t quite know what that means because what they would be asking is to teach from a political perspective. And this is exactly what I am hired to not do; I am not hired to bring politics into the classroom.”

Behnken is the mother of two children and is beginning to have conversations about college.

“As a parent, do I want to send my child to a school in a state that has told me, ‘We will get legislative-approved education and nothing more’?” Behnken said. “I have been a student half my life, and I have been exposed to many theories, concepts and ideas. Some of them have been useful and I kept them, and some of them have not and I have discarded them, but I have had the opportunity to consider them, and that is what I want for my children.”