The population of women majoring in engineering at Iowa State is small compared to men and can often face adversity surrounding gender.

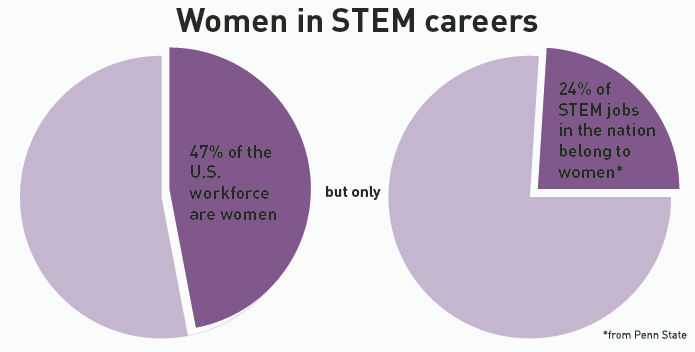

WiSTEM, Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, was initially created to shed light on females in predominantly male careers. At Iowa State, the engineering program has an estimated 7,807 students enrolled, with enrollment data showing about 82% of students being male.

Avary Rech, a sophomore in aerospace engineering, always knew she would go into STEM. Rech said she is thankful for her teachers who encouraged her to pursue her love of math and science, and her love for airplanes. Growing up next to an Air Force base, Rech constantly watched planes, which led her to choose aerospace engineering as her major.

Rech said that not only her male classmates treat her differently, but also professors and teaching assistants, especially in classes where she is the only female student.

“I had chemistry with 20 other guys, and it was just me,” Rech said. “For the longest time I was the only one who [the professor] ever called on. I was the only one he knew by name. If nobody else was talking, he would go straight to me and ask me questions directly every single time. He singled me out.”

Rech said that in her classes, she feels pressure to excel solely because of her gender.

“There’s a weird amount of pressure to excel and do well in your classes because if you fail, everybody who’s already judging you, like the men in the class, are like, ‘Oh, she failed not because she didn’t study, not because she didn’t know the material, not because she had a bad day, it’s because she just isn’t smart enough to be here,’” Rech said.

Amelia Schroeder, a freshman in software engineering, said there is not a day when she does not feel the need to prove herself within her major.

“Being a woman in engineering, there’s just something different about it,” Schroeder said. “You’re constantly surrounded by people who don’t think you’re good at what you’re doing.”

Schroeder said throughout her first year, she has received several derogatory comments surrounding her gender, several of which occurred when she was simply attending class.

“One time, I brought a coffee to my physics class,” Schroeder said. “A guy was like, ‘How is that going to help you learn better? How many calories are even in that? Oh, sorry, I didn’t mean to trigger anything.’ [Meanwhile] I’m just sitting here, and he’s asking me this, and this guy hasn’t been to class in two weeks.”

Schroeder gave examples of group projects within her courses and major where she feels the male students do not think she is qualified to do the work.

“I was in a group project with this guy, and I was like, let’s divide it up equally, and we’ll try our best,” Schroeder said. “And he said, don’t worry, I know you aren’t good at this, so just sit there. The same guy also took credit for my solutions and my ideas.”

Schroeder said she initially chose to major in engineering because she wanted to do various things revolving around design and creativity. Before coming to Iowa State, Schroeder knew there would be a small group of women in her classes, but she did not anticipate the treatment she would face.

Rachel Fiedler, a freshman in mechanical engineering, always knew she wanted to do something surrounding STEM because of the science aspect of it. Fiedler said she always found engineering extremely interesting.

Fiedler also said she feels a mass amount of pressure to succeed in her major simply because her gender is the minority.

“You can’t just do well; you have to do extremely well. If a guy gets a B, you have to get an A just in order to prove [you] belong here, [that you are] meant to be here,” Fiedler said. “You constantly feel like you’re needing to prove yourself and explain yourself.”

Emily Warring, a junior in aerospace engineering, chose this major for her love of math, science and space. Warring grew up in a small town in Minnesota where there were not many engineers surrounding her, so she wanted to combine everything she was passionate about into a career.

Warring said one of the most complex parts of being a woman in engineering is the small number of women in her classes.

“I can easily count the amount of women in them,” Warring said. “You look around, and all you see are men. There were 10 girls in my first semester aerospace engineering class. You’re only becoming friends with the other 10 women when there’s another 200 people in your class.”

With the ratio from men to women showing a significant difference, Schroeder said if women want a support system or help to do the course work, they most likely will have to talk to a man, even at the chance of offending their male peers.

“A lot of the guys that I know in my classes, they make dumb, ridiculous jokes,” Schroeder said. “And so, if you want to continue with that support system or friendship, you have to let that slide, and it’s so difficult for me morally.”

Fiedler said she is constantly trying to blend in and not draw attention to herself because she already feels out of place.

“I feel like there is definitely a pressure to dress stereotypically like an engineer. So wearing skirts or something makes me feel really weird,” Fiedler said. “Even if I really liked the outfit, I feel so out of place in this super feminine outfit with a bunch of men.”

Warring said she never answers questions in class because she does not want to get an answer wrong and potentially be considered “stupid.”

Fiedler also said that if girls get an answer wrong in class, they fear they are reinforcing the stigma and perceptions that men in the class already have of them, that they cannot do this.

Warring said she realized she would be treated differently within the first week of the fall semester. Warring was in a lab group during the fall, and she said she felt that the men in her group did not respect her until she proved herself.

For a class assignment, Warring’s group was tasked with dropping an egg without cracking it. She suggested putting a parachute on the egg to slow it down and help it survive the landing. Warring said her male group members practiced dropping it without a parachute, which almost broke the egg.

“Then they’re like, we need a parachute,” Warring said. “It dawned on me then. It did get a little bit better with that group once they finally realized I knew my stuff, but you have to earn their respect and you shouldn’t have to, because I respected all of their opinions. But I didn’t get the same treatment back.”

In Fiedler’s first semester of school, she was one of two girls in her engineering class. At the end of the semester, Fiedler said she and the other female student presented their final project, which included getting feedback from their peers.

“They were just nitpicking the most ridiculous stuff, [like] ‘You were just standing up there weirdly; we couldn’t hear you, talk louder; why did you stand there? It just looked really unbalanced, you looked really nervous,’ and that was really off-putting. It was just like the most absurd stuff,” Fiedler said. “Other people’s projects weren’t even done. We were the first group to go, and they did the same thing. It wasn’t constructive criticism, and it wasn’t about the content we were presenting.”

Rech said that her gender is irrelevant, and when it gets brought up consistently, she feels singled out, and like people are making it a big deal.

Schroeder said she wants men in her engineering classes to think about what they say and how they would take it if the roles were reversed.

“Just assume that everybody deserves to be there,” Rech said. “These are hard classes everybody’s taking. Everybody has had to work to earn their spot and is more than capable of being here and doing the work. Everybody deserves to be considered and respected in that environment.”

Warring made a similar statement regarding how she felt when men talked down to her in her classes.

“Would you speak to your sister or your mom this way? Would you speak to women that are closely related to you in this demeaning way?” Warring said.

Schroeder said she feels uncomfortable calling out this behavior out of fear of being labeled as an “emotionally unstable woman.”

“You cannot make a big deal out of it because you will be stereotyped as just an angry or over-emotional woman,” Schroeder said.

Rech said it sometimes feels like men in aerospace engineering think women owe them something, or that they have to act a certain way at all times.

“I feel like men sometimes expect that women owe them something like whether it’s a calm demeanor or like respect,” Rech said.

Warring said men are surprised in her classes when she can use tools and work on an assignment just like them.

“In my aerospace group last semester, we built an aircraft, and I knew how to use every single tool, and that was surprising [to male group members],” Warring said.

Schroeder, Fiedler, Rech and Warring all said they do not want to be on a diversity checklist; they want to be successful in their field because they earned it.

“I don’t want to deal with the pressure of having to be a role model and be an inspiration for other people’s daughters,” Rech said. “I’m trying to get my education, literally like everybody else.”

Schroeder, Fiedler, Rech and Warring also said they receive unfair treatment from the men in their classes at least twice a week.

“There’s always something ensuring that you’re just a stereotype,” Schroeder said.

Schroeder said it is difficult to come up with a solution because the problem is widespread.

“You don’t know where to start; you don’t know where to begin,” Schroeder said. “Do you start with making the guys think or act differently? Or do you start with trying to get more women in STEM, do you try and bring up this behavior? There’s just so much to think about and do.”

Warring said she wants other women in STEM to know they are not alone and that she understands what they might be going through. Warring said she knows she is smart, but in class, it feels like she is not.

“It’s further proof in my mind of, like, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t be here,’” Warring said. “I have to fight so hard to remind myself that I was accepted here. I want everybody else to know that they’re worth it. They are here for a reason. It’s hard, but there’s so many resources and people you can lean on that have gone through similar things or are going through something now.”

Schroeder said she encourages women considering going into STEM to do it and that she believes anyone can be capable of being in STEM.

“I feel like every single woman I’ve ever met or known could go into STEM, like you can do that,” Schroeder said. “But it’s because people have made them feel not smart enough and not good enough to go into a STEM major, so they don’t.”