Kenneth Quinn, former United States Ambassador to Cambodia and 20-year president of the World Food Prize Foundation was welcomed to Iowa State University on Monday to share his experiences in a lecture titled “Vietnam 50 Years Later: Insurgency, Genocide, Dissent & Peace Through Agriculture.”

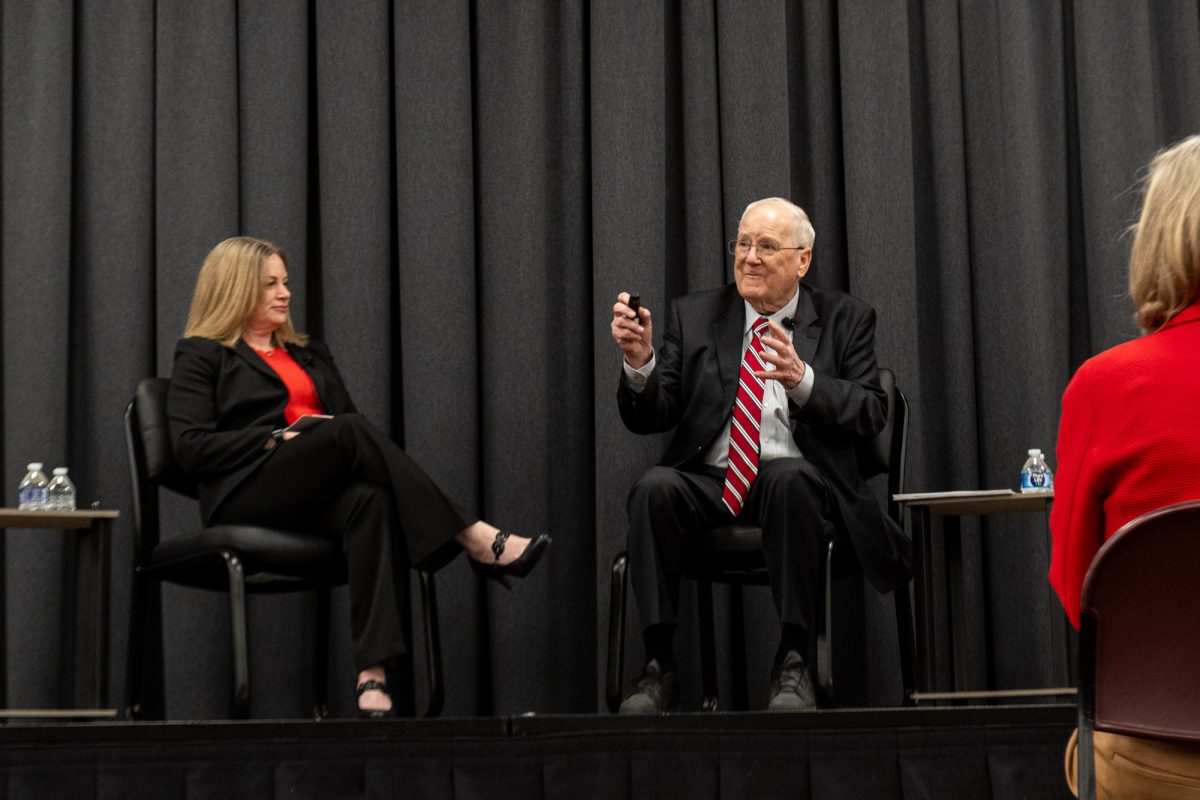

The conversation with Quinn was held in the Sun Room of the Memorial Union starting at 6 p.m., with moderator Amy J. Rutenberg, associate professor of history. It concluded with catered refreshments and time for audience members to inquire Quinn with questions.

Quinn worked for the Department of State for 32 years, serving in positions as a member of the National Security Council staff at the White House and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State. During this career, Quinn, who is fluent in Vietnamese, acted as a translator for President Gerald Ford.

For his achievements on aerial operations assigned to an advisory team with the Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s Civil Operations and Rural Development and Support (MACV/CORDS) in 1970, Quinn was presented with the U.S. Army Air Medal for his service, being the only civilian to receive this honor during the Vietnam War.

Quinn has Iowan roots; though he was born in New York City, his family soon moved to the Midwest when Quinn’s father took a new job, and he started high school out in Dubuque, Iowa.

“It’s like transplanted rice,” Quinn said. “I was first started in New York but picked up and replanted in Iowa where my roots took hold.”

Throughout the lecture, Quinn shared about his journey as a distinguished diplomat and what his life looked like in Saigon 50 years ago as a Foreign Service Officer.

“I’d meet Vietnamese [people], and had women implore me, ‘Please take my child out with you when you [leave]. Take my little child,’” Quinn recounted.

Reflecting on his service, he described a particularly memorable moment of his time spent in Vietnam. During his service at a dire time in the war, Quinn implored fellow U.S. government officials about the state of evacuation for refugees, raising his concerns.

“The country’s coming apart… I said to them… maybe when the last days as everything’s falling apart, we can save some people,” Quinn said.

They decided to take matters into their own hands and worked to organize safe houses in order to get people out of a nation in crisis, despite putting their jobs on the line.

“There comes a moment where you have to decide if you don’t do something and a bad thing happens, can you live with yourself? If you see a problem, see an issue… and you have to be willing to put your career at risk,” Quinn said.