Two’s a crowd: Multiple women on ballot lowers electability, experiment shows

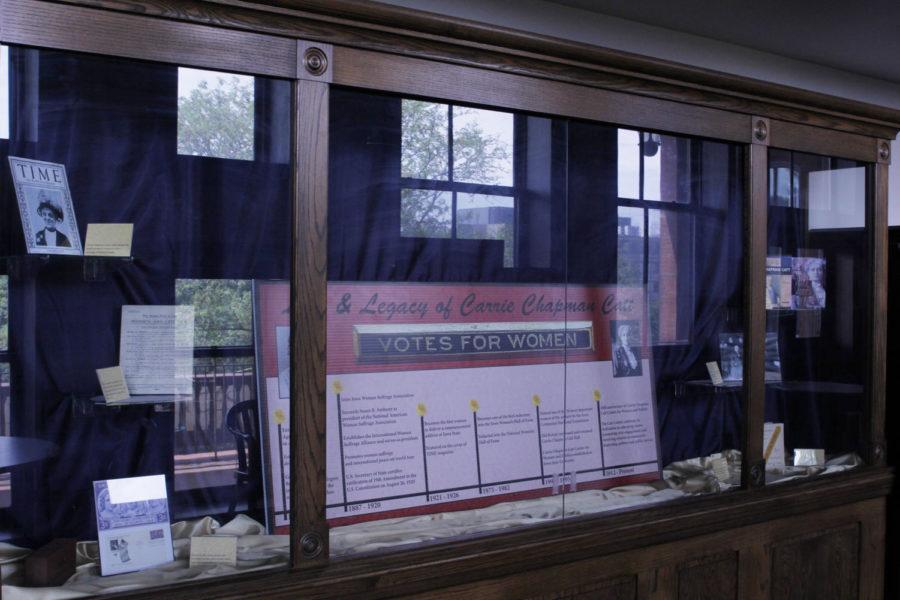

Photo: Jonathan Krueger/Iowa State Daily

The Catt Center located on the third floor helps women who are trying to make it into any political office.

August 30, 2018

When a single woman is running for political office, the single candidate does just as well as a male counterpart, according to a recent experiment by researchers at Iowa State.

The experiment, titled “Two’s a Crowd: Women Candidates in Concurrent Elections,” also found down-ballot, or lower office, female candidates tend to experience a significant drop in votes when another female candidate runs for a higher position in the same election cycle.

Lead author Tessa Ditonto and her co-author David Andersen, both assistant professors of political science, conducted two experiments centered around women on the ballot.

“Most research on American elections looks at each independent campaign as if it was in isolation, and we wanted to look at a more realistic scenario, taking into account the broader political environment,” Andersen said. “It’s important, especially today, because more women than ever are running for political office, and it’s probably not accurate to pretend like that doesn’t matter.”

Ditonto and Andersen used a series of campaign simulations to gather data on voting habits. The participants in the experiments answered a series of questions about their partisanship, ideologies, stance on political issues and demographics. After answering questions, the subjects sat through a mock campaign for many governmental positions and were shown information about all the candidates on the ballot.

The researchers could systematically vary the gender of the candidates that the participants could vote for. After the subjects had completed the campaign, they answered another series of questions about what they learned, what they thought about each candidate, and which candidates they would vote for.

“Because we can vary the gender of candidates, we can see whether how many women they saw at one time affects how they learn during the campaign and whether it affects what they say about the candidates after the campaign,” Ditonto said.

The results of the experiments pointed to one strong conclusion: when there was a single woman running for an office, that candidate did just as well as her male counterpart.

When more women were added to the ballot, however, those who were running lower on the ballot did worse. People disliked and were less likely to vote for the down-ballot woman if there was an upper-ballot woman also running. Andersen and Ditonto hypothesize that this result has to do with female stereotypes.

“Female candidates are often seen as less competent, less qualified and they have to address these stereotypes to the voters,” Andersen said.

Higher office candidates tend to have higher budgets for their campaigns, and the populace gets to know that candidate better. With the down-ballot offices, there is less of a budget and less is known about the candidate, so the voters form opinions based on stereotypes; women being quiet and submissive, and men being decisive and dominant, according to the experiment.

The strength and consistency of the findings surprised the researchers.

“The fact that we found essentially the same things across two different experiments and that it was such a striking series of findings, we were a little surprised by that,” Ditonto said. “Theoretically, it made sense that we would find something, but it was more robust that we anticipated.”

The concept of women being negatively affected by stereotypes is not new.

Kelley Winfrey, interim director of the Carrie Chapman Catt Center, has seen a significant gap between males and females participating in political affairs both on the ballot and on campus.

“We know that women are less likely to take classes in political science or government, they are less likely to be involved in political organizations when they are on campus, and are less likely to be involved in political discussion,” Winfrey said.

At the college level, women are not as included in the conversation surrounding the political climate, for a variety of reasons, and that exclusion may result in a hesitancy to pursue a political career, Winfrey said.

Ditonto, Andersen and Winfrey all agree on the most logical solution to lack of gender diversity in politics: Get women on the ballot. As more and more females are listed on ballots, the thought of women in politics becomes more normalized, and the stereotype of men being the only gender suitable for leadership will begin to break down.

“When we see women candidates running against each other, we start thinking about the topic of gender. Similarly, all the stories talking about the record number of female candidates are making more people think about gender, and that could strengthen the effect,” Andersen said.

Ditonto and Andersen plan to compare their simulation data with the results of the 2018 election.