- App Content

- App Content / News

- News

- News / Nation

- News / Politics And Administration

- News / Politics And Administration / State

Trade negotiations fail as deadline closes in: trade war ensues

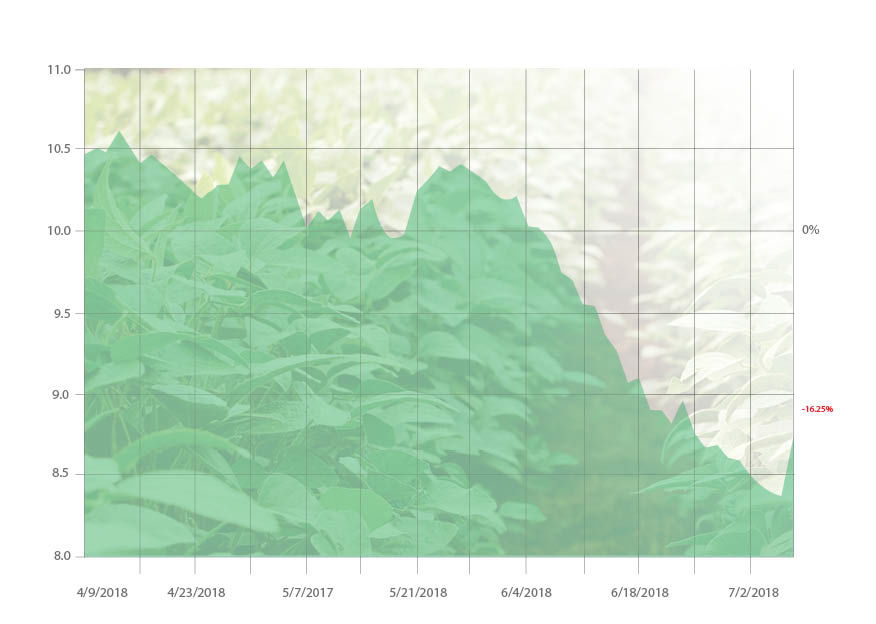

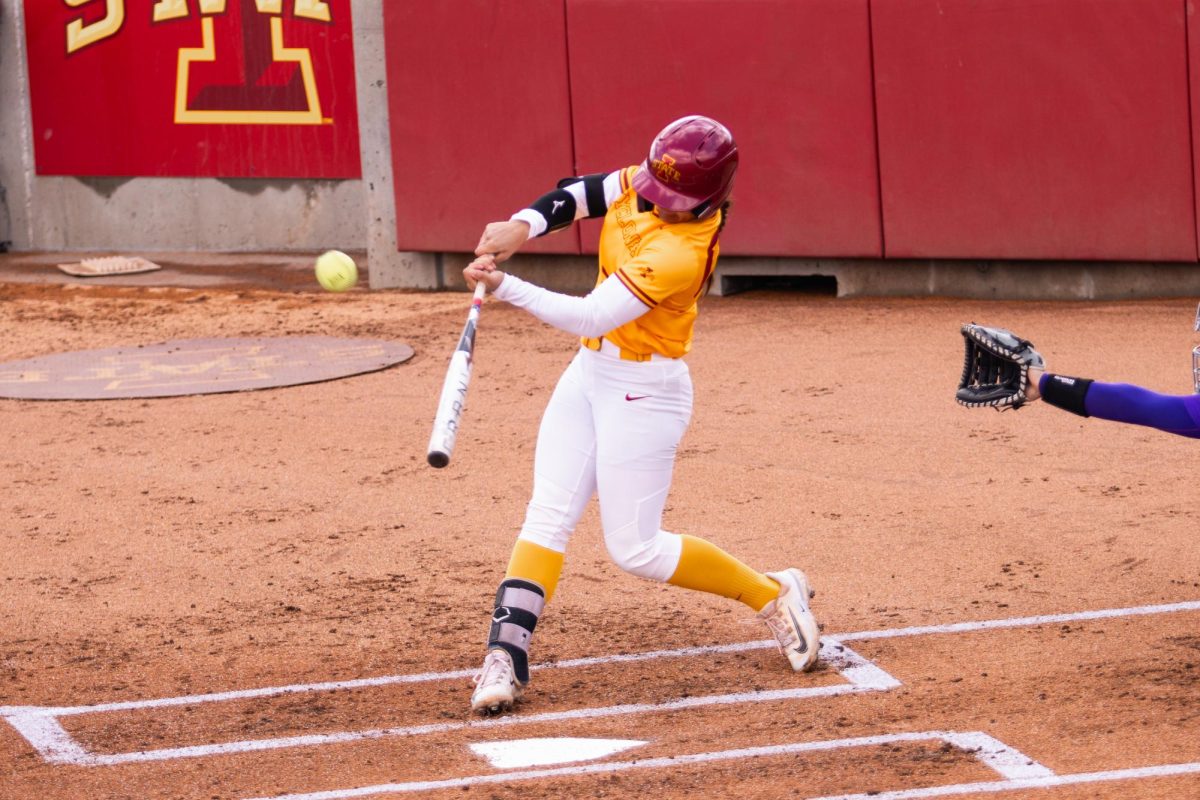

Photo: Emily Blobaum/ISD Graph: Courtesy of Business Insider

The graph represents soybean prices in the United States over the last three months in price per bushel.

July 8, 2018

Crop prices, the Iowa economy and global markets face massive uncertainty as trade negotiations between China and the United States have reached their deadline, kicking off a trade war that currently has no end in sight.

The United States has put a 25 percent tariff on $34 billion of goods from China because of a perceived trade inequity between the two nations. Tariffs are essentially taxes on goods sold or manufactured from another country, and, as a result, tariffs make those goods more expensive and decreasing consumer demand.

President Donald Trump has also implemented aluminum and steel tariffs on Canada, the European Union and Mexico, a move that could have ripple effects on trade in other areas.

As a result, Canada imposed retaliatory tariffs on over 80 U.S. goods worth CAD$ 16.6 billion and, Mexico imposed $3 billion in tariffs on pork, apples, potatoes, bourbon and various cheeses.

Chad Hart, associate professor of economics for the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Iowa State, said the talk of tariffs began in January of this year, and since then, the markets have been preparing for potential damages.

“Since the talks started, especially in the last month or so, we have seen soybean prices drop as low as $2.00 from where they were,” Hart said.

These price drops are a result of the Chinese, Canadian and Mexican governments matching any and all tariffs the United States implements on each country respectively.

However, following the most recent tariffs, Hart said, soybean prices have actually gone up 20 cents. This can be explained by much of the market uncertainty that has been built up over the last month.

“Originally, Trump had talked about tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese goods but it turned out to be closer to $35 billion,” Hart said. “The other $15 billion will likely come at a later date, probably within the next month.”

This slower implementation process might have been what the market needed to gain some confidence back, but Hart said the impacts might have been slightly overstated to begin with.

“The market assessed itself and said, ‘maybe we pushed prices too far down,’” Hart said. “Even trade economists who have been studying this very closely did not expect the prices to drop as much as they did earlier in the month. It seems there may have been an over-reaction, at least partially.”

The $50 billion president Trump has committed to is not the full extent of what could come, in fact, Trump has proposed placing tariffs on as much as $500 billion in Chinese goods — nearly the entire sum of Chinese goods sold in the U.S.

“If we see the full $500 billion, we are talking major ramifications,” Hart said. “Global consumers —not just U.S. and Chinese consumers — will feel the impacts. Basically all of the global markets, because you are talking about the two largest economies in the world, hitting each other with trade taxes that will disrupt trade flows throughout the globe.That will mean higher prices for consumers around the globe but also lower prices for producers.”

Part of this global trade war, Mexico, a close agricultural trading partner and number one importer of U.S. corn and pork, could seriously impact the midwest agricultural markets.

While Mexico’s tariffs target just 1 percent of exports from the United States it is about who and where those tariffs are targeted at.

According to CNN money, 25 percent of U.S. pork exports went to Mexico last year and that has some farmers reeling.

“A 20% tariff eliminates our ability to compete effectively in Mexico,” said Jim Heimerl, president of the National Pork Producers Council and a pork producer from Johnstown, Ohio in an interview with CNN Money. “This is devastating to my family and pork producing families across the United States.”

The tariffs imposed on Canada and Mexico are supposed to be forbidden under the North American Free Trade Agreement, but Trump, a major critic of NAFTA, would like to renegotiate much of the deal.

Both Canada and Mexico have said they would retaliate an equal amount for each new tariff put in place, effectively starting a trade war.

“We are in the trade war now,” Hart said.

While Trump has said trade wars, “are easy to win,” Hart said he is “not in the camp that trade wars are winnable.”

“A lot of these negative impacts happen very quickly,” Hart said. “If you are looking for positive impacts, those don’t typically happen until much further down the line. The goal is for trade rules to be more equitable.”

Counter to this goal, China, Mexico and Canada’s motivations for targeting ag related products from the U.S. could be both political and economic, Hart said.

“By area, [soybeans] are the number one largest crop in the U.S., and China is the number one consumer of soybeans,” Hart said.

It isn’t just about the crops, however, China could be targeting the people of the midwest.

“$20-to-25 billion of U.S. exports to China are ag related,” Hart said. “For China to have the largest political impact with their tariffs, targeting the rural economies which typically lean conservatively or who might have voted for Trump is their best option.”

With soybean and corn prices already on the decline for the last four years in addition to the last month seeing a 20 percent decline in crop values alone, midwest farmers could see growing economic pressure.

According to recent data from the US Department of Agriculture, 4.39 billion bushels of soybeans were produced in 2017 and a quarter of that harvest is still stockpiled waiting to be sold. Taking into account last months price decline, those soybeans currently stockpiled lost $8 billion in value.

While it may be reduced, consumption of U.S. grown soybeans overseas will not be completely eliminated.

“China gets their soybeans from many other countries like Brazil, but the sheer amount of soybeans produced in the U.S. means China will still have to get some from the U.S.,” Hart said.