Iowa State doctoral student turns tragedy into possibility with ALS research

January 18, 2018

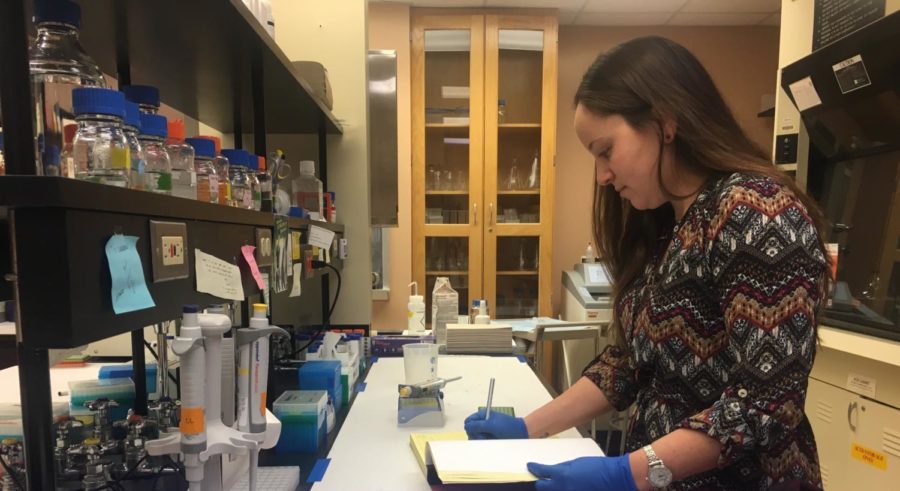

Lauren Laboissonniere was 13 when her grandfather died from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Now that she is a doctoral student, the disease coined Lou Gehrig’s disease is the focus of her research.

Laboissonniere is studying cell populations in mouse models of Lou Gehrig’s disease. ALS is a neurodegenerative disorder where the motor neurons — the cells that control movement — begin to degenerate. In the beginning stages, symptoms like muscle stiffness and tingling are present.

As the disease progresses, it can weaken the diaphragm and make things like breathing difficult. ALS is fatal, has no cure and very few treatments.

“It left a really lasting impression on me,” Laboissonniere said. “There’s no great treatment option for people with the disease. Then I came to Iowa State.”

ALS — like many neurodegenerative diseases — is progressive, meaning that when the disease first sets in, there are little to no noticeable symptoms, and over time it becomes more serious, painful and even fatal. Most neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease have few treatment options, if any. Unfortunately, ALS is no different in this respect.

At 13 years old, Laboissonniere hadn’t seen illness that couldn’t be fought. Despite her father having varying forms of cancer, he had always been treated, and the cancer would be gone.

“When I was growing up it was like you get sick, you go to the doctor, you get better,” Laboissonniere said. “My father has had different types of cancer all my life, but he would go to the doctor and he would get better. So even cancer to me wasn’t, like, a big deal.”

Laboissonniere said that when her grandfather was diagnosed with ALS, she had never encountered a disease that couldn’t be treated. So when her mother — who was a nurse — told her that her grandfather wasn’t going to get better and that he was going to die, it was ‘eye opening.’

“She made it clear, ‘Grandpa is not gonna live. He is not going to survive this. This is not a disease that you come out the other side of. He will die.’ It was baffling to me,” Laboissonniere said. “At the time he was diagnosed he might’ve had tingling in his arms, but to me he seemed fine. But I didn’t realize that not everything has a drug. As a 13-year-old that’s hard to grapple with. He passed away less than a year later, in April, just after my birthday.”

Laboissonniere referred to a quote from the book “Tuesdays with Morrie” by Mitch Albom: “ALS is like a lit candle: it melts your nerves and leaves your body a pile of wax.”

“It’s a really sad disease. You’re being tube fed, you’re being washed by someone else, you can’t move, and we don’t know their mental health so we don’t know if they are aware of what’s going on, or if they have dementia or maybe they’re fully capable and completely reactive,” Laboissonniere said. “What a worse way to go, trapped inside your own body.”

She said she knew right away then that she wanted to study the disease.

“Lauren [Laboissonniere] performs some state-of-the-art molecular biology techniques to sample what genes are expressed in different populations,” said assistant professor Jeff Trimarchi. “This is much more difficult than it might sound and requires both wet lab molecular biology skill and skill in computational analysis of the large data sets.”

Laboissonniere studied these techniques at the University of Massachusetts when she was an undergrad in biomedical engineering.

When she came to Iowa State, she began to study the retina under Trimarchi. Trimarchi had a connection at Northwestern University, Dr. Hande Ozdinler, who works at the Northwestern School of Medicine and has a number of mouse models of ALS that Laboissonniere and Trimarchi have been able to use for their research.

“We look at the different genes that [the mice models] are expressing and we compare them to healthy mice at the same time points to see if there are genes that are being over-expressed or under-expressed that may be causing those cells to die,” Laboissonniere said.

Laboissonniere said the goal of this research is to isolate markers of the disease in cell populations, target them and test drugs that will attack the markers of the disease.

“We are really hoping to identify some sort of biomarker or something that we can target with a drug that can stop or slow down the disease progression, in hopes that it will translate back to humans,” Laboissonniere said.

Laboissonniere has examined multiple ALS mouse models and currently is in the process of publishing the results of this research.

Along with her research and the retina research with Trimarchi, she is in charge of a team of undergrad students working on a project studying zebrafish models of ALS.

“In all of these projects, Lauren [Laboissonniere] has done a wonderful job. She functions as a very independent researcher,” Trimarchi said. “Teaching herself the computational skills needed to analyze all of the data she has generated is particularly impressive.”

Laboissonniere is currently interviewing in labs for her postdoctoral research as she completes her doctorate this spring. She hopes to run an ALS lab of her own one day.