Panel discusses Columbus and the erasure of indigenous people groups

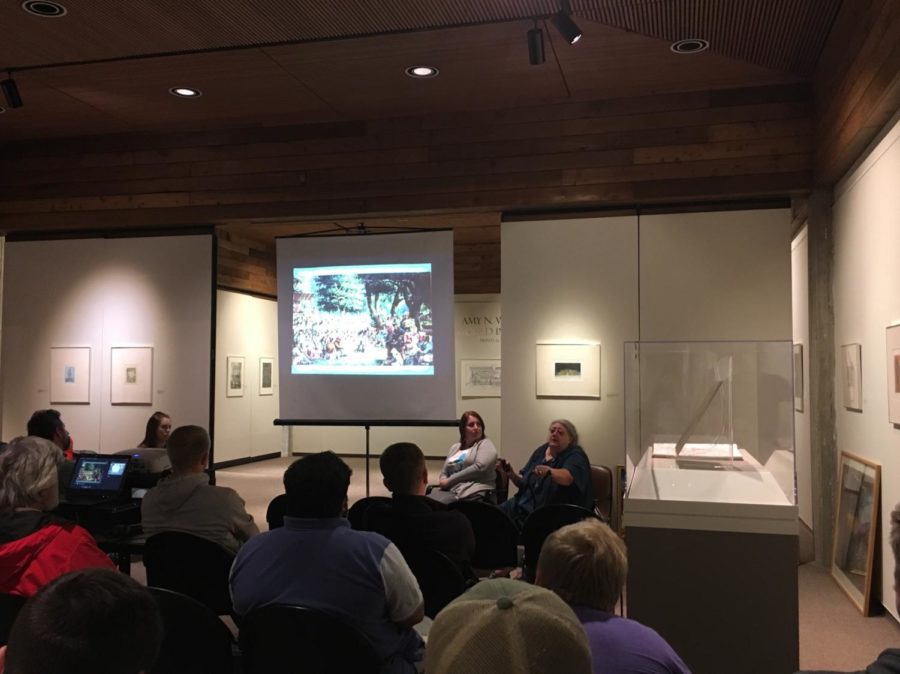

Melanie Van Horn/ Iowa State Daily

Lynn Paxson spoke to the crowd during Monday’s panel lecture about American Indians and their erasure due to Columbus and his colonization efforts.

October 9, 2017

In 1937, the United States declared Columbus Day to be a federal holiday recognizing the landing of Christopher Columbus, and the subsequent colonization of the “new world” by Europe. But while Europeans sought to advance their society, indigenous peoples faced the erasure and destruction of their culture and civilization.

On Monday, ISU students, faculty and Ames community members gathered for a panel discussion titled “Erasure and Invisibility: Columbus Day and the Representations of American Indians in Art.” Located at the Brunnier Art Museum, the lecture served as a discussion for the varying narratives surrounding Columbus and his impact on American Indians.

The panel included university faculty such as Christina Gish Hill, assistant professor in world languages and cultures, Lynn Paxson, professor in architecture, and Brian Behnken, associate professor in history. After an introduction by David Faux, interpretation specialist with University Museums, Hill spoke about the World’s Columbian Exposition.

As part of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, the city had a “columbian exposition,” a year-late celebration of Columbus discovering the “new world.”

“It really shows you how much anxiety there was around American Indians,” Hill said. “The exhibition was supposed to represent the pinnacle, the height of humanity.”

The World’s Columbian Exposition wanted to showcase Columbus as the beginning of civilization, and did so in an area of Chicago called the White City. In one Smithsonian ethnographic exhibit, mannequins depicted an “Indian Chief and Squaw.” The mannequin relied on stereotypes of American Indians, and contained no specificity as to what tribe the man belonged.

“The majority of the White City was about putting Euro-Americans on top, and native peoples on the bottom,” Hill said.

Another exhibit contained a federal Indian school that children actually attended for the duration of the World’s Fair.

“The whole point of the exhibit was about seeing them ‘climbing the ladder’ not as they are, or in terms of maintaining their own tradition, but adopting the Euro-American lifeway,” Hill said.

Behnken, who teaches Latin American and African-American Studies classes, spoke on racism in American popular culture, a topic on which he and Gregory D. Smithers, professor of history at Virginia Commonwealth University, recently wrote a book.

Racism in popular culture relates to archetypes and stereotypes that are created primarily for consumption by white Americans.

“It’s not always exclusive to North American people, but to indigenous people around the world,” Behnken said.

American Indian men can be characterized in two stereotypes, either the “noble savage,” or the “drunken warrior Indian,” Behnken said. Women are depicted as a “squaw,” which is tied to their sexuality, or the “Indian princess.” Paxson later noted that the term “squaw” is very offensive and should never be used.

Behnken pointed out numerous examples of these stereotypes in the media, in books, advertising, cartoons and film. In the children’s book “Little House on the Prairie,” a character says the line, “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

In older movies, white actors participated in “redface,” where a white actor would be cast to play a Native American part.

“The idea people had is that white people are so skilled that they can portray anyone, and they’re more authentic than the actual person,” Behnken said.

Paxson showed numerous cartoons and images about Columbus, the pilgrims, Thanksgiving, and indigenous people. One cartoon satirized the development of indigenous lands without regard for the impact on the environment.

“Then they’ll say, ‘Here, we’ve totally trashed this – you can have it back,’” Paxson said.

While many people think the lands that Europeans colonized were uninhabited, that isn’t the case. Many indigenous people had advanced civilizations with complex architecture, education and languages. According to Paxson, the Cherokee people had their own language, which was created by Sequoia. 90 percent of the Cherokee were literate, compared with only 20 percent of Europeans.

“We tell stories like it was him coming to an empty place,” Paxson said.