Harriet A. Washington speaks on dark history of medical ethics

Ian Steenhoek/Iowa State Daily

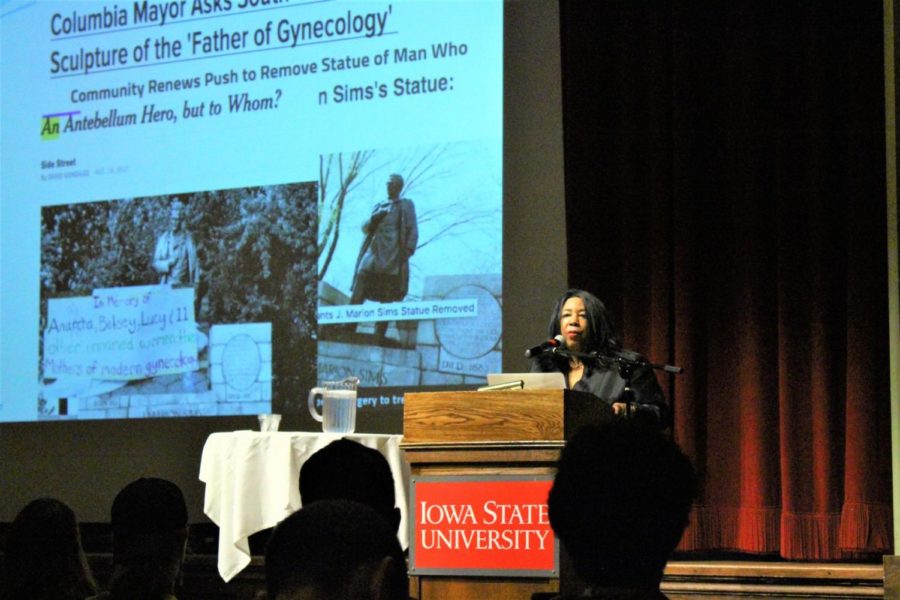

Harriet A. Washinton spoke in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union September 18, 2017.

September 19, 2017

Addressing a crowd of around three hundred in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union, medical ethicist and journalist, Harriet A. Washington disagrees with the fact that the birth of bioethics was in the 1960s.

For her, the field began at the end of the second World War, when American doctors and prosecutors confronted the Nazi architects of the Holocaust.

These were doctors who hid behind the guise of medical research to savage the abused and practice genocide principally against Jews. Washington mentioned the instance of widespread genocide in these people because of their ethnicity, hiding behind research.

“I can’t imagine a worse portrayal of medicine,” Washington said.

She went on to explain that although these prosecutors were accusing the Nazi doctors, at the same time, they were guilty of the exact same offenses right here in the States.

“Our hands are not clean, our hands are still not clean,” Washington said.

She stressed the importance of understanding what really happened during these hundreds of years of history because of the fact that it has been excluded from medical cannon.

Washington expressed her sadness on the offense some people have taken to her mission to finally include this history, because of her studies on the faults of people. This however, is not the case, according to Washington. She says that this is not about the faults of people, but about people whose abuse has been overlooked.

“It tells us something very important that we’d rather not know about our history, but we have to know and confront it if we’re going to do better in the future.” Washington said.

Washington continued with her lecture by speaking on how some people challenge her work by questioning how her writings can be about secret medical research when she found them in medical journals. She said, however, that one does not know the meaning of secrecy if they say that.

She pointed out the fact that it is not that doctors don’t talk about this type of research, it’s that they talk about it in places that, at the time, African Americans had no access to.

Another thing that contributes to secrecy, according to Washington, is literacy. Not literacy as in reading, literacy as in being able to understand medical jargon. Something she herself describes as “impenetrable.”

She also mentioned that in these medical journals, they tend to focus more on the technical aspects of the surgery and not on the abuse of the subjects.

Washington moved on by discussing the importance of knowing and understanding this history in order to understand where mid-American medicine is today. Trying to understand the divide between blacks and whites and the divide between subjects and researchers, doing this would be pointless and impossible to grasp without knowing the full story behind it.

“We have to know what happened in the past if we’re going to eradicate the negative behavior.” Washington said.

Washington then used an experience of her own as an example of how we have not yet said goodbye to an ugly history. This example was her involvement in a debate over the tearing down of a James Marion Sims statue located across from the Academy of Medicine in New York. She believed that the statue should be torn down.

What she found interesting were the arguments by people she considers moral and intelligent that are for keeping the statue. She believed that the fact that people defend Sims is based on the fact that they do not know the entire history, they don’t know what he did.

She went on to explain the work of James Marion Sims.

“James Marion Sims could be considered hero only if you ignore how he made his achievements,” Washington said.

He was an American physician whose most significant work was to develop a surgical technique for the repair of vesicovaginal fistula.

However, Washington clarified how he did so. His research used enslaved African-American women suffering from this complication from child birth and subjected them to surgery without anesthesia. After finding the cure, instead of treating these women, he decamped to other parts of the world where he became famous.

Washington went into many different ways racism was apparent back then and explained how these views are affecting people in this day and age, an effect she aptly refers to as a “hangover.”

One issue tackled in the lecture, was that of racial dimorphism. The belief that the bodies of African-Americans were so different from those of whites that they were considered and entirely different species.

“So the black body was basically alien. However, it wasn’t so alien that you couldn’t use it for medical research then practice the results on whites. Completely illogical, but very convenient,” Washington said.

Another issue that closely relates to the one above is that of the mythology of pain. Back then, there was a strong belief that black people did not feel pain. Sims defended his failure of not using anesthesia on black women by saying that it wasn’t worth the rick, that they did not need it.

Washington also mentioned that when clinics started up, black people were kept for longer periods of time in order to be observed. Mostly black cadavers were used for study in medical institutions without consent of family. She said that bodies and bones were being taken out of their graves in order to supply these institutions.

Washington argued that this lack of understanding black anatomy still happens in today’s society, and contributes to her “hangover” theory.

Examples of such are some people’s beliefs about the sickle cell disease, renal disease, malarial immunity, even “crack babies.” Washington said there are other causes as to why the number of people affected with certain diseases are predominantly black. These causes, however, are not entertained.

Another myth Washington talked about is the racial IQ gap, the belief that intelligence was hereditary and “color-coded.”

This difference in relationship between a black person and a doctor during the legalization of slavery, where though they were sick, they were not a patient due to the fact that their owner made all decisions regarding their health. This relates to the difference in relationship we have with our doctors regarding trust and treatment now.

The last big issue discussed in the lecture was that of tissue appropriation and consent. Washington talked about Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were taken and studied without her husband’s consent after her death to be studied because of their rarity. She also talked about John Moore, a white man, whose spleen was taken out without his consent and studied.

Consent forms of the past usually had wording like, “We’re going take your unnecessary, discarded tissues.”

“When you discard something, it doesn’t mean you lose interest in it. You can discard something and still have a concern over what happens to it,” Washington said.

Washington encouraged people to take a stand and do something to alert people to any ethical wrongdoings, no matter what their position. She said it is possible for one person who sees something wrong to stop it by refusing to be quiet.

“You can speak up and make a difference. [You can] stop something evil from happening if you have the bravery to speak up,” Washington said.