Exhibit shows ISU a leader in State Park creation, preservation

June 6, 2017

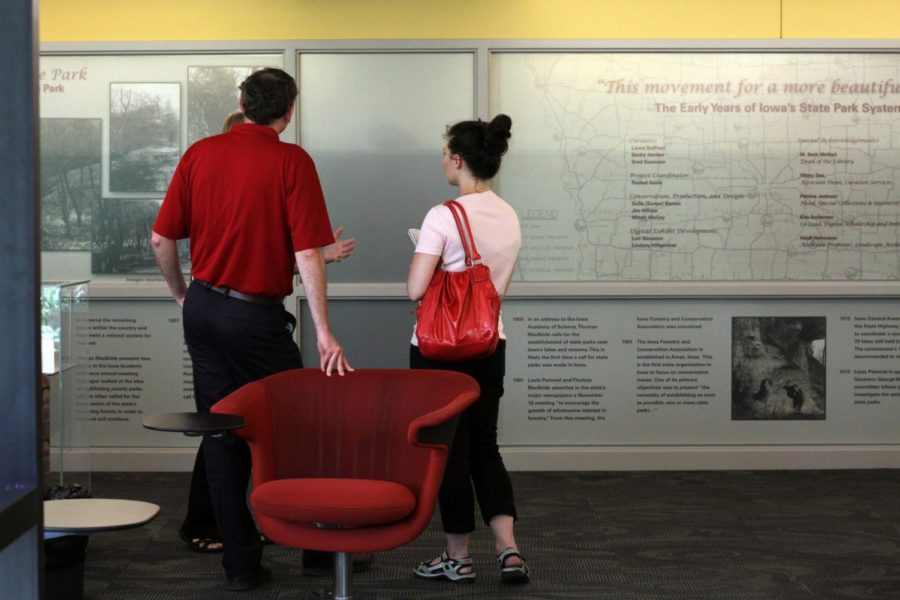

Special Collection’s Laura Sullivan, an outdoor enthusiast, knew that Iowa State botanist Louis Pammel was heavily involved in the creation of state parks and was looking for the opportunity to display some of the collection’s material on his work. That time came with the 100th anniversary of the state park system.

The exhibit highlights Iowa State’s role in the state park movement, and includes individuals from Iowa State such as botanists Pammel and Ada Hayden, forester G. B. MacDonald and landscape architect John Fitzsimmons.

Originally there was a proposed national park that would stretch from the Twin Cities down into Iowa, Sullivan said. Although that park fell through, state parks flourished. Iowa passed state park legislation within a few years of the federal government, and has been a leader in state park preservation, which turned the land that was being developed for agriculture back into natural habitats.

A brief history of the work to establish state parks in Iowa opens the exhibit, followed by background on Iowa’s first state parks.

Pammel played a key role, but so did the landscape architecture program. The program was in charge of topographic research and park design suggestions, which Fitzsimmons was specifically hired for. He oversaw students on the project until he became head of the department, special collections curator Brad Kuennen said.

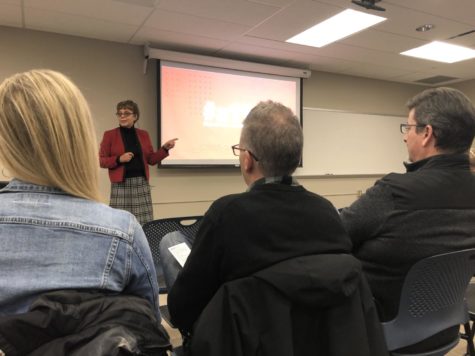

In conjunction with the exhibit Heidi H. Hohmann, associate professor of landscape architecture, gave a lecture Tuesday at the Ames Public Library. Hohmann’s lecture, “Designing State and National Parks,” focused on Iowa State and the Department of Landscape Architecture’s influence and role in the development of national parks and Iowa’s state parks.

The Landscape Architecture program was one in a small pool, and many of the staff came and went between such universities as Harvard and Cornell. In Iowa, the program focused on changing the rural landscape to improve lives, such as better roads to rural schools and better farmstead layouts for tree lines, building placement and soil use.

The National Park system was beginning, and public municipal parks were well received nationwide. Iowans had been lobbying for preservation land, and the park system worked with that.

“They wanted them to be parks, and they wanted them to be for the people,” Hohmann said.

The program was then asked, through its extension purposes, to work on the state parks. Roads within the parks, along with preservation and public enjoyment, were all parts of the puzzle.

“As overrun as we are today by imagery … I think we underestimate the significance in the view in the founding of the conservation management,” Hohmann said. “It wasn’t just about conserving natural habitat … it was about conserving scenery.”

Paintings of landscapes actually helped change public opinion to see the benefit of preserving scenery. That’s why the exhibit is called the Movement Toward a More Beautiful Iowa.

Landscape architects design roads to go with the natural topography – engineers prefer economy and the most cost-effective way, Hohmann said.

John Fitzsimmons and Philip Elwood, Jr. brought their expertise to the project and brought 1930s New Deal money to the state park project through work by the Civilian Conservation Corps, Hohmann said. Hohmann said because of that the people who worked on the planning of the parks get forgotten.

Fitzsimmons was able to hire other professors and students on CCC funding, which wouldn’t have been possible on the nine-month salaries the university went to during the Depression. Those staff planned the park system, studying typography and designing bridges, roads, amphitheaters, benches, shelters and even incinerators.

“How many different ways can you make a log bench? Betcha didn’t know,” Hohmann said.

A lot of the foreman where also landscape architects and engineer graduates, Hohmann said, which is why those untrained crews could complete those tougher projects.

A pattern book was developed of the designs for other states to use in designing their own parks.

“Iowa really became a leader in the design process,” Hohmann said. “That’s because they’d been working on it since the 1920s, they’d had ten years.”

It was rustic or naturalistic design, which worked to a master plan (no small “oops” decisions) and fit the typography, using native and local materials, such as the pavilions in Ledges State Park.

Ledges was the second state park in Iowa, and is still used by Iowa State researchers and classes. Pammel often took his classes there, and now Tim Stewart, associate professor in natural resource ecology and management, does. The exhibit concludes with examples on how Iowa State has used state parks since their creation and even includes a current student’s field notebook.

Some of the exhibit was provided by a current student employee, who was on a Department of Natural Resources trail crew last summer.

Visitors can view the exhibit on the fourth floor of Parks Library, and an online portion is expected through the library website.