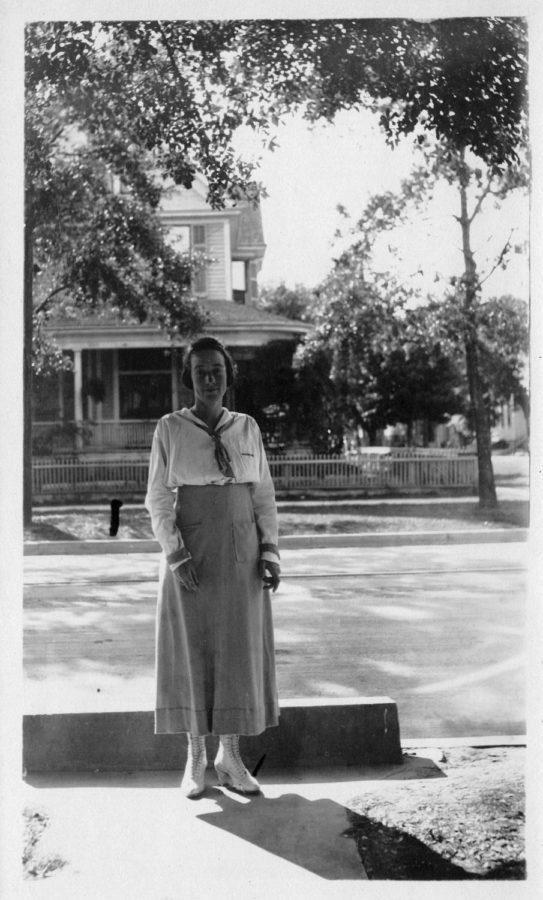

Ada Hayden: The First Woman at Iowa State to receive a Ph.D.

March 7, 2017

Born and raised in Ames, Iowa, Ada Hayden lived an inspirational life. From her fight to preserve the prairies to becoming the fourth person, and the first woman, at Iowa State to receive a Ph.D., she will always be remembered for her remarkable success.

It all started on Aug. 14, 1884, on a farm just north of Ames. During her childhood, Hayden developed a love for prairies that later showed in her work and her research. She enjoyed photography and writing, as well as her work in conservation, much of which included taking care of the land.

“She started out promoting conservation very early on and was really the first to try and push for setting prairies aside,” Deb Lewis, curator in ecology, evolution and organismal biology, said.

Hayden graduated from Ames High School in 1904.

Hayden was also well known for her connection to Iowa State. Around the time she was entering college, she was pushing for prairie areas to be preserved. At the time, the state did not protect prairies. Iowa had the state parks system, but it didn’t have the state preserves system.

She earned a bachelor of science degree in 1908. She then received a master of science degree from Washington University in St. Louis in 1910.

Soon after, she went back to Iowa State University after receiving her second master’s degree. This was around the time that Iowa State began the Ph.D program.

Despite the barriers of the time, she was able to get into the program and received her doctorate in philosophy in 1918, according to statistics in Special Collections and University Archives in Parks Library.

“The coolest elements of the story are first of all her history as a woman in science and then second, even more specifically, her history as a woman in science here at Iowa State,” Amy Bix, professor of history at Iowa State, said.

In the 1940s, Hayden received $100 from the Iowa Academy of Science to survey the state’s remaining prairies. By this time, a lot of Iowa had already been plowed up for growing crops because prairie soil is so rich.

She traveled around the state, visiting all of the different prairies that remained. This included wet prairies, dry prairies, sand prairies and more. During her research, Hayden proposed that the state consider 22 sites she believed represented the diversity of prairie in Iowa.

Hayden was an assistant professor of botany from 1919 to 1950 and was named curator of the herbarium from 1947 to 1950. During her career, she added more than 40,000 specimens to the herbarium. Today, it contains over 650,000 specimens in total.

“The thing about Ada Hayden of course is that she went so much deeper than a number of other women and then deeper than a number of men [by] going not only for a master’s degree, but a doctorate and then becoming an assistant professor,” Bix said. “She was pursuing at a very high level.”

Her work in conservation and with the herbarium was linked in the sense that she was out doing various kinds of studies even before she started her prairie project.

She did a survey of all the plants that grew in the southern part of Iowa’s lakes regions. While she was working on that, she was collecting samples of plants to document her work.

In late 1949, Hayden was diagnosed with cancer. She died soon after in August 1950.

Shortly after her death, the state bought three of the 22 prairies, one of which they named after her.

The Ada Hayden State Preserve in Howard County, Iowa, was named after Hayden by the Iowa Conservation Commission. In 1988, the herbarium was named Ada Hayden Herbarium, which can be found on Iowa State’s campus on the third floor of Bessey Hall.

In 2002, it was proposed that the land just southwest of the farm she had growing up in north Ames be named after Ada Hayden. After a lot of discussion and compromise, the park became Ada Hayden Heritage Park.

“She never married. She devoted her life to her work here,” Lewis said. “I wish I’d had a chance to meet her and talk to her.”