ISU Police addresses dangers through early intervention, training

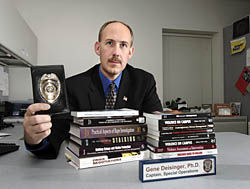

ISU Police officer Gene Deisinger specializes in threat management and crisis intervention.

March 24, 2016

It is no longer a matter of if, but a matter of when.

In the early 1990s, Gene Deisinger, retired threat management director at Virginia Tech, former associate director of public safety and former deputy chief of police at Iowa State, began working with a team to develop an approach to safety that would evolve into what is now — threat assessment and management.

Threat assessment, a process designed to identify, investigate, assess and manage instances of concern before they happen, is widely used across the nation and has been in action at Iowa State since about 1994.

The process can be used to identify any sort of threat to campus or workplace security, as no situation is the same. By intervening early, any potential danger is minimized.

When Deisinger and the team, which included current Ames Police Chief Chuck Cychosz, set out to develop a model of threat assessment, it was a relatively new approach that Deisinger had never heard of before.

Joking that the time period was pre-Google, Deisinger said in order to learn about threat assessment, the team had to find training sessions across the country where it would go to try and understand violence in the workplace and on campus.

An article published by the Daily in 1996 discusses this early program and what it meant for Iowa State.

Loras Jaeger, director of the ISU Department of Public Safety at the time, discussed the critical response team that Deisigner was a part of.

“It came from a desire to make campus as safe as possible,” Jaeger said in the article.

Being one of the first campuses to implement threat management, Iowa State looked at models similar to what they were trying to accomplish, such as other general violent models, and then adapted that for higher education work.

Part of the reason Iowa State began developing this model and looking for ways to improve the current system was because the fear hit too close to home after a shooting on the University of Iowa campus.

In November of 1991, Gang Lu, doctoral student in physics, shot six people, leaving four dead and two injured, before fatally shooting himself.

Deisinger, who had gone on to be the threat assessment director at Virginia Tech after the 2007 mass shooting, said they learned from and implemented some of their methods from this incident.

Questions were raised after the shooting as to whether any concerns could have been noticed beforehand and if the shooting could have been prevented. Deisinger said these same questions came up after Columbine, the Virginia Tech shooting and Sandy Hook.

“The earlier we can identify developing concerns, the earlier the concern can be manage and de-escalated,” Deisinger said.

The ISU Threat Assessment process is currently “designed to identify individuals of concern, investigate individuals and situations that have come to attention of others, and assess the information gathered.”

The last step, if necessary, is to manage the individuals and/or situations to reduce any potential threat.

Deisinger said by doing this, not only can the individual be assisted but they can also work to fix the systemic issue. He added that it helps build engagement across the community, and that it’s not just a police issue or a counseling issue, but a community issue.

The example he provided is when someone has the flu. If an individual noticed his or her friend was coughing or had congestion, he or she would most likely step in and tell the friend to stay home and rest. As a result, that person prevented the friend from potentially spreading the flu.

When it comes to threat assessment, early identification and the intervention process are most important.

However, Iowa State is still prepared for instances that require extreme measures.

While it is a scary thought not many care to entertain, the reality of a shooter or any other threat to campus must not to be taken lightly, and is a concept that ISU Police has not only recognized but is highly prepared for.

Last year alone, there were 23 shootings across university campuses nationwide, and 52 school shootings overall.

Prepared for any outcome, ISU Police has implemented a Violent Incident Response Training known as VIRT.

“Preparation is key for any situation we face in life; the more prepared we are, the better we perform,” ISU Police’s website reads.

About six VIRT instructors, including patrol officers such as Ryan Meenagh, go out into the ISU community and give presentations to groups on how to be better prepared in the case of a violent situation.

Part of the training involves informing the public on A.L.I.C.E., which stands for alert, lockdown, inform, counter and evacuate. A.L.I.C.E is a set of principles that are taught across the country to law enforcement, universities, schools, businesses and other organizations.

“The presentation generally starts off with a little bit of history and a little bit of a general warning over the topic that we’re going to be talking about,” Meenagh said. “It’s not really an easy topic to discuss from a standpoint of, ‘You’re supposed to be safe at school but the possibility of being attacked is ever present in today’s society.’”

When administering the VIRT training, ISU Police touches on what has happened in the past, common trends of an active killer and what they see intent being along the general behavior of a person who might be a potential danger.

In the second half of the training, they break down the A.L.I.C.E principles so participants know how to react in case they are in danger.

Meenagh said the training offers a chance to have an honest discussion about a very uncomfortable topic.