Unsolved Ames bombing remembered by its citizens

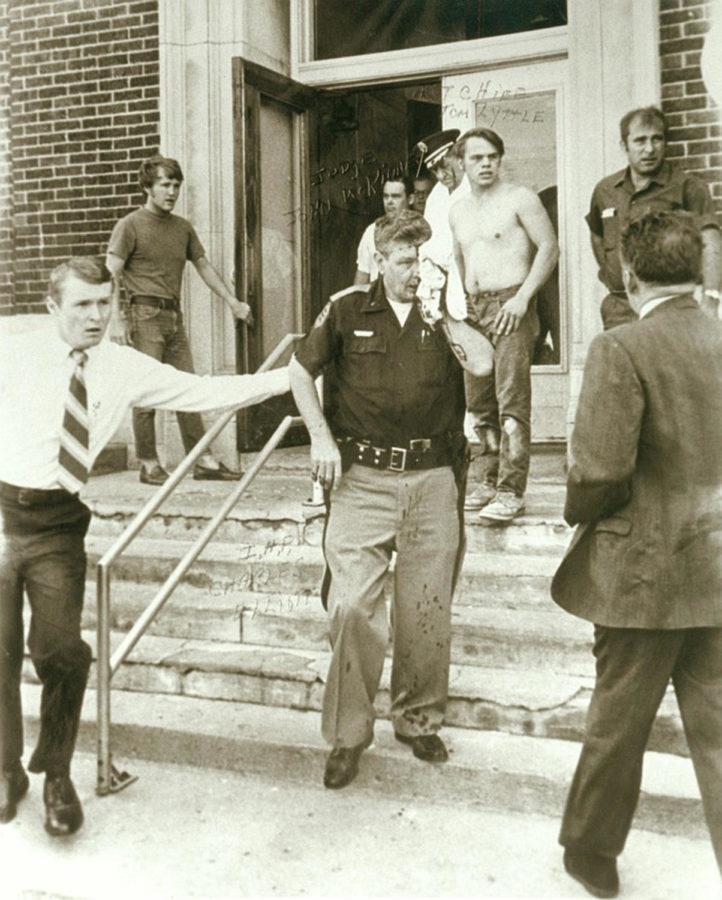

Charles Elliott, a Highway patrolman at the time of the bombing, lost an eye during the City Hall Bombing May, 22 1970.

November 12, 2015

A blast felt blocks away rocked the city of Ames in 1970, wounding nine police and city officials and causing many of them lifelong physical and emotional scars.

There are very few unsolved cases in the city of Ames and even fewer that involve nine wounded. But, in 1970, a bomb went off, and no one has been charged with the crime.

An unknown individual threw a bomb at the old Ames City Hall at the corner of what is now Kellogg Street and 5th Street on May 22, 1970.

“It was a peaceful place, and a lot of people didn’t even lock their doors,” said Myrna Wilhelm Elliott, resident of Ames and widow of highway patrolman Charles Elliott, who was wounded in the attack. “This racial thing in Des Moines was going on, but nobody even thought it was going to happen here.”

Mryna was in Minnesota when a neighbor told her that her husband was involved in a bad accident. She said she initially thought her sons were involved in a car accident. Law enforcement officials sent a patrol plane to pick her up and take her to Ames.

“At that point, I didn’t know if he was alive or what,” she said. “They wouldn’t tell me, and, being a nurse, I knew nobody ever told if they died.”

Charles had a head injury, a broken jaw and he lost an eye. Mryna said she spent 30 years picking glass out of his head that she would notice by the shine.

“The doctor told me that if that little shard of glass had gone less than an eighth of an inch [in another direction] it would’ve killed him,” she said. “Afterward, he was very suspicious of everybody and everything and [was] so different than what he was before.”

Charles retired three years after the bombing.

Bonnie Norman, an ISU alumna who graduated in 1975, lived near Ames City Hall at the time of the bombing.

“I was awake, and I felt the bomb,” she said. “I knew something big had just happened.”

Norman agreed that Ames was a quiet college town before the bombing. Her boyfriend was in Vietnam at the time, and she had participated in a protest march against the war.

The United States was in a time of turmoil and change that seemed to affect every part of the country during the 1970s.

The bombing was a jolt to the citizens of Ames, Norman said.

“We all felt a little more worried like that something like that could happen again,” she said.

Doug and Wendy Livy were living in Ames at the time as well, and they owned a bar called the Red Ram near a railroad on what is now a vacant lot now on South Kellogg Street.

Wendy was student teaching out of town at the time and noted that the air was somewhat thick around Ames.

“Quite a bit of tension actually,” Wendy said. “There was some racial tension.”

Doug said black students had been protesting at the Memorial Union.

There was a lot of racial unrest around the country at the time, Wendy said.

“We didn’t have many students of any color besides white in our classes at that time,” she said.

Before the bombing, the Livys had an altercation at their bar. While Doug was in Iowa City, a patron of the bar named Chuck Jean was hit with a beer stein.

“This happened at the bar, and the guy that hit him was black,” Doug said. “Chuck was white. The guy left the bar, and a half an hour later he was back at the bar with, I don’t know, about 20 black students. People that didn’t think that the blacks were organized on campus, they had a second thought coming.”

Jean was arrested the next day, and Doug paid his fine for the offense.

“The police ended up closing the bar, which was the right thing to do, before things got out of hand,” Doug said.

There were three other bombings around that same time in central Iowa.

One bombing occurred at the Des Moines Police Station on May 13, 1970; a second bombing happened at the Des Moines Chamber of Commerce on June 13, 1970; and another went off at the Harvey Ingham Hall of Science on the Drake University campus on June 29, 1970.

The suspect, James W. Lawson Jr., was killed in a botched explosion in Minneapolis on Sept. 6, 1970. He had been living in the Black Panther Headquarters, according to an article from The Des Moines Register.

The police identified Lawson at the Minneapolis bombing posthumously by his dental records.

While the bombing remains unsolved, those who remember the incident said they will never forget.