More than a game: ‘Miracle on Ice’ continues to influence hockey in America after 35 years

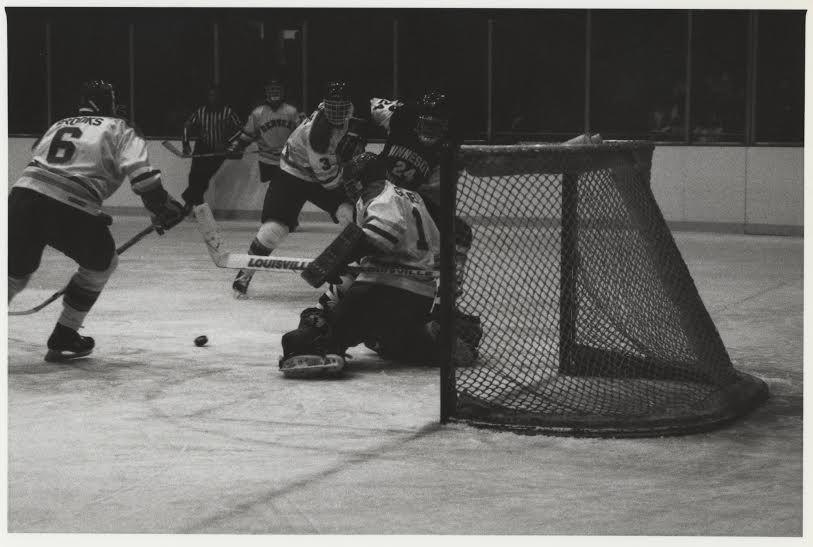

Courtesy of University of Denver

Cyclone Hockey coach Jason Fairman played with Dan Brooks, the son of U.S. hockey coach Herb Brooks. Herb led the U.S. hockey team during the famous Miracle on Ice game against the Soviet Union. Sunday marked the 35th anniversary of the win.

February 23, 2015

Stranded in a hotel in North Dakota, Jason Fairman and other players on the University of Denver men’s hockey team crowded into the hotel room. A typical North Dakota snowstorm blew through the town the night before and the team was informed it would not be leaving for two days.

Fairman and the other 10 men in the room huddled around the lone television. On came “Miracle on Ice,” the original 1981 film depicting the magical 1980 U.S.A. men’s hockey team’s win against the heavily-favored Soviet Union in the Winter Olympics on its way to an eventual gold medal.

Alongside Fairman was his roommate, Dan Brooks, and he wasn’t shy offering his input on the film. Of course, Brooks had heard second-hand of what happened from his father, Herb, who was the head coach of the infamous hockey team.

Fairman remembered the time when he learned about the game. It was on tape delay, so it was just his luck that someone ruined it by telling him the outcome. Nevertheless, he felt the national pride that most others in the country felt.

“I think a lot people need to realize what a big upset that was,” the now-Cyclone Hockey head coach Fairman said. “I was too young to have anything other than national pride.”

What the Miracle team did for Fairman, it did for Americans all across the nation. It engulfed their spirits in a time when international relations were characterized by high tensions during the Cold War. Considering the surrounding circumstances, the U.S.A.’s victory could be regarded as the single most important sports event of the 20th century.

The story seemed like one straight out of a book. The Soviet Union manhandled the U.S.A. team 10-3 just a few days before the Olympics were slated to begin in Lake Placid, N.Y. The Soviet Union at that time had won four gold medals in the four previous Winter Olympics.

But the amateur U.S.A. team composed of collegiate hockey players made it to the semifinal and earned another shot at the perennial champions.

U.S.A would fall behind 3-2 in the first two periods, but after a goal to tie the score, Mike Eruzione found the back of the net for the fourth and game-winning goal. With seconds left to go in the game, broadcaster Al Michaels delivered the famous line, which helped give the game the nickname — Miracle on Ice:

“Do you believe in miracles?! Yes!”

________________________________________

The Cold War on ice

The 1980 Winter Olympics was held in a time of political turmoil between the two superpowers, the U.S.A. and the Soviet Union. It was just following the beginning of what some people called “The Second Cold War.”

In the period leading up to 1979, the Cold War had quieted. Throughout the 1970s there had been few major crises between the two countries and there were actually the beginnings of friendship talks between the two sides.

That all changed in December of 1979 when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. The U.S. government had given support to Afghanistan before the invasion, aiding the anti-communist fighters. The invasion set off a large chain of events that would spin both countries into a tension-filled climate that extended through the 1980 Olympic Games.

Sports were no exemption from the Cold War, in fact, they were at the forefront for one of the sides — the Soviet Union. There were many instances during the Cold War when athletes from the Soviet Union were given various human growth hormones to improve performance, especially female athletes.

“The Soviet’s sports system was established throughout the summer and winter games with explicit aim of winning for reason of prestige to prove that the Socialist regime were superior to the Capitalists,” said ISU political science professor Richard Mansbach.

The prestige was certainly highlighted by one sport specifically — hockey.

The Soviet Union had dominated the international hockey scene in the years prior to 1980, winning five gold medals in the previous six Olympic Games. Heading into the 1980 Olympics, the team had to have one thing on its mind — winning another gold medal.

As the showdown loomed on the horizon, the news buzzed about how important this game was to not only the hockey world, but the international political scene.

“The Olympics are hardly apolitical. Nothing is apolitical in this world. The Olympics are the last thing,” Mansbach said. “So in a sense, the hockey match was a Cold War, literally and figuratively.”

Draped in the irony of the Cold War playing out on actual ice, the U.S. pulled off the improbable upset and continued on to beat Finland in the gold medal game.

What it did for the people of America and the American Administration was much more profound.

“It enhances the reputation of the administration, even though it had nothing to do with it. Simply, citizens bathed in the glow [of the win] that somehow capitalism, Americans [and] the free world had won some type of significant, symbolic victory,” Mansbach said.

________________________________________

Influence of a nation

Ask any American hockey player about the story of the USA team, and they will tell you about a story in their childhood or a story from their father who watched the game. They will be the first ones to tell you how important that game was to the country and how important it was in their career.

The 1980 Olympics are seen to some in the industry as the “turning point” in the lifeblood of America’s hockey program. Rather than only the northern states — which had a culture built in around the sport— participating in hockey, the majority of other states joined the youth movement of hockey players.

The period in the 1990s, 10 years after the game, youth hockey had around 200,000 kids enrolled. 15 years later that number climbed to about a half million. That may be due in part to parents telling emotional stories to their kids about the 1980 Olympics, inspiring a wave of youth interest across the nation.

For Cyclone Hockey goaltender Matt Cooper, that’s exactly what happened.

“It’s one of the pinnacle moments growing up a hockey player that you think of,” he said after returning from playing for team U.S.A. at the World University Games. “I remember my dad telling me stories about watching the replay. It was a big memory and a big motivator for my career and any hockey player’s career.”

The game still influences hockey players today. Despite the ages of some of the current hockey players excluding them from experiencing the moment firsthand in 1980, it still serves as influence to American kids.

“It’s inspiring. It’s the best underdog story that ever was if you’re an American,” said Cyclone Hockey forward J.P. Kascsak. “It was a miracle, it gets anyone going, any hockey player really.”

In recent weeks, Cooper and Kascsak learned the feeling of putting on a red, white and blue jersey and representing their country first hand. Earlier in February, they were shipped to Spain with 20 other American Collegiate Hockey Association players to play for team U.S.A. in the Winter World University Games.

They finished sixth and also beat Kazakhstan, which was part of the Soviet Union during the 1980 Winter Olympics.

“Playing for U.S.A. and [to] contribute to the bank of American hockey was [an] extremely awesome experience,” Cooper said. “It’s awesome having that heritage to that back in the day. We beat Kazakhstan, so it is really cool to have those ties. I think [of] myself as a junior Jimmy Craig, [U.S.A. goaltender in 1980], to make the country as happy as he did.”

The game’s reach 25 years later displays how it was so much more to the nation than just another sporting event.

It encapsulated everything into one moment — one win.

“It was such an unbelievable moment in sport’s history,” Cooper said. “It’s the epitome of hockey.”