Some states turn to performance-based funding for college success

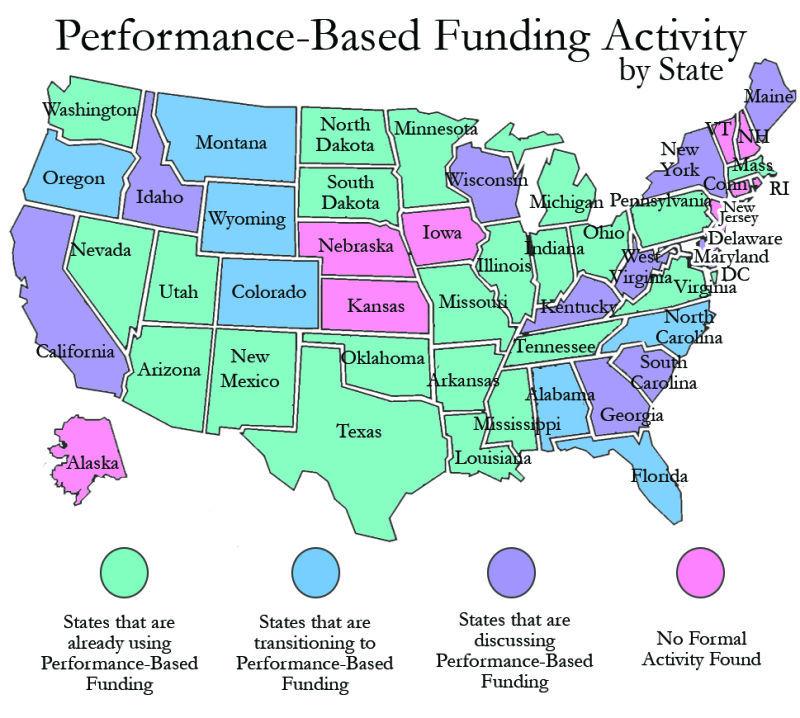

Infographic: Azwan Azhar/ Iowa State Daily

In the United States, there are states who already use Performance-Based Funding, transitioning, discussing and there are those who has no Formal Activity.

October 2, 2013

For over a decade, there has been an interest in kindergarten through 12th grade education using performance-based funding. Now the Obama administration has put an emphasis on using it at the post-secondary education level.

The performance-based funding method allows states to implement laws and mandates to tie higher education funding to classroom performance.

The method is used to develop measures for college success, and states give money to colleges and institutions that meet the state’s set indicators, which can then be spent to increase programs.

Janice Friedel, associate professor of education, and Zoe Thornton, an ISU graduate student, became interested in tracing the development of performance-based funding across states. They wanted to see if it makes a difference in a student’s success and if it really has an impact on more people completing college.

The study’s goal was to show that this type of method is being used and bring awareness to what and how it is happening.

In order to do this, Friedel and Thornton monitored state legislative committee websites, national council state legislator reports and talked to state directors of community colleges. The study was Thornton’s doctoral capstone project and resulted in the final report, “Performance-Based Funding: The National Landscape.”

The two stated what the benefits and pitfalls of tying funding to performance measures are. In their report, they gave recommendations to states on how to make performance-based funding work for them.

“Often states want to have an immediate fix, see immediate improvements and it doesn’t work that way,” said Friedel.

So far, there has been little evidence that performance-based funding has increased performance. Some of the recommendations made in the report were to give more time in order for the strategies to be fully implemented. These results may take years, and states should not expect to have changes in one year.

Both researchers agree that not all states are correct for using performance-based funding, and that Iowa may not be the best place for it either.

“Each state has different needs, goals, agendas and this is not necessarily right for all,” Thornton said.

The priorities and goals of the higher education institutions in Iowa are linked very closely with the state in regards to continuing education for a better workforce. This includes a strong relationship with community colleges and four-year institutions in terms of transfer plans for an easier transition.

“There is a definite connection and support of state goals for workforce and economic development in Iowa, and based on the strength of the partnerships in place I don’t know that there is a need for performance-based funding in Iowa at this time,” Thornton said.

Friedel and Thornton plan to keep researching on how this method impacts states.

Since this is the only report available as a review of performance-based funding, when new information is released Friedel and Thornton plan to continually add to their report to give policymakers a resource for understanding performance-based funding.