Deaf Awareness Week

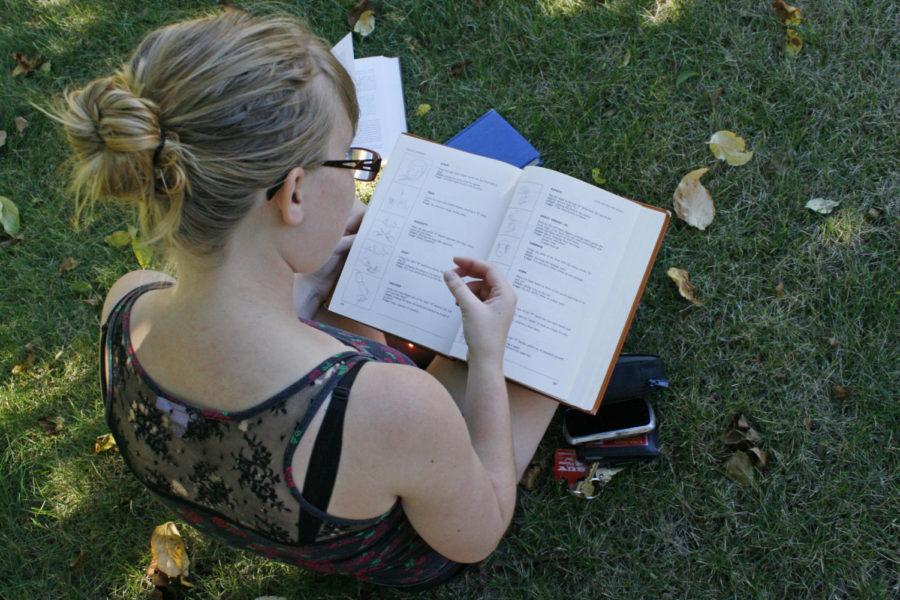

For the first time since 1972, the state of Iowa is celebrating Deaf Awareness Week. One thing students can do to raise their awareness is to learn some sign language. Many books are available on the subject at Parks Library.

September 23, 2013

Bob Vizzini is a lecturer at the University of Iowa. He has traveled to Korea, Japan, Hong Kong, Thailand, Canada, the Philippines and Hungary to meet with foreign leaders. While in Canada, he was an assistant pastor. He moved from Washington state to work in Iowa City. Vizzini is married with five children.

All of these accomplishments have been experienced with only four senses. Vizzini has been deaf since the age of five from spinal meningitis. His wife, Sharon, was born hard of hearing, but grew deaf gradually.

For the first time since 1972, Iowa will be celebrating Deaf Awareness Week.

Gov. Terry Branstad signed a proclamation request from the Iowa Department of Human Rights to declare the week of Sept. 22 to 28 as Deaf Awareness Week.

“[Gov. Branstad] did so because proclamations are a way to highlight particular issues and promote particular items,” said Tim Albrecht, communications director for Branstad. “The governor thought this was a really important issue to make sure we recognize the important contributions the deaf community makes on behalf of the people of Iowa.”

Iowa is home to 307,400 to 430,300 deaf or hard of hearing people. The large range of approximation is due to some deaf citizens’ hesitance to share they are deaf on the census, Vizzini said.

In alliance with National Association of the Deaf and the World Federation of the Deaf, the week is focused on raising awareness of the deaf community’s contributions to the state of Iowa, as well as informing the public of struggles they face.

Vizzini communicated with the Daily via video phone service with an interpreter.

“Some deaf people do feel intimidated … because [being deaf] seems to be a negative thing,” Vizzini said. “[They] feel inferior.”

Because of this, Vizzini said the estimate as to how many deaf students attend Iowa State might be more than recorded.

Steve Moats, director of Student Disability Resources, said Iowa State works with approximately six students who use sign language and use a live certified sign language interpreter in class.

Vizzini said he would estimate about 10 or 12 deaf or hard of hearing ISU students who have not identified themselves.

“They don’t want to tell the disability office that they’re deaf or hard of hearing …because they don’t want that identity … so they get left out of the count,” Vizzini said.

However, Student Disability Resources does offer resources to deaf and hard of hearing students, including providing certified interpreters and captionists as well as working with professors.

“Certainly they have a different learning experience than a hearing student does,” Moats said. “The accommodations that we provide help them participate and access the course materials.”

Iowa State works with agencies in the area to contract services from certified interpreters. Interpreters attend classes with the student and any meeting that would require assistance, such as a financial aid meeting.

“Our office exists to assist students and their professors,” Moats said. “We’re here as a resource to them.”

Student Disability Resources employs only one interpreter on staff, Jonathan Webb, but he is only an interpreter 40 percent of the time. He is also a lecturer teaching American Sign Language classes in the world languages and cultures department.

“American Sign Language is not used much in Iowa. It kind of feels like Iowa is a little behind the time,” Vizzini said. “We need more interpreters in Iowa.”

Vizzini said the Iowa School for the Deaf is dwindling in numbers because the public schools are starting to include interpreters, which encourages the deaf students to attend the public schools.

“They think throwing an interpreter in the classroom is enough, but really it is a weak system,” Vizzini said. “We need to bring up the quality of our interpreters for our children.”

Although students who are deaf may learn a bit differently than a hearing student might, Moats said they are equally as capable.

“Students who are deaf or hard of hearing can major in anything that any other student does,” Moats said.

Vizzini said some of the main concerns for the deaf community is equality in the work place and the need for quality interpreters in the legal and school systems.

Though both Vizzini and his wife are deaf, all of their children can hear. The oldest of their kids is a certified American Sign Language interpreter in North Carolina.

Vizzini said when he informs people his children can hear, the usual response is one of a shocked, “Oh, how wonderful.”

He said the public just does not understand deaf people can do just about everything people who are able to hear can.

“I’m proud to be deaf. And I encourage children to be proud of our deafness,” Vizzini said. “[I want] to tell them we can be very successful.”