Vaccinate chickens to get healthier humans

February 5, 2013

Gut-wrenching pain. Vomiting. An extended stay in the nearest restroom facility.

Those who have experienced or witnessed the mind-numbing, body crippling effects of gastroenteritis, which is more commonly known as the stomach flu, know there is no simple cure other than to endure and wait the bug out.

However, this disease may be about to meet its match.

Led by ISU College of Veterinary Medicines faculty, a team of researchers from the University of Ohio State and University of Tennessee work together on a project that will formulate preventative measures and strategies to combat one of the main instigators behind food-borne illnesses, a bacteria called Campylobacter.

“[Campylobacter] casues 800,000 food-borne [illnesses] in the United States alone,” said Qijing Zhang, associate dean in the ISU College of Veterinary Medicine and leading project director.

The team recently received a $2.5 million grant from U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Over the next five years, the project team will develop strategies and management measures to reduce campylobacter infection in chickens, Zhang said.

The end-all goal is to create a safer supply of chickens for human consumption and healthier animals.

Zhang said the project seeks to address problems at each step in the food processing chain to identify the stages where contamination occurs.

Orhan Sahin, ISU research assistant professor in the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Preventive Medicine, said ISU researchers are trying to identify the management factors on farms and meat processing plants to promote proper biosecurity safety measures.

“We are going to test each step in commercial environments to see which steps are increasing the chances of [chicken] carcasses being contaminated with this organism,” Sahin said.

The bacteria has a major animal reservoir, which are animal hosts, Zhang said. Campylobacter is so common that a lot of chicken farms have it.

“The bacteria is hard to control,” Zhang said. “It’s very hard to remove from the chickens because they don’t show symptoms of illness.”

Somewhere along the way, Sahin said the pathogen infects chicken carcasses in meat processing plants.

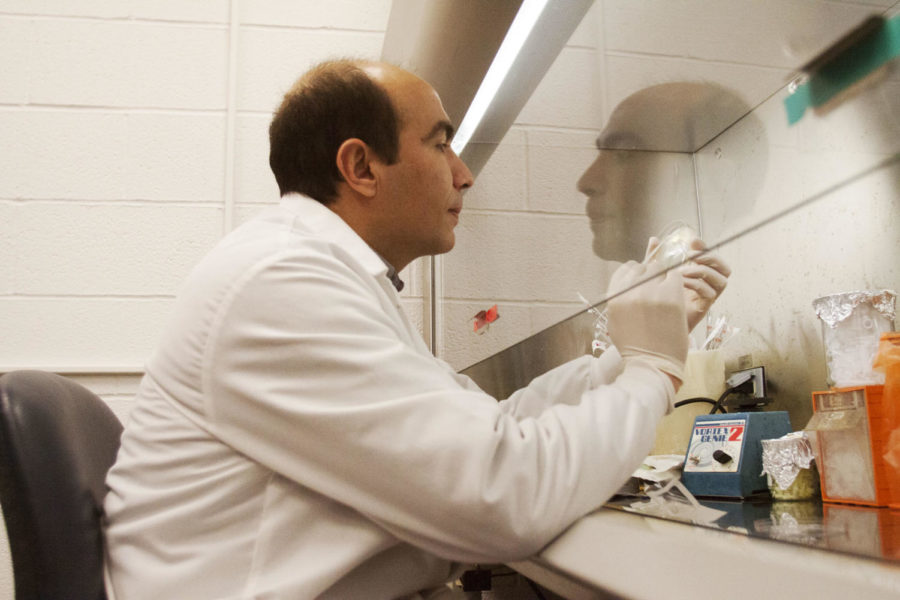

So the team researchers in Iowa State’s Vet Med labs conduct genetic, biological and immunological studies to better understand how the bacteria functions to create strategies that will effectively contain the pathogen.

Similar to vaccinations for humans to prevent influenza, Sahin said vaccinating chickens gives them more protection against campylobacter infection.

“We are trying to reduce the infection level on the chicken farm and processing plants,” Sahin said. “It’s really challenging because chickens never get sick or show symptoms of the bacteria infection.”

The vaccine must be formulated so that it stimulates protective immunity in chickens. Vaccinating chickens is important because of the disease campylobacter causes in humans, Sahin said.

While the researchers develop strategies and management plans, consumers can take some simple steps for food safety in the kitchen to prevent infection.

“It’s very common to find the bacteria in chicken bought from supermarkets and local grocery stores,” Zhang said.

A lot of contamination comes from cross contamination during food preparation. It’s important to properly cook raw chicken and wash off utensils used during the process before preparing something like a salad, Sahin said.

Eating not only the undercooked chicken but also the cross-contaminated food transmits food-borne illnesses.

Sahin and Zhang both agreed that this isn’t a reason to be paranoid, but campylobacter is one of the more significant problems concerning food safety today.