Apollo’s impact still felt today

July 23, 2019

When the Columbia — the command module carrying the Apollo 11 astronauts — splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969, the shockwave of its impact reverberated around the world and back and forth through decades of history.

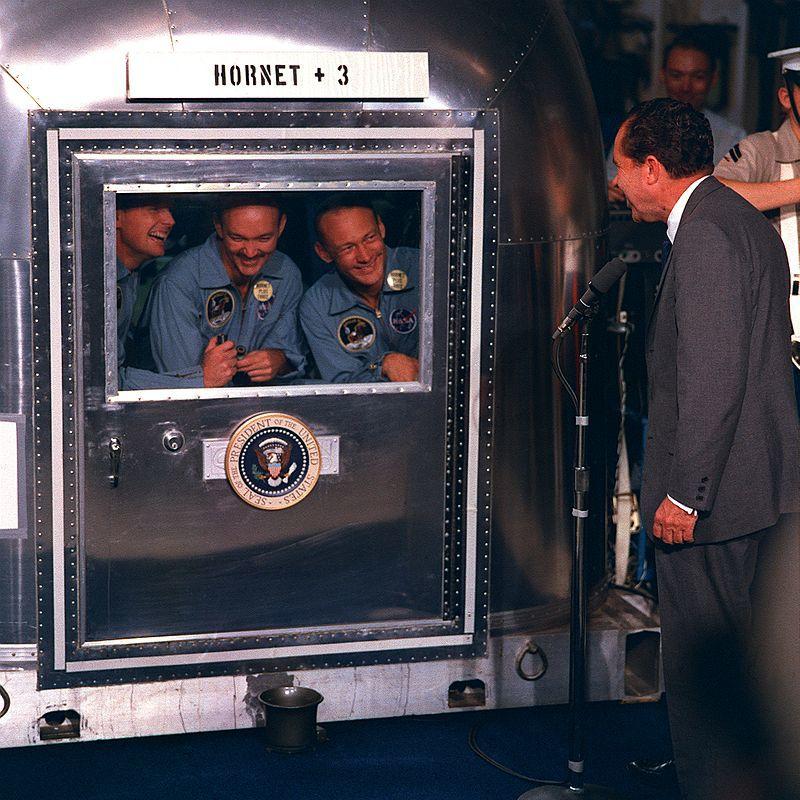

After bobbing around in the Pacific for several minutes, the astronauts —Michael Collins, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin — were fished out of the water and brought aboard the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, where they were held in quarantine for 21 days to prevent any possible lunar pathogens from spreading on Earth.

Their achievement, going to another world and returning to Earth in the case of Armstrong and Aldrin, came less than a decade after the first man orbited the Earth: the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin.

The astronauts were honored with ticker-tape parades in New York and Chicago before they embarked on a 22-nation world tour.

One small step for a man, one giant political impact for mankind

The United States built up “soft power” after the Apollo moon landing, said Richard Mansbach, a professor of political science.

“Soft power refers to getting others to follow your leadership, because they admire what you do and how you do it, and so they want to copy you,” Mansbach said.

An estimated 600 million people around the world watched Armstrong take his first steps on the moon out of an estimated global population of 3.7 billion.

“There’s no question that the space race was a very large part of the rhetoric of the Cold War,” said Tim Wolters, an associate professor of history.

Wolters added the collapse of the Soviet Union and its defeat in the Cold War had more to do with its “failure to keep up with IT.”

Domestically, President Richard Nixon saw his approval rating jump by 4.1%, while his disapproval fell by 1.4% from before and after the Apollo 11 landing took place.

President John F. Kennedy had called for Americans to put a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s in a May, 1961 speech. Kennedy did not live to see it happen, having been assassinated in 1963.

However, the beginning of the American initiatives that eventually culminated in the Apollo landing go back even further.

World War and Nazi Roots

The American space program has its roots in World War II, alongside the “birth of modern rocketry.”

Towards the end of the war, the United States and the Soviet Union raced to gather German research and development materials — and the scientists behind them — to bolster their own rocket programs.

Wolters said that effort — known in the United States as Operation Paperclip — aided American rocket development.

“I don’t think it’s incorrect to say that the infusion of German scientists — some of whom were Nazis — did give a boost to the U.S. rocket program,” Wolters said.

In his book “Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State,” Brian Crim, an associate professor of history at the University of Lynchburg, discusses the role of those scientists in the development of the American space program, and their background.

“German scientists prolonged the war through their efforts and prospered under the Nazi regime,” Crim wrote. “Some were uncritical supporters of National Socialism, others more passive, but none of the ‘Paperclippers’ achieved the impressive results so attractive to US authorities by opting out of the regime.”

One of the “leading” scientists was Wernher von Braun, who during the war worked on the V-2 rockets used by the Nazi regime to target London.

Following the launch of Sputnik 1, amid the technological rivalry between the United States and Soviet Union, there was a false belief among Americans the Soviet Union was “outstripping the United States technologically,” Mansbach said.

In 1960, not quite fully three years after Sputnik 1 launched, Von Braun was appointed director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center and “chief architect of the Saturn V launch vehicle, the superbooster that would propel Americans to the moon,” according to a NASA biography about him.

A moonshot for modern technologies

While the roots of the Apollo Program date back to World War II, the effects of it and the wider space program continue to be felt today.

“Miniaturization really begins with the Apollo Program,” Wolters said.

In order to fit all of the material needed to sustain life on-board the cramped spaceships the Apollo crews used, NASA and contractors had to miniaturize. Among the miniaturized components were the computers for command and control.

The miniaturization of technologies that allowed for the Apollo Program’s success continues today with cell phones, smart watches and similar technologies.

It is also possible that the development of the rockets for the space program spared the world from nuclear war.

During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union had thousands of nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles aimed at each other. However, there was a strategic balance known as mutually assured destruction (MAD).

The overlap between civilian and military rocket development was often blurred at this time, and the solid fuel rockets developed which put men in space could also be used to deliver submarine launched ballistic missiles, ensuring the strategic balance of MAD.

Future space travel

No humans have stepped foot on another world since the Apollo 17’s 1972 moon landing.

President Donald Trump and the surviving Apollo 11 astronauts called for a manned mission to Mars in an Oval Office meeting Friday.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine has pushed back on Trump’s insistence on bypassing the moon and traveling straight to Mars, saying NASA needs to return to the moon as a “proving ground” for a future Mars mission.

During the Apollo Program, there was never majority support among Americans for the spending required to finance the sending of astronauts to the moon.

Support for funding on a manned mission to Mars reached 53% support among Americans in a Gallup poll released July 11.

There are no current missions planned by NASA for a manned touchdown on the Martian surface.