Nobel Prize winner Shechtman encourages ISU community to stand up to criticism

February 20, 2012

The excitement was tangible in the noisy Great Hall of the Memorial Union. Hundreds of people came to hear about the Nobel Prize-winning discovery of quasicrystals and rose to their feet in appreciation and recognition when Dan Shechtman concluded his lecture.

“It was inspiring,” said Yvan Gugler, non-degree engineering specials student. “I’m very impressed by Dr. Shechtman’s courage, even when he had so many opponents.”

Shechtman, a professor at Iowa State and Technion-Israel Institute of Technology and scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for a discovery that was contrary to the rules of crystallography and every definition of a crystal that had previously existed.

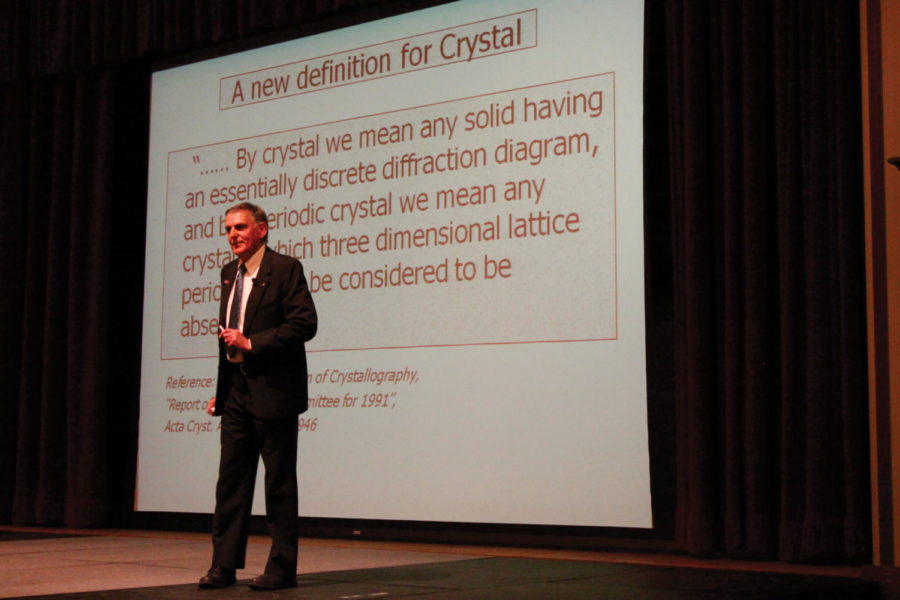

Hundreds of thousands of crystals had been studied and all were found to have a structure that was ordered and periodic, or in other words organized and at fixed intervals. The structure that Shechtman discovered did not fit into the accepted orders and was not periodic.

The man, whose success “created a phase change in his life,” laid out his lecture in a way that non-scientists and scientists alike could understand how his discovery worked and its importance. He strolled across the stage from right to left and back again, stopping to emphasize a point or to crack a joke.

“We all ought to think about rewriting textbooks as a goal,” said ISU President Steven Leath as he began to introduce the scientist who made Iowa State’s College of Engineering one of four in the world that has a Nobel laureate currently on faculty.

Shechtman made the discovery on April 8, 1982, and denoted it in his lab notebook with a simple “(10 fold??).” Between 1982 and 1984, no one believed Shechtman. Colleagues said he was wrong and that they were embarrassed by him. They would even put textbooks in front of him and tell him to read. After Shechtman was published in 1984, there were some crystallographers who became convinced, and after extensive work, the International Union of Crystallography accepted his findings in 1987.

“When the paper was published,” Shechtman said, “all hell broke loose.”

There was still significant resistance, however, between 1987 and 1994, which was led by two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling. Today, 100 years after the establishment of crystallography as a discipline, the definition of a crystal stands corrected and thousands of scientists stand humbled by Shechtman’s work.

Shechtman gave advice to ISU students and faculty by encouraging everyone to be professional, believe in themselves and have courage. These words of insight came from a man who answered a question on a test as a student in college about how the very structure he discovered many years later could not exist.

“Find something that you like and become an expert,” Shechtman said. “And I promise you, you will succeed in your career.”