Belding: Arts and humanities just as valuable as science

Graphic: Kelsey Kremer/Iowa State Daily

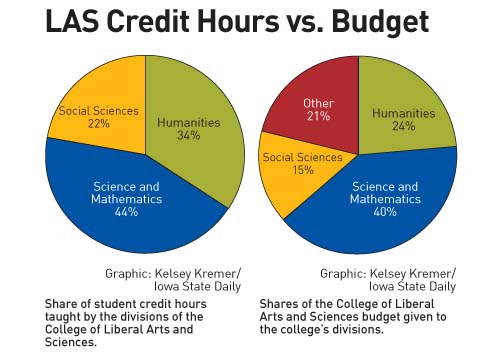

In 2006, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences sent 40 percent of its budget to departments grouped as science and mathematics, which teaches 43 percent of student credit hours. The humanities and social sciences, meanwhile, received 38.8 percent of the budget to teach 55.75 percent of student credit hours.

November 28, 2011

Vanity, arrogance, presumption and conceit are the marks of any scientist who assumes that his discipline provides more of the answers to human existence than the arts and humanities or social sciences. Disciplines that may not be of profitable use are the ones that validate our existence as humans.

Facts are very nice, and so is rational thinking. Science has undeniably given us important conveniences that free our time and improve our standard of living, but valuing science at art’s expense makes men into machines who are unable to appreciate grace, elegance and beauty.

It is not through science that we suck the marrow out of life and let it drip from our tongues like honey. Science does not allow you to live deliberately. It makes decisions for you. Settled facts leave no room for debate or dissent or individual interpretation.

It is through poetry, art and human interaction that our lives are validated. Civil society exists because somewhere, once upon a time, some group of people decided that looking after people’s safety and rights is important.

Despite the fact that, as a land-grant institution, Iowa State is charged, “without excluding other scientific or classical studies,” the teaching of “such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts,” there is a discrepancy between funding for and enrollment in hard and soft sciences.

In 2006, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences sent 40 percent of its budget to departments grouped as science and mathematics, which teaches 43 percent of student credit hours, employs 47.7 percent of faculty and has 22.5 percent of majors in the college.

The humanities and social sciences, meanwhile, receive 38.8 percent of the budget to teach 55.75 percent of student credit hours, employ 51.5 percent of faculty and teach 48 percent of the college’s majors.

People lived full experiences before science came along and provided us with modern conveniences. We are food for worms, and someday we will all fertilize daffodils. Technological and scientific progress will not save us from ourselves or from that fate. All too often, rationalism and science have provided the means to terrible ends.

The first world war was a boon to science. Using barbed wire, machine guns, flamethrowers, poison gas, airplanes, tanks, submarines and mines, vast armies entrenched themselves across northern France from Switzerland to the English Channel and wasted themselves on each other in four years of stalemated war.

Technology also served the second world war. The Holocaust brought 11 million people to their deaths through a progression of methods toward maximum efficiency. The Nazis improved their methods during a decade in power, moving from shooting people into mass graves to piping carbon monoxide exhaust into the back of sealed trucks before they reached their desired mechanism: the showerheads at Auschwitz.

The French Revolution’s solution to a world in which only reason was kosher, where religion and emotion had to be checked at the door, was a bloodbath. The 19th century’s reaction to a world in which science and its cold, hard, empirical facts would provide answers to everything was the medical phenomenon hysteria — the manifestation, especially in women, of real physical ailments with no apparent physical cause.

Finding a great key to everything in reason, even if it can be done, is impractical. The search drives men mad. Trying to reconcile problems using only reason also drives them mad. This problem does not belong only to the great mysteries of our time: Even chess players are afflicted with an obsession for finding the most perfect set of moves. Masters at the game, such as Paul Morphy, Aron Nimzowitsch and Bobby Fischer, exhibit patterns of descent into severe mental illnesses.

Experience formed by interaction with other humans is what makes life worth living. It is the soft sciences that give us civil society, morals and comfort in the face of injustice. Biological existence and the human experience are not the same thing. God’s only afterthought when he created the Garden of Eden was to create a second human, woman, because “for Adam there was not found a helper comparable to him.” The power to name each living creature was insufficient.

Life alone, even with complete dominion over nature, is no life at all: God created woman out of one of Adam’s ribs; by himself, he was incomplete.

Consider Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s character Sherlock Holmes. Intellectually brilliant, able to make use of the best logic and forensic analysis, he was sometimes a cocaine addict, regularly played the violin at 3 a.m. and was without friends or lovers. He cherry-picked through knowledge, learning only what was useful to him.

No one discipline is more important than another. Each is valuable in its own right. Science does nothing to alleviate the natural condition of man as one in which life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”