Belding: Compromise is an important part of American politics, the Constitution

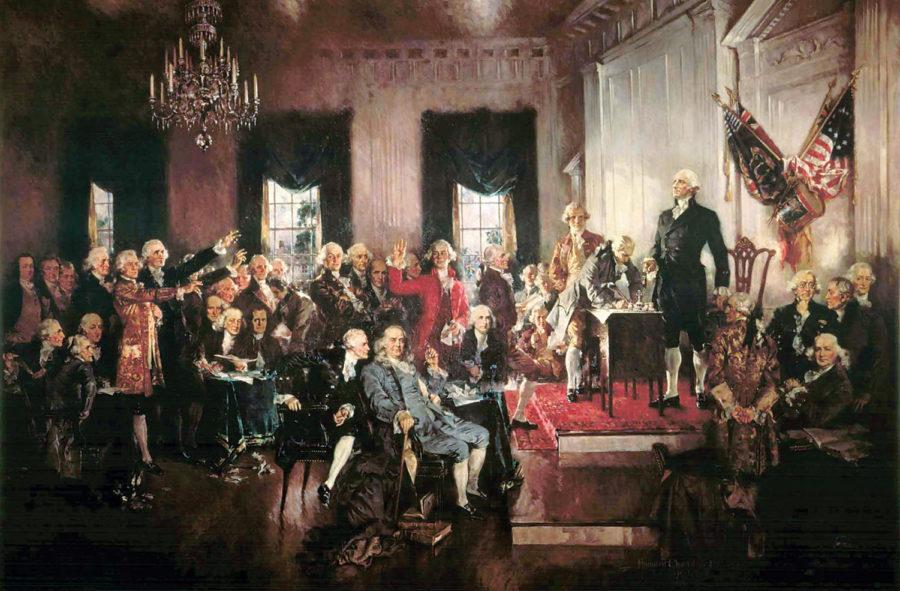

Courtesy photo: Wikimedia Commons

George Washington presides over the Constitutional Convention in this painting by Howard Chandler Christy.

April 12, 2011

The recent budgetary crisis of our federal government was resolved, temporarily, late last week. I am appalled that a shutdown of the government could have been both so acceptable to so many politicians, particularly those associated with the Tea Party, and so close to occurring.

It truly baffles me why Tea Party figures — who claim to love their country so much — are apparently so willing to see their government end. They actively campaign, in fact, for an almost nonexistent U.S. government.

This campaign is rooted in their belief that the Constitution commits the U.S. government an existence the size it was in 1790. But when we realize that the Constitution was formed as a series of compromises by realistic men, it becomes apparent that the Tea Party’s understanding of the Constitution as a binding policy vision is simply incorrect.

In his investigation into the economic influences bearing upon the delegates at the Constitutional Convention, Charles A. Beard commented on their character. They were, he wrote, practical men concerned with results; they had identified divisions within propertied, enfranchised classes that required resolution. The delegates were practical men “with actual economic advantages at stake.”

A study of The Federalist Papers, one of the most trusted commentaries — contemporary or otherwise — on the Constitution also demonstrates the compromising nature of the Constitution. John Jay, our first chief justice of the Supreme Court, identified the Constitution as a product of compromise in the second essay. The delegates, he wrote, made the Constitution “in cool, uninterrupted and daily consultation; without having been awed by power, or influenced by any passions except love for their country.”

Writing in the same set of essays on the subject of taxation, Alexander Hamilton wrote that the U.S. should have taxation powers concurrent with those of the states because “there ought to be a capacity to provide for future contingencies as they may happen; and as these are illimitable in their nature, so it is impossible safely to limit that capacity.”

The constitutions of civil governments should not, in other words, be made without regard to possible future needs. They should not be made to address only the immediate concerns of their makers.

Madison wrote a few essays later that the delegates to the convention needed to balance “the requisite stability and energy in government with the inviolable attention due to liberty and to the republican form.” This balancing purpose was the “object of their appointment,” and success in that object was “the expectation of the public.”

“The Convention,” Madison wrote, “must have been compelled to sacrifice theoretical propriety to the force of extraneous considerations.” One of his conclusions on the work of the Convention was that agreement was based on satisfaction and, additionally, “a deep conviction of the necessity of sacrificing private opinions and partial interests to the public good.”

My senior year of high school, I worked as a page in the Iowa House of Representatives. That year, 2008, was the year that body made smoking in restaurants and bars illegal. The House passed its version, and the Senate passed its version, as well. There were differences on which neither side wanted to agree. But one part of the debate of the House, on whether to accept the Senate’s changes or insist on its original, more ideal version, has stayed with me.

One of the Democrats, Rep. Philip Wise, stood up and advocated support of the Senate’s compromise bill by Democrats who wanted to reject it because it did not go far enough. The bill passed. That was Wise’s last year at the Capitol. His suggestion reminds us that, while pieces of legislation may not bring us into an ideal condition, they can certainly help us get there. Not adopting such legislation, in fact, continues the current broken condition.

The Constitution was one such instance of a compromise designed to move us toward a more ideal state of being. Madison wrote that “the choice must always be made, if not of the lesser evil, at least of the greater, not the perfect good.”

“The purest of human blessings,” he said, “must have a portion of alloy in them.”

It takes people, with their participation, to make any country work. Americans would exist without the U.S.; they would simply be under some other government. But the U.S. will cease to exist if Americans do not come out of their own little cupboards and open themselves to negotiation.

The Tea Party may very well achieve its goal of making the U.S. government smaller. But if they do so, it will have to be through convincing people that such policy is best. Such a goal cannot be imposed upon the minds of Americans. People will always disagree.

There is no one right answer.

If they want to give Americans the same opinion on politics and the Constitution without coming out into the open and participating in an exchange of dialogue, they will have to impose their opinions “by destroying the liberty which is essential to [their] existence … [or] by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions and the same interests.” Such was the observation, at least, of James Madison.

It is to compromise to which the U.S. Constitution is indebted for its existence. We ought to entertain the idea of bringing it into our politics a little more often.