Berch: Assange indictment is an attack on free press

Martina Haris, CNN Wire Service

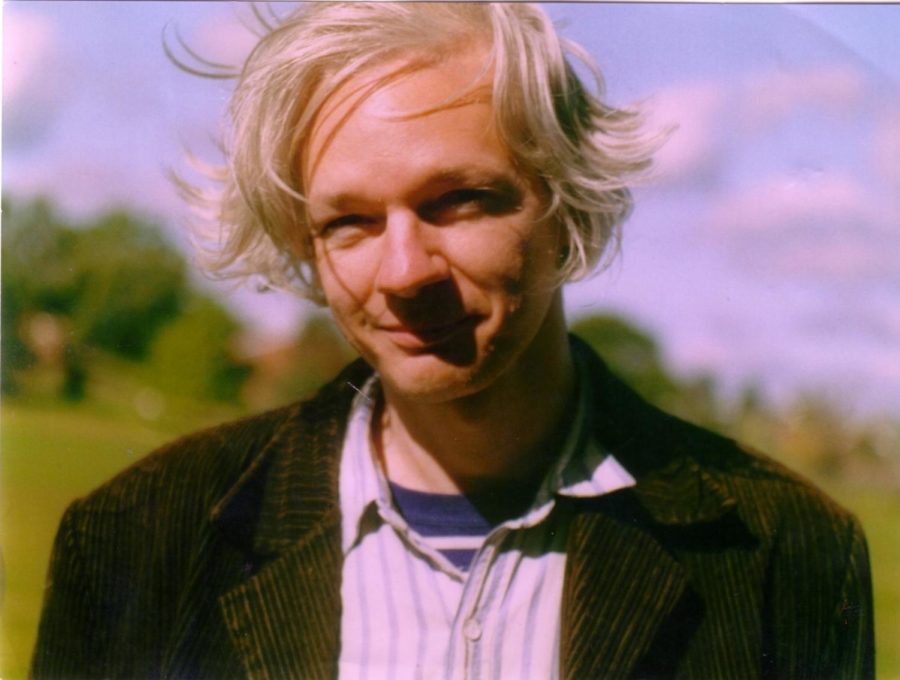

Julian Assange, editor-in-chief of the website WikiLeaks.

May 28, 2019

Julian Assange is a polarizing figure in both politics and journalism, but the charges levied against him under the Espionage Act last week take aim at an issue much greater than the WikiLeaks founder: freedom of the press.

The Justice Department has already begun to defend its indictment by saying Assange is “no journalist” but it has failed to explain how Assange’s work differs “in a legally meaningful way from ordinary national-security investigative journalism,” according to the New York Times.

Thus, we find ourselves at the real issue: should the government have the legal authority to punish people for the solicitation, receipt or publication of classified information of public concern?

Absolutely not.

Investigative journalism has undeniably shaped America’s history. Without the Pentagon Papers, Americans may have never known the full truth of our military involvement in Vietnam. Our only president to resign from office did so after reporters brought the Watergate scandal to light.

While many, including myself, would not label Assange as a journalist, the structure in the process is similar. As Carrie DeCell, an attorney for the Knight First Amendment Institute, wrote in a Twitter thread Thursday, much of what the Justice Department is laying out in its case against Assange is “exactly what good national security and investigative journalists do every day.”

Increasingly over the last decades, the Espionage Act has been used against domestic whistleblowers rather than foreign actors, with former CIA contractor Edward Snowden and former Army soldier Chelsea Manning both famously being charged in the last decade.

Now, the Trump administration has the opportunity to go a step past the Obama administration’s crackdown on the flow of information. Applying the Espionage Act to those who report on classified information would certainly reduce the number of reporters willing to take the risk of writing those stories. Had Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein been living in a world where such a precedent had been set, maybe President Richard Nixon would have completed his term in office.

Putting Assange at the front of a precedent-setting legal battle is a smart move by the Trump administration. Assange is not a palatable protagonist — late night host John Oliver once described him as someone “even Benedict Cumberbatch could not” make likeable. Many in both media and politics find him unappealing — he’s caused outrage on both ends of the political spectrum, he has a history of being careless in his redactions and he is currently facing possible extradition to Sweden for a rape charge.

But in the case of free press, he is becoming the unfortunate figurehead. Despite how one views Assange’s character, our views on the First Amendment and a free press must be prioritized, and we must support the larger issue at stake.