ISU students train dogs to assist blind

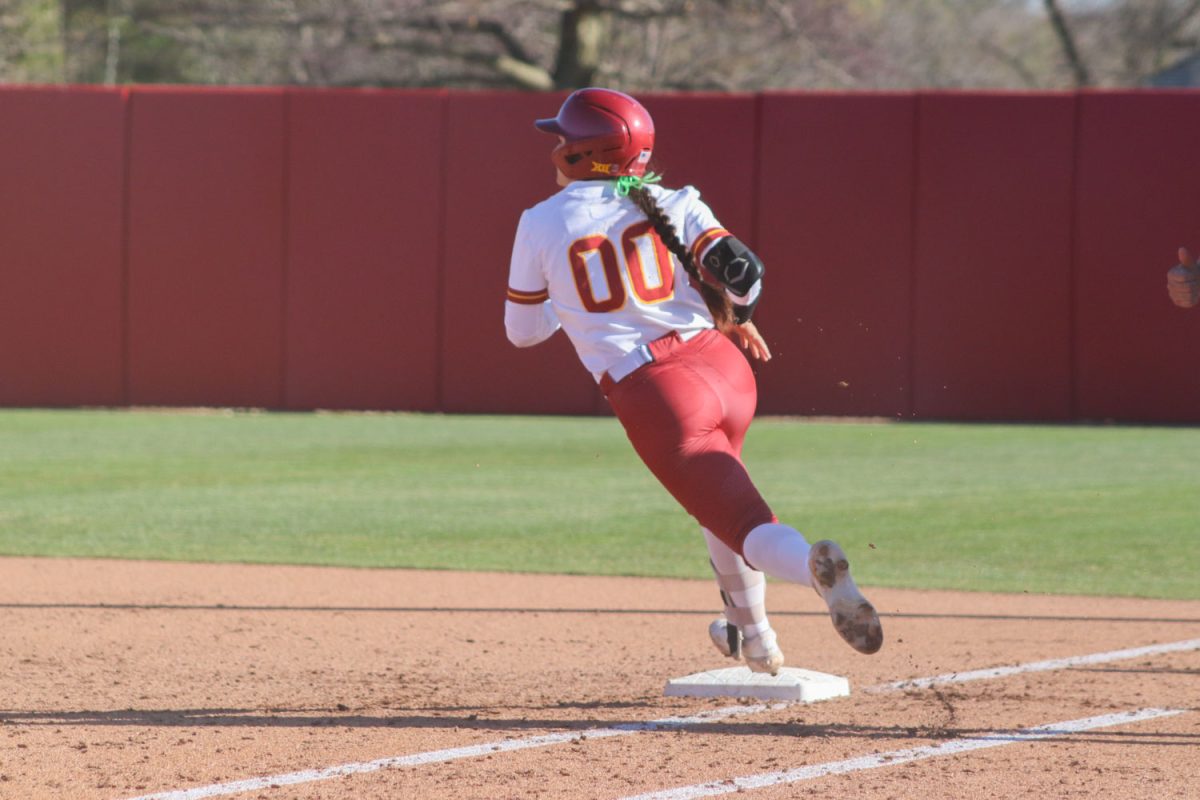

Photo: Karuna Ang/Iowa State Daily

Christopher Byrd, senior in animal science, trains Murphy, an 8-month-old Labrador, in preparation for Leader Dogs for the Blind.

March 7, 2011

ISU senior Jennie Huntrods takes her dog places most pet owners can’t.

Cora, her four-month-old German Shepherd-Labrador mix, attends classes with her, rides with her on buses and accompanies her in stores. People grant her this privilege because she’s preparing Cora to train with Leader Dogs for the Blind, a nonprofit organization that provides assistance animals to the disabled.

Huntrods is one of two ISU students currently raising puppies for the organization. She and fellow ISU senior Chris Byrd — who is raising an 8-month-old Labrador named Murphy — are just two of the hundreds of volunteers working with Leader Dogs in the U.S. and Canada. Both students hope their dogs will be among the 120 the organization donates to disabled owners every year.

The two dogs, however, can only be placed after they’ve proven themselves obedient enough to be trained at Leader Dogs for the Blind’s national headquarters in Rochester Hills, Mich. Volunteers like Huntrods and Byrd take the dogs in when they’re 8 weeks old and keep them for 12 to 15 months. During that time, the dogs are house-trained, taught basic commands and broken of habits that could disrupt a future owner’s daily routine.

While the dogs are in their care, volunteers attend monthly meetings with a “puppy counselor” who advises them on the best way to socialize their dogs. The counselor also holds a multi-site series of classes that allows dogs to get used to a variety of settings, ranging from private homes to prisons.

Byrd stresses that volunteers teach “minor things” like sitting, staying, heeling and moving clear of doors as their owners open them. But Huntrods thinks the overall rearing process serves a larger purpose.

“The main thing we teach them is just to be desensitized to their surroundings,” she said.

For future Leader Dogs, being properly desensitized means not responding to novel sights, smells or sounds the way an untrained dog would. To qualify for training, dogs must have the ability to sit still for long periods of time and walk among people without getting distracted by them.

Acquiring skills like these can be a difficult process for many dogs, and they seldom do so on the same schedule. Cora, for instance, is able to sit beside Huntrods for an entire class period without barking or stirring, while Murphy is still too restless to sit through class with Byrd.

If Cora and Murphy show enough promise as Leader Dog candidates, they’ll be sent to Rochester Hills around the time of their first birthdays. Once there, dogs train with instructors for five months. The first four are devoted to advanced skills such as avoiding obstacles and crossing busy streets. During their final month of training, they train with their future owners. These owners must be visually impaired to qualify for guide dogs, but they can also qualify if they suffer from both impaired vision and deafness.

As part of their training, dogs learn a crucial skill trainers call “intelligent disobedience” — the ability to recognize and disregard a command that would endanger their owners if followed. This allows them to keep their owners from doing things like walking into the path of an oncoming car or running into an obstacle.

Huntrods and Byrd know their dogs might not make it all the way to a disabled owner; some animals simply lack the temperament to serve the disabled. Those who don’t qualify as service dogs can end up staying with the volunteer who raised them. Others are adopted by a family. Still others become “therapy dogs” that provide affection and care to people in nursing homes and other institutions.

Regardless of where his dog ends up, Byrd is sure he won’t have any regrets about the time he spends with him.

“It’s kind of like gaining a friend,” Byrd said. “It’s really fun and rewarding at the same time.”