Brown: How old should a president be?

October 24, 2020

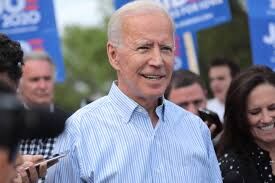

It’s been hard to ignore the obvious “oldness” of American politics lately. Donald Trump, the country’s oldest first-term president at 74, was born the year the bikini was invented. Joe Biden, the 77-year-old Democratic nominee, is older than the microwave. Bernie Sanders, 79, was born shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren, two of the highest-profile women candidates for president, were also born in the 1940s.

The aging of the presidency is especially important because America’s most visionary presidents have typically been young. Theodore Roosevelt, who became the youngest president ever at 43, had the foresight to preserve 230 million acres of public land for future generations to enjoy. John F. Kennedy, inaugurated at 43, supported the civil rights movement and started the Peace Corps to spread American values via young Americans. Barack Obama, who became president at 46, shielded young undocumented immigrants from deportation and committed to the Paris Climate Agreement, aimed at preserving the planet for years to come.

The youngest presidents tended to think more clearly about policies that would benefit future generations and were less likely to have long-standing prejudices.

So when it comes to making tough calls in politics, does older really mean wiser?

Probably not. Older adults can get stuck in their ways, be too confident in their own opinions and ignore new facts that alter them. In the 1960s and 1970s, presidents would bring in elder advisers to give them counsel during times of crisis. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, President John F. Kennedy brought former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, 68 at the time, into his group of advisers. Acheson counseled the young president to take out the Soviet missiles with airstrikes. It’s a good thing Kennedy did not listen to Acheson or it might have escalated into nuclear war.

Older adults also get physically and mentally drained, no matter how hard they have to stay healthy and alert. In his mid-70s, President Ronald Reagan may have suffered from early dementia by the end of his second term. By the end of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s second term, he was spending more time golfing than dealing with the escalating arms race or the secret excess of the CIA.

Not listening to new and fresh perspectives can also have horrible consequences. During the Pacific War in 1945, Henry Stimson was President Harry Truman’s top civilian adviser and secretary of war. At the time, 77-year-old Stimson argued for dropping the atomic bomb on Japan.

His 40-year-old aide, John McCloy, attempted to argue that “we ought to have our heads examined” if the United States didn’t try to induce the Japanese to surrender before dropping the bomb. McCloy suggested that instead of demanding unconditional surrender, the Allies should let Japan keep its emperor, which might have worked to avert the explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Unfortunately, no one listened to McCloy, who was deemed too young and brash.

We do not need to be voting for older adults just because they are old. If Americans can’t elect a new generation of young leaders, established leaders are simply sticking around and aging in place, with nobody left to replace them.