Shiralkar: Skating for Godot

October 25, 2020

After World War II, an absurdist movement took root and subsequently bloomed within arts communities across Europe. As artists sought out meaning in the wake of wretched destruction, the absurdists attacked the existing perceptions of language — existence itself, even — through their work. “Waiting for Godot” (1953) is a Vaudevillian-style play written by Samuel Beckett, former soldier and Literary Nobel Prize winner. Like its contemporary works, “Waiting for Godot” sheds light on the bleak nature of the human condition, with a bit of humor and a bit of song and dance, just to take the edges off.

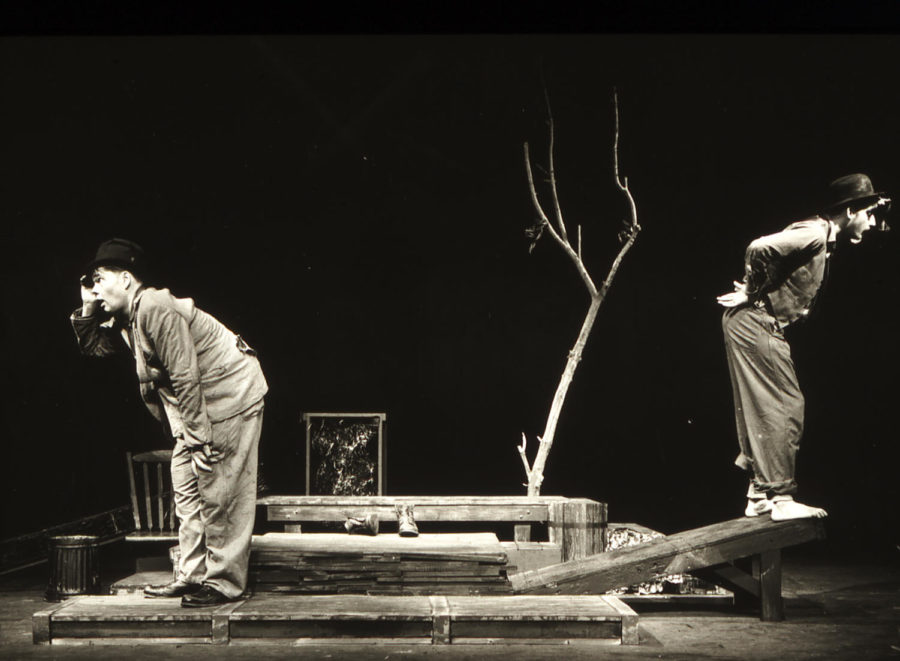

The play starts off with Estragon, a shabbily dressed man, struggling to take his boot off near a tree at dusk. He is soon joined by his friend Vladimir, who reminds Estragon about the person they’re supposed to wait for: Godot. The rest of the play unfurls in a repetitive yet engaging debate — one that seeks to answer questions about Godot, contemplations of suicide, whether they’re at the right tree and if Godot even exists. “Nothing to be done,” a repeating phrase throughout, does a nice job of setting the theme.

The play still receives mixed reviews, but its impact on the landscape of modern drama cannot be ignored. With its revolutionary style, coupled with bits of dark comedy peppered and satirical commentary about existential subject matter, “Waiting for Godot” was one of the absurdist movement’s most influential works of art. Beckett’s writing has an unusual tempo, with lapses in dialogue and then frantic, motion-based interactions. He called the play “a tragicomedy in two acts.” And a tragicomedy in two acts it is.

Vladimir and Estragon consistently engage in some of the other physical comedy bit during the play. Dressed in bowler hats and boots, they pace the dialogue in the likeness of a well-rehearsed comedy skit. While the characters tackle questions about the meaning of life, death and religion, their interactions are pedestrian, circular and, indeed, lined with banter. It shouldn’t work as well as it does; the second act is a near-replica of the first, signifying the cyclical structure of the play. There is no climax, in mostly the same way that there is no plot.

In a way, Beckett taunts the audience with this repetitive dialogue assembly. By the time the reader gets to the second act, a strange feeling blossoms inside the audience’s minds. What are we doing, if not the exact same thing Estragon and Vladimir are doing? We’re waiting for an unseen force to compel us into action, while we live the same day over and over, with just minor changes in the same routine. This subtle mockery of the commoner’s lifestyle is what makes “Waiting for Godot” an important literary piece.

Vladimir and Estragon are stuck in a paradox of their own creation — they wait for an unknown character to give them purpose, and yet their only sense of purpose comes from the very act of waiting. Beckett eventually pulled the “mysterious, enigmatic playwright” card and left the meaning of the play open to interpretation. While reading the play, it is uncertain, at times, whether laughing or crying would be an appropriate reaction. Especially now, when life is perhaps at its most nonsensical, works like “Waiting for Godot” are a welcome respite from reality. It’s a pretty short read, too. Wash your hands and wear a mask.