Research suggests STEM gap begins in middle school

October 1, 2020

The STEM gap persists at the collegiate level, but psychology and philosophy researchers found the STEM gap starts in upper elementary and middle schools.

Even with an emphasis on gender equality in STEM fields — science, technology, engineering and math — the gap between men and women in STEM has persisted. This is known as the STEM gap.

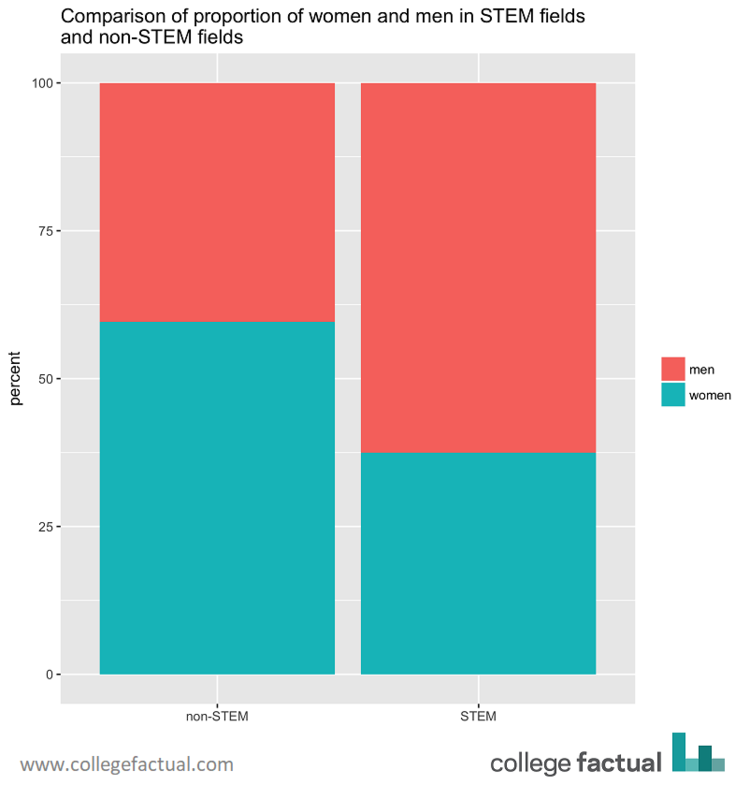

According to USA Facts, women make up 32.1 percent of all STEM degree recipients, an increase since 2009. However, men increased their STEM involvement faster than women, maintaining the STEM gap.

Since the STEM gap is already apparent at the collegiate level, scientists are now examining the possibility that elementary schools could impact the STEM gap.

Carlie Trott, psychology professor at Cincinnati University, and Andrea Weinberg, philosophy professor at Arizona State University, mention that upper elementary into middle school is very important for girls’ STEM confidence.

Trott and Weinberg published their research titled Science Education for Sustainability: Strengthening Children’s Science Engagement through Climate Change Learning and Action in August 2020.

“Upper elementary and early middle school is a critical stage for girls’ science interest and confidence,” they wrote.

Bryan Hughes, a STEM teacher for fourth and fifth graders at Lakewood Elementary School, said girls and boys in his classroom are equally interested in learning about science. They cover a variety of topics from robots to germs.

“Girls get into [science] just as much as the boys do and vice versa,” Hughes said. “The girls are just as fired up about science as the boys are.”

Hughes said he recognizes how important it is to continue to encourage girls to pursue science and STEM.

“Girls are absolutely as good at science as boys. One hundred and ten percent,” he said.

This concurs with Trott and Weinberg’s research, supporting the hypothesis that the STEM gap begins in middle school.

“From early adolescence, girls express less interest in the math and science careers compared to boys, with gender differences in STEM self-confidence beginning to emerge in middle school,” they wrote.

Kristin Merkle, a teacher at Horizon Elementary School, said she has noticed positive changes within her classroom because of STEM in the past five years, and fifth grade girls are confident in their discussions.

“I think there have been more opportunities for girls to participate in STEM activities,” she said. “[Girls] in fact seem more focused and creative on the tasks than the fifth grade boys.”

According to The Atlantic, girls score just as well as boys in science-related tests across the world.

“In almost all countries, girls would have been capable of college-level science and math classes if they had enrolled in them,” Olga Khazan wrote.

This leads scientists to believe the STEM gap is not because of an aptitude problem, but a systematic problem. More scientists are now conducting research on how the STEM gap forms and why it exists.

Annika Duitscher, Iowa State freshman in biology, said women should continue to pursue STEM-related careers despite the STEM gap.

“We need people in STEM careers,” she said. “Why shouldn’t they be women?”