Brown: The protesting power of moms

July 27, 2020

When mothers protest and take to the streets over political issues, particularly from those more privileged, governments tend to take notice. The “Wall of Moms” in Portland, Oregon, has taken up the cause against police violence. They follow a long line of other mothers who have used their privilege to stand up for others.

Portland’s protests have begun to change two months after a group called the “Wall of Moms,” (self-identified mothers) who have converted chants into lullabies at protests to form human shields between federal officers and protesters.

Beverley Barnum, one of the original organizers behind Wall of Moms, asked women to color coordinate their outfits in order to stand out in the crowd, but otherwise told them to dress “like they were going to Target.”

“I wanted us to look like moms,” Barnum said in an interview. “Because who wants to shoot a mom? No one.”

That didn’t stop federal officers from showing force to the line of mothers protesting in downtown Portland. While they had set out to keep the peace, they were caught in the crossfire and were tear gassed by police.

“The feds came out of the building, they walked slowly, assembled themselves and started shooting,” Barnum said. “I couldn’t believe it was happening. Traumatic doesn’t even begin to describe it.”

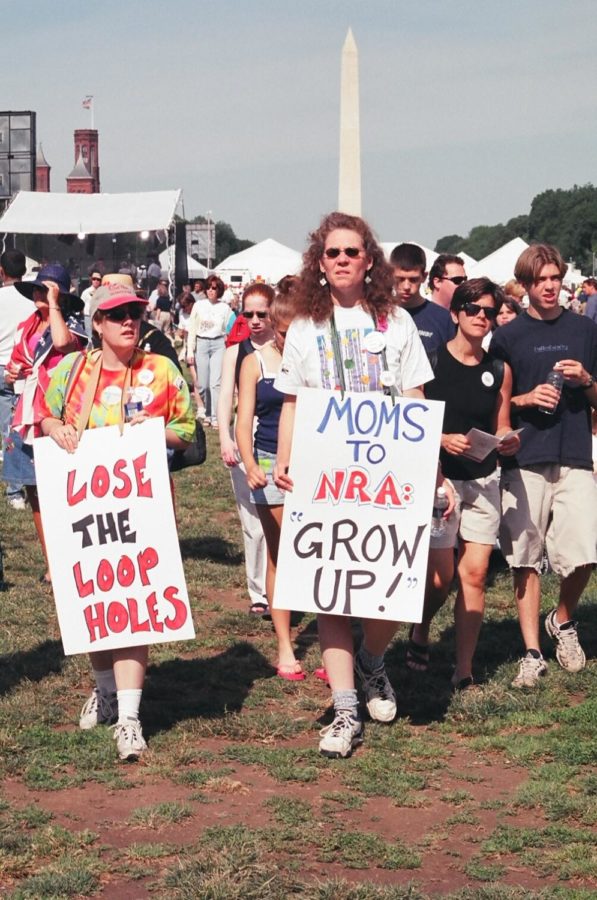

The Wall of Moms joins a long line of mothers’ protests around the world against state violence and what they view as authoritarianism, showing that mothers can be particularly effective advocates for a cause. Mothers’ protests are often powerful because gender roles that ordinarily silence and sideline women allow them to be seen as nonthreatening. This turns them into an armory for political activism.

During Armenia’s 2018 “velvet revolution,” a largely nonviolent uprising that eventually toppled the country’s leader, Serzh Sargsyan, mothers took to the streets pushing their children in strollers, tying their maternal identities to their political demands.

In Armenia, “mothers are symbolic to the nation, and to some extent, have immunity in protests,” said Ulrike Ziemer, a sociologist at the University of Winchester in Britain. “If police would have touched mothers with their children during the protests, that would have brought shame on them individually, but also on the state apparatus they represent.”

In the Armenian protests, mothers from all walks of life were able to claim these protections. In societies divided along racial or ethnic lines, however, mothers from marginalized groups cannot access that full political power so easily.

History suggests mothers’ power is most potent when they are able to wield their own respectability, and the projection it brings, as a political weapon. However, this is easier for women who are already married, affluent and members of the dominant racial or ethnic group.

Mothers who are less privileged often struggle to claim that respectability and power, even though they are often the ones who need it most.

There are obvious differences between Armenia and the United States. However, Ann Gregory, a Portland mother who joined demonstrations, was deeply disrupted by the federal officers’ violent response to the protest.

“We weren’t any danger to them,” Gregory said. “We were just standing there with flowers. We are a bunch of middle-aged moms.”

Mothers hold up families, and these instincts are one of the reasons the Black Lives Matter movement has caught fire in suburban communities. As long as there will be sons and daughters dying due to police violence in America, mothers will be at the front lines, fighting for the lives of their children.