A look into China’s rapidly growing economy and its ability to rival the number one U.S. economy

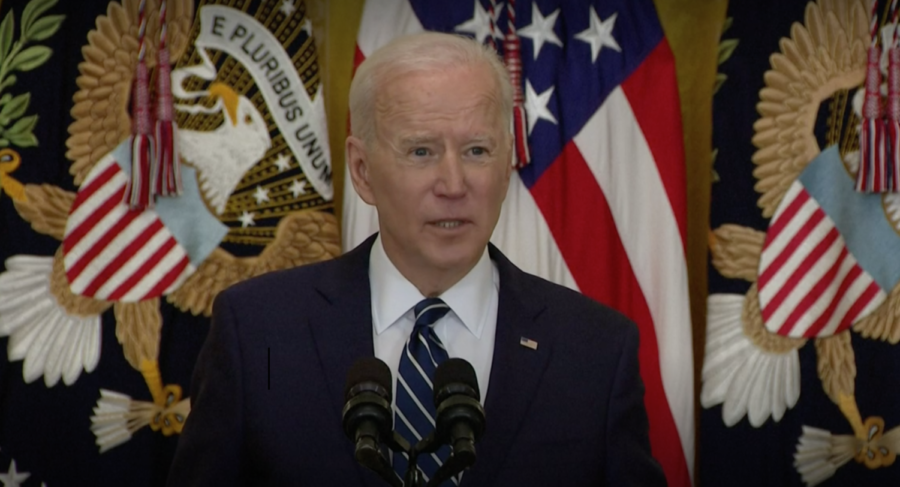

President Joe Biden discussed China as a rising economic competitor to the United States during a press conference.

April 8, 2021

China’s economy is the second largest in the world, posed to become the largest and surpass the U.S. economy as the global economic leader.

In response, President Joe Biden has promised intense competition and vowed that China will not pass the U.S. as the global economic leader.

But despite growth in recent years, China’s economy has not always been the global economic powerhouse it is today.

A brief history of U.S. and Chinese economic relations

Under Mao Zedong’s leadership from 1949 until the late 1970s, China experienced extreme economic and political isolation from the rest of the world. Outside of a little limited trading with Hong Kong, China and the United States were not interactive with each other.

The United States’ ties to China began in 1972 with President Richard Nixion’s visit to China to establish the Shanghai Communique, an agreement between China and the United States that, in global interest of all countries, agreed to normalize their relationship.

Zedong’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, made the decision to open China up to global investment in 1979 and to focus on “The Four Modernizations”: agriculture, industry, military and science and technology.

James McCormick, professor of political science, said in an email that this change in China’s economic policy is when China and the United States’ economies started to interact.

“Development took off with Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, the successor to Mao, with his decision to open up the Chinese economy to outside investment and to focus on the Four Modernizations,” McCormick said. “American companies and other nations’ companies saw important investment opportunities with Deng’s decision.”

What caused China’s economic boom

Since China’s introduction to the global economy in the 1980s, it has seen unprecedented economic growth, averaging a 10 percent growth in gross domestic product every year since.

“After China became more open to outside investment and development, it became the factory — the manufacturing factory for many consumer goods — for much of the world with a low-cost wage environment, substantial external investment and the rapid expansion of exports to the rest of the world,” McCormick said.

The World Trade Organization reported in 2019 that China exported just under $2.5 trillion worth of global goods as the world’s largest exporter.

The governing body of China, the Chinese Communist Party, still holds substantial stakes in the private sectors of the market but has helped gradually spur economic growth, said Jonathan Hassid, associate professor of political science.

“The Chinese Communist Party has gradually liberalized many sectors of the economy rather than doing it all at once, and this gradual pace of reform has proven helpful in spurring economic growth compared with countries like Russia that liberalized overnight,” Hassid said.

The U.S. and China today

China’s labor market is a major contributor to their economic gain. With low wages and the ability to produce goods for less, China became a honeypot for global investors and challenged the U.S. labor market.

“Since China had a low-wage environment and could produce goods cheaply, many investors, including many from the U.S., moved operations there, oftentimes at the expense of manufacturing in the U.S.,” McCormick said. “As a result, growth rates in China reached double digits and remain in high single digits in its economy.”

Hassid said the difference in industry and service-based economies play a role.

“China has a large internationally oriented manufacturing sector and a much smaller service sector than the U.S.,” Hassid said. “China is likely to overtake the U.S. as the world’s largest economy by the end of this decade, though the country will still be much poorer per capita than the U.S.”

Hassid also said one reason China’s growth is substantial compared to the U.S. is that China is a much poorer country, making large economic growth easier.

“U.S. economic growth has been slower than China’s in large part because the U.S. is already rich and China is not,” Hassid said. “Although any economic growth is hard to achieve, it is much easier for a poor country to grow rapidly than a rich one.”

As for what changes the U.S. can make, both Hassid and McCormick said the U.S. needs to invest more into the private technology sector.

“One of the biggest challenges for the U.S. is that it must be able to continue to highlight its advantage in innovation and in the technology sector,” McCormick said. “Certainly, China has now committed to innovation and technology at a rapid pace, so the United States faces a real challenge there.”

Currently, the U.S. is allowing the free private technology sector to provide in response to the technology development in the East rather than nationalize the industry.

“I do think it would be helpful for the U.S. to have a national industrial strategy like the country did in the early days of the Cold War,” Hassid said. “Certain sectors of the economy — robotics, artificial intelligence, digital currencies, quantum computing and the like — are worthy of state investment. China is pouring billions into these emerging fields, and the U.S. should not rely solely on the private sector to respond.”

McCormick said this lack of funding and research by the U.S. is an issue of concern for a future merging of the public and private technology sectors.

“If the U.S. can continue to hold an edge in this area and create a more stable and unified domestic environment; it will be able to compete,” McCormick said.