Systematic and interpersonal issues with colorism

March 5, 2021

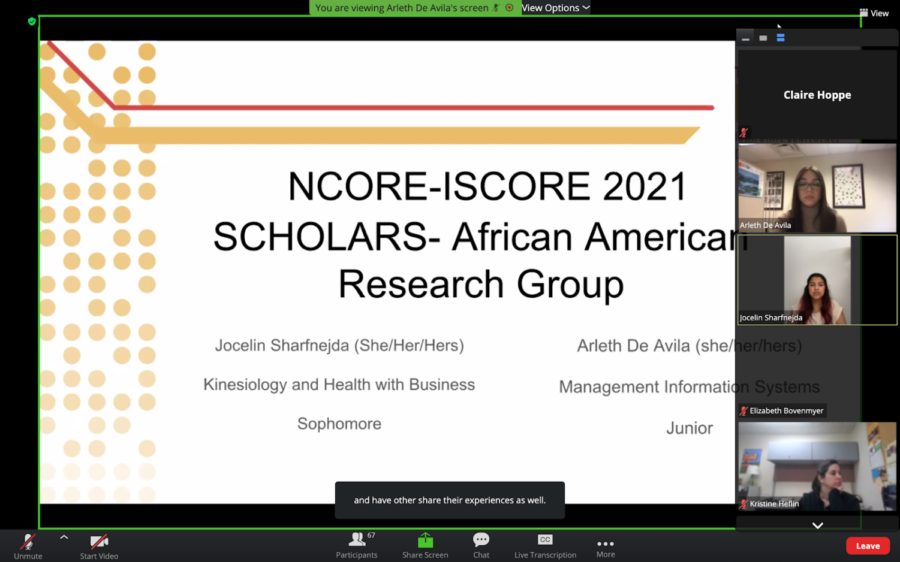

Two Iowa State students shared a presentation titled “African American ‘My black is beautiful’: A Discussion on How Colorism Impacts Black Women within the Black Community” at the Iowa State Conference on Race and Ethnicity (ISCORE).

Arleth De Avila, a junior is management information systems, and Jocelin Sharfnejda, a sophomore in kinesiology and health with business, began the virtual presentation by defining what colorism is — the discrimination of someone based on someone’s skin color or shade. They also said colorism manifests both interpersonally and systematically.

De Avila and Sharfnejda then described how colorism has come to be so strongly rooted in America. According to them, colorism began as early as 1679 when slave owners made their darker-skinned slaves believe they were inferior to the lighter-skinned slaves. This happened by slave owners giving preference to the slaves that more closely resembled a white skin color while darker-skinned slaves were left to believe they were not as smart or as valuable as their lighter counterparts.

The conversation then moved to the difference between racism and colorism. According to De Avila and Sharfnejda, colorism is a symptom of racism. For example, De Avila and Sharfnejda said that while enduring racism, those of the same race will be treated equally, but when people of the same race endure colorism, they will be treated unequally.

The co-hosts then went into detail on five different ways African American women are affected by colorism: in their personal experiences, higher education, the workplace, health care and the justice system.

As for how Black women are affected by colorism in their own personal experiences, De Avila and Sharfnejda discussed how darker-skinned women feel less attractive and have lower self-esteem than their lighter-skinned counterparts. This is partially due to the fact that darker bodies have consistently been devalued throughout history by the government, media and even by families.

Secondly, according to De Avila and Sharfnejda, Black women are affected by colorism in higher education by being less likely to graduate with a degree in six years and by continually being underrepresented in universities across the country. In the presentation, Sharfnejda said research shows only 5.2 percent of faculty members at universities are Black.

According to De Avila, Black women have been the most educated and undervalued employees in the workplace. For example, De Avila referenced Matthew Harrison by saying Black women who are more educated are less likely to get a job than white women who are not as educated. Not only that, but Black women also experience microaggressions, comments and actions that demean or dismiss someone based on their gender, race or other aspects of their identity. Due to these comments, Black women are more likely to feel disrespected and feel the pressure to look more European.

As for health care disparities Black women face due to colorism, De Avila said Black women are more likely to experience stressors and discrimination that affect their mental health and cause depression than their lighter-skinned and white counterparts. De Avila also said that while Black women are more likely to be denied medical treatments due to personal biases, they are also three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy challenges, which in many cases can be treated.

Lastly, Sharfnejda focused on how Black women are affected by colorism in the justice system. She discussed how lighter-toned women receive 12 percent less time behind bars for a punishment compared to darker-skinned women and how young, Black women are three times as likely to be imprisoned compared to young, white women. She also said darker-toned women were 11 times more likely to experience discrimination while being imprisoned than lighter-skinned women.

De Avila and Sharfnejda reminded the audience to continue to listen to all women of color and to make space for all Black women in every part of life.