Moving past white fragility: An ISCORE presentation

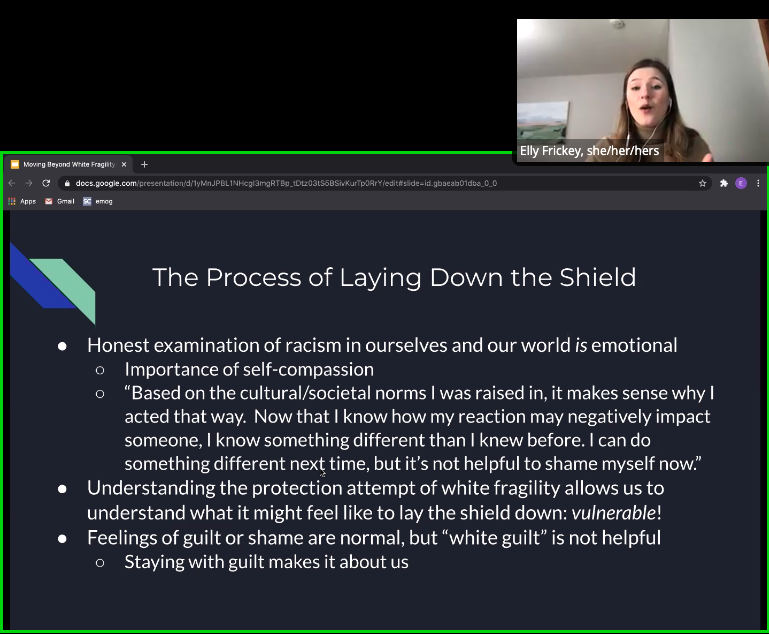

Elise Frickey presents a slide about laying down the false shield of white fragility and what white people should do to become better allies to BIPOC.

March 4, 2021

During the virtual Iowa State Conference on Race and Ethnicity (ISCORE), two Iowa State staff members presented about white fragility and how using metaphor, cultural humility, self-compassion and action steps can move those that identify as white past fragility.

Elise Frickey, a graduate assistant in Career Exploration Services, and Erin Pederson, a staff psychologist at Student Counseling Services, gave a presentation titled “Moving Beyond White Fragility: Function, Metaphor, and Growth.”

The session opened with Frickey and Pederson acknowledging their privilege of identifying as white, cisgender women in the Midwest.

Frickey and Pederson then led into the definition of white fragility that they would be using in their presentation.

“White fragility has been defined as low stamina to handle racial stress in conversations or situations and reacting with defensive moves to avoid or diminish the focus on race or racism,” Pederson said.

They touched on how white fragility has been taught and reinforced by many of the larger systems in the United States, including but not limited to the public education system, the policing system and the criminal justice system.

“Having to do hard work, learning, educating ourselves, challenging ourselves and having real conversations [about race] is hard, and it’s something that [white people] have been protected from,” Frickey said.

Frickey and Pederson described white fragility as a sort of shield. When the shield of white fragility is taken away, white people feel very vulnerable to the reality of benefitting from systems that oppress Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC).

“White fragility in a way serves to keep us safe,” Frickey said. “But the sense of safety is really an inauthentic kind of ignorance that is ultimately very damaging.”

The presenters talked about several different ways white fragility can show up in conversations. They discussed changing the subject, avoiding places that could increase the likelihood of talking about race and focusing on marginalized identities. The last two the presenters discussed were defensiveness and emotional intensity.

“Emotions aren’t inherently bad,” Pederson said. “The problematic part of this is when the energy of the conversation, the focus of the conversation gets pulled towards the emotions by either responding to it or taking care of the emotions.”

Pederson and Frickey discussed their own personal anti-racism journeys and their own white fragility. They shared personal examples of times when white fragility impacted their actions and thoughts and shared some ideas for how to change the mindset.

They encouraged action steps and goals for the next day, week and month. They also encouraged participants to find an accountability partner to help keep them accountable to their goals.

Frickey shared her goals, saying, “I need to be willing to be uncomfortable. BIPOC folx have been uncomfortable with white people in conversations about race for a long time and continue to be from the behaviors that we are engaging in, so I need to be willing to step back and to sit in some of that discomfort myself.”

She also touched on the fact that the anger and pain many BIPOC folx feel is justified.

“I need to be willing to do the work myself,” she said. “I’m not asking BIPOC folx to do the work for me, but to educate myself and to listen to their voices. I need to be willing to value impact over intent.”

Pederson and Frickey closed the presentation by sharing resources that can help educate people on white fragility.

“Educate yourself by learning how the systems we reside in have been designed to oppress people of color and to benefit white people, and then how when a law is taken away or changed a policy or practice continues on,” Pederson said. “Identify how your impact trickles down.”