An opportunity to be normal

April 16, 2018

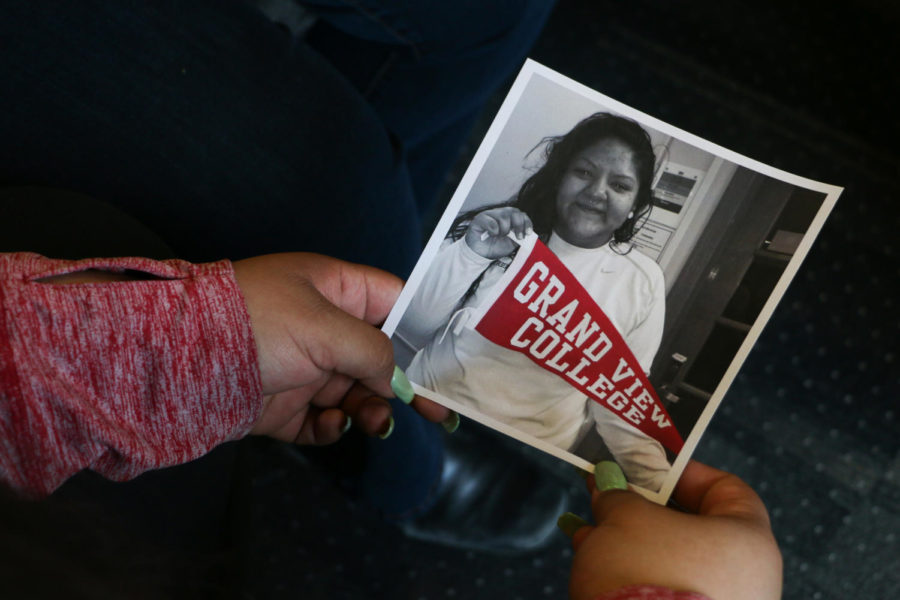

March 3, 2015, would go down as the best day of Giselle Sancen Valero’s life.

It was 35 degrees and rainy, she remembers. It was her senior year of high school.

She was on her way back to Lincoln High School in Des Moines from lunch to finish her final two classes of the day. As she stepped into her car, her phone rang. She saw that it was a 515 number — the area code serving north-central Iowa — so she immediately answered.

She had been expecting a call from Grand View University to confirm whether she had received the Immigrant Iowan Scholarship.

“Hello?”

“Hi Giselle, this is Amy from Grand View … ” Giselle remembers her not sounding particularly happy.

“Yes, hello.”

“I’m sorry, I just wanted to let you know …”

Great, Giselle thought.

“…That you got the scholarship and I’m so sorry it’s taken me so long to reach you!”

Giselle immediately began crying.

“You almost made me have a panic attack, thank you so much!” She could hear other admissions counselors in the background cheering. “OK, I gotta go because I’m going to be late for my next period.”

At this point, Giselle was soaked — from tears and from the rain. She could barely see the road. Surely I’m going to crash my car, she thought.

By the time Giselle pulled into the parking lot, she didn’t have time to try to find an open space. She needed to tell her counselor, Laurie Butz, as soon as possible. She didn’t think twice about parking in the vice principal’s spot.

She sprinted inside, still bawling. She ran past the security officer and the vice principal.

“I parked in your spot. I’ll move in a second,” she yelled between her sobs. Of course, no one could understand her.

After weaving her way through the crowds, dismissing the “are you OK” comments, she eventually reached Laurie’s office, out of breath with mascara streaking down her face.

“Oh no, honey, what’s wrong?” Laurie asked. She began consoling Giselle, thinking she didn’t get the scholarship. “It’s going to be fine.”

“No, I got it. I got it!” Giselle said, eventually.

At this point, the vice principal, principal and security officer had caught up to her and found Laurie and Giselle in a tearful embrace. They joined in.

Everyone knew how much was on the line for Giselle. If she hadn’t received the scholarship, she wouldn’t have been able to go to college for a long time.

I will never be sad again, she thought.

Growing up

Giselle was born in Mexico City, Mexico, in 1996. At age 2, her parents made the decision to pack up and head for the United States for a reason that most other immigrants share: to have a better life.

Giselle’s family had heard that Iowa had opportunities for good jobs and was safe.

Her dad applied for a visa and left for the States, purposely leaving Giselle and his wife behind. He wanted to get a stable job, have a car and apartment ready before his family would arrive.

A year-and-a-half later when Giselle’s dad was ready, Giselle’s mom strapped her to her back and made the trek from Mexico City to Iowa, wading across the Rio Grande, walking across the border and hopping into a caravan full of other immigrants heading for the Midwest.

While Giselle doesn’t remember a lot from her early childhood, she remembers the difficulties of learning to speak Spanish at home and English at school. She occasionally would mix her words together, sounding like a “Spanglish slur.”

“I’d come home crying every single day because kids would tell me I spoke like an alien or I wasn’t from here,” she said. “That was really the first time I realized I was different.”

The teasing and taunting continued through middle school, but one particular incident stuck with her.

It was in seventh grade. Giselle and another boy were arguing over a math problem. The boy insisted he was right, but everyone else at the table agreed that Giselle’s solution and explanation seemed most correct.

The boy still wasn’t having it, Giselle remembers.

“You guys are supposed to agree with me,” the boy said. “Giselle doesn’t even know what she’s talking about; she barely speaks English.”

However, Giselle had lost her accent and spoke English proficiently by this point.

“But it doesn’t even matter, because even if you are right, when we grow up, you’re just going to be cleaning my house and you’re not going to need to know how to solve this problem anyways,” the boy said.

Giselle stood up and flipped the table.

“You’re just mad that I can speak two languages and you can barely speak one,” she responded.

“It was the first time that I was awakened to the fact that the color of my skin and my background was a thing that was going to label me for the rest of my life,” Giselle said.

‘Angry Latina’

At age 12, Giselle witnessed her father being deported to Mexico after failing to appear in court to pay the fine for running a red light.

Giselle’s mom, Laura, was left with the responsibilities of raising Giselle and her brother by herself and paying for everything for five years. They sold one of their cars and began renting out their basement.

Right before Giselle’s senior year of high school, Laura began dating again.

“It was so weird to see, but I was happy because she was happy for the first time,” Giselle said.

Laura eventually remarried the man who “became a big part of our lives.”

But less than three years into their marriage and just under a year after Giselle arrived at college, Giselle’s stepfather grew sick and needed a liver transplant.

Because he was undocumented, he didn’t have insurance. No hospital would take him in and no surgeon would operate on him. Giselle started a petition on July 10, 2016, to cover the $30,000 it would take to fly him back to Mexico to seek treatment. But it wasn’t enough.

Nine days later, he died.

“I felt that it was such an injustice that because this man was born on the wrong side of the border or didn’t have a piece of paper, his life was just kind of thrown away when it should have been a very simple procedure,” Giselle said. “At that point, it was really when it clicked that the community that we lived in and the world that we lived in is so unjust and unfair … and there’s really nothing we can do about it, at least not as a 20-year-old.”

Paying for college

Giselle originally wanted to attend Iowa State University, but she realized that she wasn’t eligible for the Multicultural Vision Program award — a full-tuition scholarship to non-white residents of Iowa — because she wasn’t a U.S. citizen and couldn’t file the Federal Application For Student Aid, FAFSA.

“That kind of hurt me a lot more than it should have. … Again, I was told that I didn’t belong here and this wasn’t my home, and I’ve just been kinda chilling here for 16 years for no reason,” Giselle said.

She then turned to private schools out of frustration and found Grand View to be the perfect fit.

Out of the three other private schools she toured in central Iowa, Grand View was the only one that offered a scholarship of its size, Giselle said.

Laurie helped her track down the scholarship and made her come in for 30 minutes every day to work on it.

The scholarship application asked for a 500-word essay and two letters of recommendation, Giselle said.

She wrote 1,034 words and submitted 13 letters.

So when she found out she got it, she felt as though a weight had been lifted off her shoulders. She wouldn’t have to worry about paying the $36,506 — the comprehensive cost of attending Grand View — in its entirety.

But while the Immigrant Iowan scholarship covered her tuition and room, Giselle still had to pay for her food and books, which totaled just under $4,000 per year.

She picked up another job — in addition to already working at the Boys and Girls Club — at Sprint to help. In all, she was working about 30 hours per week.

“Working part-time [jobs], it was not easy to get that kind of money and pay for gas to get to my [jobs], but I did it,” Giselle said.

Giselle took out a $1,000 loan from her credit union. As a DACA recipient, she’s not able to take out student loans.

“I think the thing that frustrated me the most is that I was so financially unstable. Everybody’s like, ‘I’m a broke college student,’ but I was broke,” Giselle said.

Giselle never went hungry, per se — she was paying for a 5-Day All Access meal plan, which provided unlimited, all-you-can-eat meals Monday through Friday. But when the dining room closed at 8 p.m., she didn’t have any foods to snack on. So if she was hungry, she would go to bed hungry. On weekends, Giselle had the luxury of going home, where she knew there would always be food, even if it was just rice or eggs.

But Giselle never lost sight of the opportunities that the scholarship gave her, citing it as the biggest blessing of her life.

“I really don’t know what I would do if I had to pay out of pocket for actual classes or credits, and I try to not overlook that. I always complain [that] I don’t have any money. But I’m getting a degree that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars, so I try to just stay positive as I can and I take advantage of all the resources I have,” Giselle said.

Mental health

By her sophomore year of college, Giselle’s mental health was, as she described, a roller coaster. But she didn’t recognize that she was suffering.

Her parents raised her with the idea that mental illness isn’t real.

It’s not a mental thing, you’re just sad.

It’s not a mental thing, you’re just lazy.

It’s not a mental thing, you just want to give up.

“I kept repeating that to myself when I was in fact severely depressed … because that’s how I was raised — to internalize everything,” Giselle said.

Giselle hadn’t had time to process her stepfather’s death. She took it upon herself to plan the funeral, fly her step-grandmother into the United States, gather friends and family for the funeral and figure out the finances — all so her mother could have time to grieve.

She wasn’t able to properly feed herself and sustain herself.

And if that wasn’t enough, she was swept up in typical underclassmen concerns — finding a good group of friends, activities to get involved in and adjusting to college.

“I feel like every college student already is on the verge of a mental breakdown,” Giselle said. “Add being a person of color, add [coming from] a single parent [household], add not being financially stable, add just the injustices of our communities, it becomes a lot and it’s a lot to carry.”

She began to miss classes and fall behind on her schoolwork, all while working 30 hours a week. She didn’t want to get out of bed in the morning anymore. She was constantly exhausted and sore.

“There were days when I was like, what am I doing, what if I just dropped out, what if I just went back to Mexico,” Giselle said. “I felt like what I was doing wasn’t worth the amount of effort that I had to put in.

Her roommate began to notice.

One morning, Giselle woke up to a wardrobe full of positive sticky notes with phrases like “you are allowed to be both a masterpiece and a work in progress simultaneously,” “the Lord is greater than the giants you face,” “you are enough” and “you have been assigned this mountain to show others it can be moved.”

Giselle started bawling. She knew her roommate wasn’t an emotional person.

The fact that she went out of her way, I must really be sick. I must really be sad, she thought.

She reached out to the counselor and was later put on an antidepressant, but didn’t like the feeling of the medication numbing her.

“I was no longer sad, but I was no longer happy,” she said. “I no longer found joy in the things I used to; I didn’t want to talk to anybody. It was just a gray wave of everything.”

After four months, she dropped the antidepressant and turned to counseling only, sometimes going three times a week. Now, she just stops in whenever she feels overwhelmed.

Leaving a legacy

In her 1,034-word scholarship essay, Giselle wrote about how Grand View would give her — for the first time ever — the opportunity to be normal.

Growing up I always knew I was different, I just never knew how much. My mom has always worked two jobs to get us by, so I never see her much. My younger brother has been staying home alone since he was 6, and I’ve had a part time job since I was 14. Not your typical American family. We never ate dinner together, never talked about our day and definitely never did family activities. It never bothered me that I didn’t have a normal life like the rest of my friends, I knew that people are put in certain situations for different reasons, and I’ve always thought that God would never give me more than I could handle.

Being at Grand View would free her from the worry of her legal status, her home life and being discriminated against. She would be able to focus on getting a degree, be involved in student leadership and do “fun college things.”

“I guess to me normal is being able to wake up, go to classes, do my homework, go to work, come back and just be at peace when I go to sleep,” Giselle said.

Giselle also talked about her involvement in extracurriculars in high school and how she planned on furthering her involvement at Grand View.

While working an average of 15-25 hours a week, I have managed to maintain a 3.53 GPA while also participating in soccer, student council and the drama department. I volunteer as much as I can because I know how lucky I am to be granted DACA. I am very appreciative for all of the opportunities I have received to date, so I try my best to give back what I can and that is usually time. I’d like to be involved fully as well as be committed to my education at Grand View but it isn’t financially possible for me to stop working and enjoy my experience. Receiving this scholarship would change my future and make it possible for me to impact my university while bettering myself and my community.

Now, as a tour guide, Giselle often asks incoming students to picture themselves walking to their classes, to the gym and to their dorm.

“Grand View is my home. I’ve made it my home over the last three years, and now my goal is to make it a home for everyone who walks in,” she said. “I don’t ever want anyone to feel like they don’t belong here or there’s no place for them.”

“I really love it here. It’s small enough of a place to make a big enough impact.”

Above all, Giselle just wants to make Grand View a safer place for everyone.

“I definitely want our campus to be more inclusive and acknowledge the diversity that we don’t have or that we do have but just don’t appreciate,” Giselle said.

“As a multicultural ambassador, our goal is to invite everyone to learn about each other’s cultures or differences because diversity isn’t just race or ethnicity. It’s about different sexualities and backgrounds and religions, all of that stuff.”

As a Dreamer, Giselle feels as though it’s her duty to fight for a better life.

A Dreamer is somebody who is constantly fighting and advocating for their rights and the rights of the undocumented community as well as pursuing a better life for themselves, Giselle said.

“I feel like none of our parents brought us here so that we could live a simple, mediocre life and settle for anything. My mom always says I didn’t risk it all for you to not do the best that you could do, and I didn’t leave everything behind so that you could give up when things got tough.”