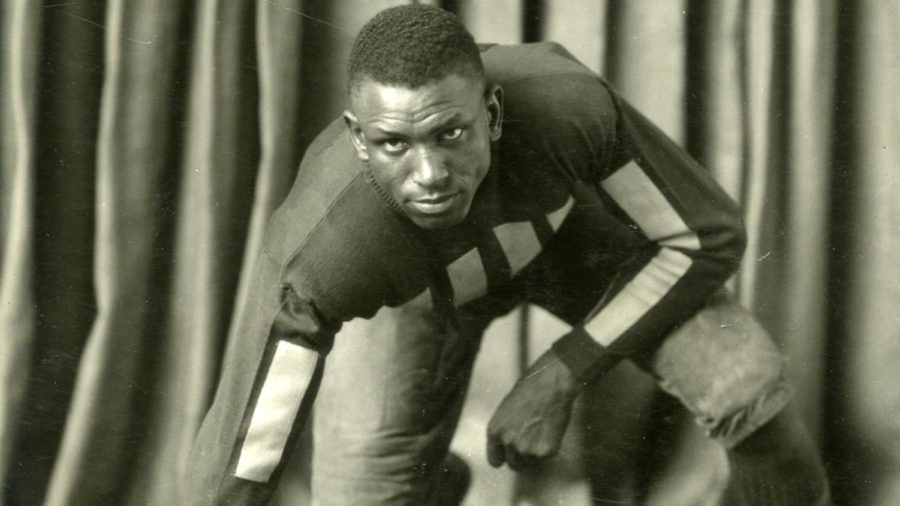

The man who followed Jack Trice– Holloway Smith

Many Iowa State students know about Jack Trice, but Holloway Smith was the man who followed in Trice’s footsteps.

February 3, 2022

As the first African American player in Iowa State history, Jack Trice tore down a long-standing racial barrier. Three years later, another player would follow in his footsteps. Lineman Holloway Smith, the man to follow Jack Trice, pushed the boundaries as a Black Cyclone.

“…[Holloway] Smith, new Cyclone right tackle, is giving promise to be one of the brightest lights that has shone on the Ames line in years,” said the Iowa State vs. Drake, 1926 football program.

Following a season at Michigan State, Smith made an immediate impact. The program states, “In his first game as a Cyclone, although hampered most of the time that Saturday with a broken hand, the giant tackle smeared Grinnell plays for repeated losses, and ripped holes in the Pioneer line large enough to let a truck thru.”

Smith’s athletic ability transcended his color, and he garnered attention from the Iowa State community. In the 1926 program, he was listed as one of Iowa State’s “Cyclone Stars.” He was also prominently featured as one of the first four players in the 1927 Iowa State vs. Kansas State football program. His name was displayed in the “tentative lineup” for the Cyclones, and he was featured in the first row of the team photograph.

However, Smith was not immune to the mistreatment faced by people of color in the early 20th century. Although he received acclaim for his play on the field, he still faced discrimination for his race.

While Smith was allowed to compete for Iowa State, he was limited in where he could actually play due to “gentlemen’s agreements” within the Missouri Valley Conference according to “Sports Law and Regulation: Cases, Materials, and Problems” by Matthew J. Mitten.

“Certain athletic conferences such as the Missouri Valley Athletic Conference (with the exception of Nebraska) systematically excluded black athletes pursuant to so-called ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ that prohibited blacks from participating in league contests. These ‘gentlemen’s agreements’ constituted a series of written rules or tactic understandings precluding black participation in organized sport,” said Mitten.

The discrimination continued off the field as Smith was segregated by his color despite his status as a football player. According to an article on Cyclones.com, Smith was forced to sleep in a segregated funeral parlor, rather than with the rest of the team in a hotel, when traveling to Missouri.

With Smith prohibited from competing against Missouri, the Cyclones were consequently unable to compete at full strength.

The Iowa State Student, now the Iowa State Daily, explained, “The fact that Smith, Iowa State’s latest sensation cannot be used against the veteran Tigers because of a Missouri Valley (Conference) agreement with Southern Schools to not use colored players is the most serious handicap the Cyclones face at the present time. Smith’s work in smearing plays of the opposite side and opening great holes for the Cardinal and Gold is the very thing that Iowa State needs Saturday.”

Although Smith faced discrimination for his race, he was able to graduate from Iowa State and begin his career as a school teacher, according to the Notable Kentucky African Americans Database (NKAAD). Before becoming an NYA supervisor, Smith also worked as a National Youth Administration (NYA) worker.

Despite facing a life of hate and prejudice based on his race, Smith remained devoted to his playing career. He moved the boundaries forward for African Americans and challenged society’s standards during his time as a Cyclone. After his playing days, he dedicated his life to helping others, impacting even more people throughout his life, according to the article on Cyclones.com.