Part two: The end of an age of innocence

January 28, 2022

Editor’s Note: This article is the second part in a five-part series telling the story of Sheila Jean Collins, an Iowa State student who was murdered in 1968. Part one can be read here.

Content Warning: This article contains mentions of sexual and physical assault.

Sheila Collins couldn’t wait. In just a few short minutes, she would finally be on her way home to see her boyfriend, Ira.

Ira was supposed to drive to Ames to pick up Sheila and bring her back to her home in Evanston, Illinois, but the plan fell through, and he wasn’t able to come that Friday.

Previously, Sheila had put her information on a green 3×5 index card and posted it on the “Going My Way?” ride board at the Memorial Union, as many students hoping for a lift did. She hoped that someone going near Evanston, just outside Chicago, would see it and be able to give her a ride home some weekend.

About 7:30 p.m. on Jan. 26, 1968, Sheila received the phone call she had been waiting for. Someone had seen her card on the ride board and offered to give her a ride.

Sheila’s roommate at the time told the Chicago Tribune that Sheila was “elated” to be going home for the weekend to see Ira.

The caller told her to be ready in a few minutes, and Sheila eagerly accepted.

Sheila asked her roommates to walk her to the intersection of Lincoln Way and Beach Avenue, where she was supposed to meet her ride, but they declined. The intersection was only a 5-minute walk from her dorm, Elm Hall.

Sheila packed her suitcase, borrowed $2 in travel money from a friend, threw on a sweatshirt and called her parents to let them know she was coming. Then she made her way to the intersection.

About 8:30 p.m., Sheila hopped into a dark blue Volkswagen, ready for the 355-mile drive home.

By noon the next day, her parents reported her missing.

On Sunday afternoon, Iowa State University veterinarian Roger Hogle and his son, Jeff, were out hunting between Nevada and Colo. Roger Hogle could never have imagined what his son found that day.

“He was looking in the ditches and stuff. I don’t know what he was looking for—he was only 8 years old,” Roger Hogle said. “He said, ‘Dad, Dad! I see a kid’s foot!’”

Jeff Hogle had stumbled across a body, lying in a ditch 5 miles east of Nevada.

“I drove to Nevada, to the sheriff—to the courthouse,” Roger Hogle said. “It’s always been my opinion that they probably knew who it might be because I’m sure they had missing people’s reports by then.”

He told law enforcement about the body and then went back and blocked the road to prevent incoming traffic from finding the scene.

“At that time, there were no houses on that road at all so it was really an isolated place,” Roger Hogle said.

The body that Jeff Hogle had found was that of a petite, brunette young woman, only partially dressed. Her belongings were nearby.

James Collins arrived Monday and confirmed it was his daughter, Sheila.

Sheila was one to stay away from trouble. Her house mother at Elm Hall described her as “the quiet, studious type” in an interview with the Chicago Tribune at the time. “She was well liked and apparently didn’t have any quarrels with anybody. This has stunned all of us here.”

Sheila was born in Elmhurst, Illinois, on Aug. 2, 1949. In the 1950s her parents, James and Muriel, moved their family to Evanston, Illinois, and had Sheila’s younger sisters.

In Evanston, Sheila lived two doors down from Randy Calm, a boy a few years older than she was.

Randy, Sheila and her sisters all ran together in the same neighborhood circles. They played games, chased each other around playing capture the flag and built tree forts in the Collinses’ backyard. Sheila and Randy attended school together but grew apart with age. They both attended Iowa State, where Sheila studied communication, and they always greeted one another in passing.

Randy said that Sheila was a sweet girl. He described her as a “goofball” and said she had a “goofy smile.”

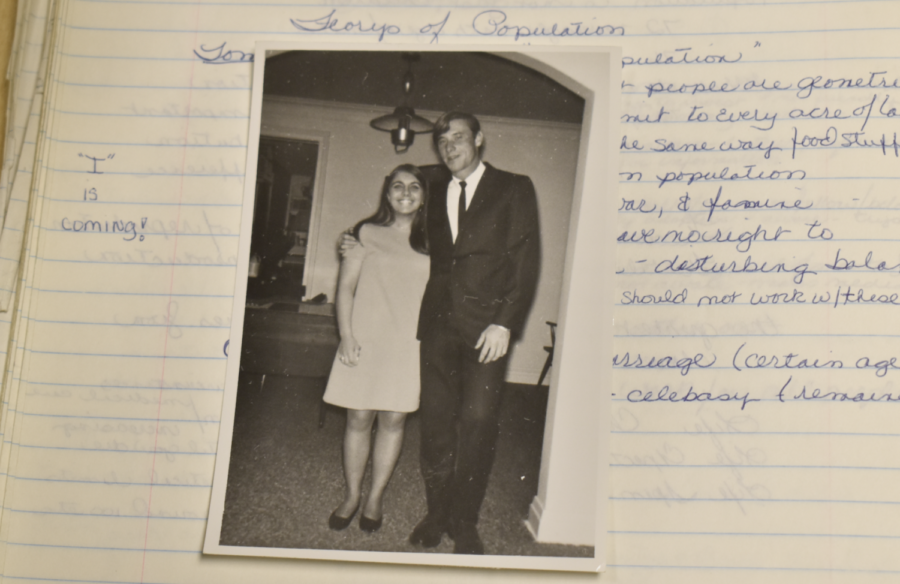

Evanston is also where Sheila fell in love with her high school sweetheart, Ira. The two attended different colleges but were planning to get engaged.

While the distance was difficult, Sheila and Ira’s love stayed strong. A card found in Sheila’s belongings after her death showed the care Ira had for her.

“Needless to say, things would be different if you were nearer to me. That could be the reason why I don’t write that much. I do miss you— and I do love you,” Ira wrote.

Sheila frequently doodled in the margins of her class notes, writing “Ira + Sheila” surrounded by hearts. One note, written when Ira had been scheduled to come to Ames, said “‘I’ is coming!”

Sheila was thinking about this love when she accepted that ride on the evening of Jan. 26. She didn’t second-guess her decision to catch a ride from a stranger.

According to Joyce Durlam, who was an undergraduate student at the time, women largely felt safe on campus. Accepting a ride from the ride board was a common way to get home when not everyone had access to a vehicle. Women had to walk to and from their dorm rooms and sorority houses to study at night, and they weren’t afraid to do so alone.

However, Sheila’s death changed students’ perceptions of safety.

“We were kind of on the cusp, in ’68, ’69, of things really changing,” Durlam said. “There were things kind of brewing beneath the surface, but we were less aware or less concerned about that at that time.”

Sheila’s murder marked the end of the age of innocence for women on campus.

Read part three here.

Contributed reporting by Zack Brown