- News

- News / Politics And Administration

- News / Politics And Administration / Campus

- News / Politics And Administration / City

ISU, Ames Police foresee body cameras

March 2, 2016

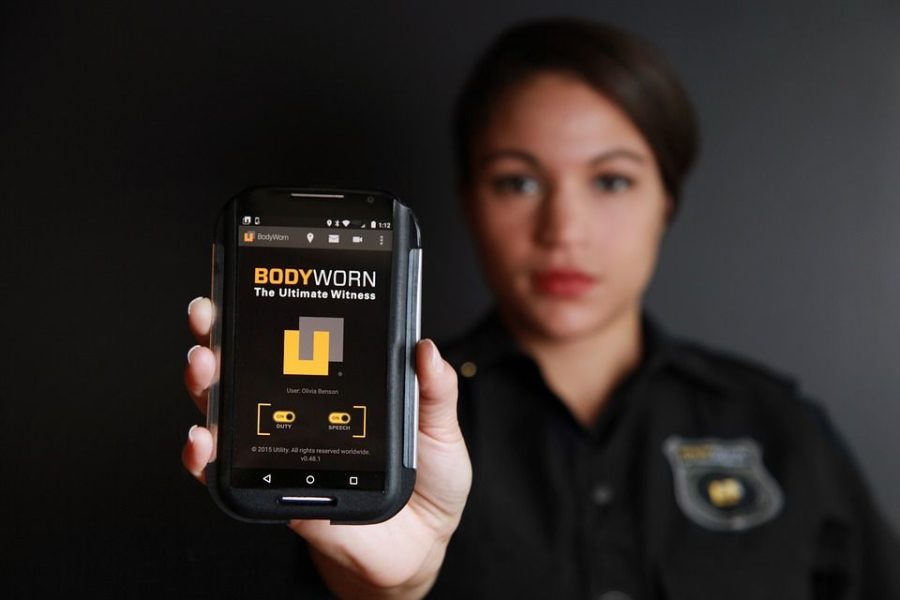

Some no bigger than a pack of cigarettes, body cameras have become a nationally discussed topic on whether they play a supportive, ethical and transparent role in modern law enforcement.

After months of deliberation and research into policy and trials, both the Ames and ISU Police Departments are optimistic of having every officer equipped with body cameras in the near future.

ISU Police Officer Douglas Hicks has been wearing a body camera for about a month, and sees it as a positive piece of equipment.

One of Hicks’ main points is that technology paired with law enforcement is not a new feat.

“In law enforcement there has always been an introduction to new technology, right? So you go from having no cameras in the cars to cars now having cameras,” Hicks said. “You go from not having computers in the cars to getting computers.”

Police have been heavily scrutinized for their use of force during the past few years, particularly after cases such as the deaths of Michael Brown, Sandra Bland and Tamir Rice.

Body cameras — which could create a more transparent view of law enforcement, increase public trust and help provide evidence against false complaints — have several downfalls or kinks in the system that must be polished before they are sent out with law enforcement.

These downfalls include certain privacy rights. For example, should police turn off their body cameras in sexual assault or domestic abuse calls? Who is allowed to view the videos from the body cameras? And where should they be stored?

When discussing body cameras with the public, Jason Tuttle, investigations commander with the Ames Police Department, offered a simple scenario.

“What if we go to someone’s house [and] we’re there because their daughter is having some issues and we find out that she’s on drugs,” Tuttle said. “Say our policy says [that] we videotape all interactions. We videotape that incident, we leave and then the neighbor wants to know why the police were there.”

Tuttle said the neighbor could then go down to the police department and say, “I want a copy of that video,” and there are currently no policies in place that could prohibit the police department from releasing that video — one that infringes on several privacy concerns.

In a bill that is currently being considered in 12 states, including Iowa, law enforcement officers would be required to wear body cameras. As of recently, an Iowa House bill is in consideration that would require officers to wear body cameras whenever they interact with the general public.

No state currently has a law mandating that officers must wear body cameras, however. This allows police departments such as the Ames and ISU departments to take their time when introducing body cameras and allow them to formulate their own policy.

In an article published by the Daily last May, Tuttle said he was hopeful about their prospects with body cameras and that they were formulating a summer committee to research the possibility of the officers receiving the cameras.

Almost a year later, Tuttle said their department just completed three to four months of testing on five to six brands of body cameras to determine what would be best for their department.

One problem that arose from using the body cameras was the ever-changing technology, which warranted Chief of Ames Police Charles Cychosz to give the cameras a few more months to settle before they decide on anything, Tuttle said.

During this time, the Ames Police will have a committee look at the policy portion of the equipment because it is a key factor it would like to have in place before implementing the cameras with every officer.

Ames Police also asked City Council for funding for the cameras and hopes to have the money by the beginning of the next fiscal year: July 1.

City Council also wants to look over the policy for the cameras before the funding is finalized, Tuttle said.

Tuttle also mentioned that to form their policy, they are looking to other departments both nationally and locally to find out what works and what doesn’t.

“We want the community to know when they can ask for those to be turned off or when we will turn them off [and] when we won’t,” Tuttle said. “So there needs to be some dialogue that we’re going to have to have with the community about those things, too.”

Aaron Delashmutt, interim chief of ISU Police, said that he was equally positive about the body cameras in the aforementioned Daily article.

“More times than not they help us solve crimes, they help us resolve situations, and they help the officer,” Delashmutt said previously.

Another problem that arises with body cameras, however, is the fact that sometimes the camera cannot see everything in the situation, as the camera is usually strapped to chest of the policer officer and is only facing off the officer’s body.

This is where Hicks said that while he is in full support of the body cameras, it is not the most reflective of what is happening in the situation.

Discussing a human component, Hicks mentioned that the camera can often distort depth perception in the video, which could play into factor when the video is under review about the use of force and when it was okay to take or not take action.

“It doesn’t hear at the same quality that I can hear. It doesn’t have feelings, it doesn’t smell, it can’t see certainly the same that I can,” Hicks said. “So, anytime you deal with use of force or just law enforcement in general, there is always going to be that human component.”

Hicks said that he believes people look to that human component and that as law enforcement, they want the public to trust them.

“I understand that with society today, that trust can be questioned,” he said. “When, generally, it is the actions of a few that causes the masses to be questioned, and if you’re going to be in law enforcement than you have to understand that.”