Alumnus fights disease with data, encourages students to get involved

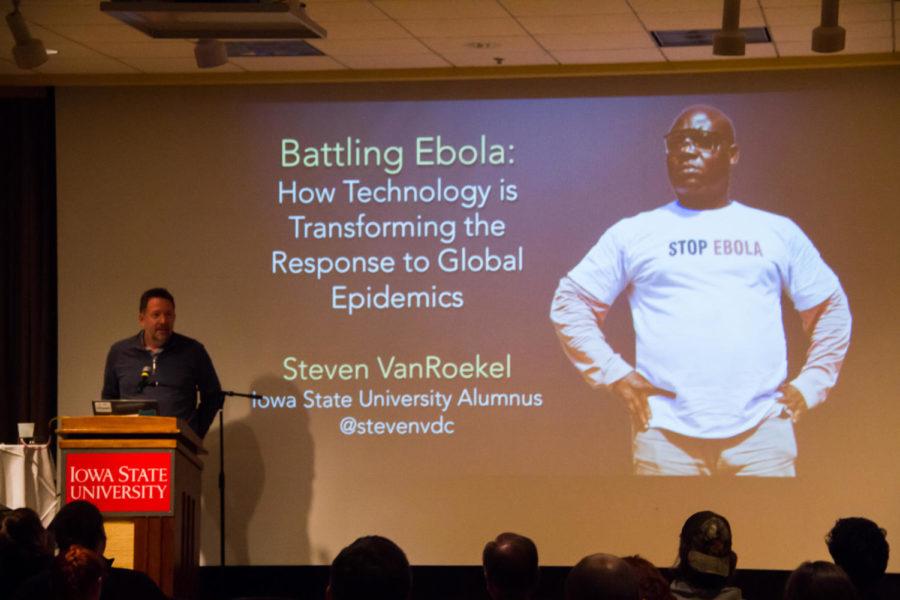

Steven VanRoekel, former USAID Chief Innovation Officer, gives a lecture on how technology has changed the way we as a world handle epidemics in the Sun Room of the Memorial Union Oct. 1.

October 6, 2015

While the world was shielding itself from the Ebola outbreak in 2014, Steven VanRoekel and his team at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) dove head first into West Africa to try to conquer the disease.

VanRoekel, ISU alumnus and former chief innovation officer at the agency, described his role, and technology’s role, in fighting the outbreak during his lecture at Iowa State, “Battling Ebola: How Technology is Transforming the Response to Global Epidemics.”

VanRoekel worked with technology for 14 years at Microsoft as an assistant to Bill Gates, helping launch Windows XP, the Xbox and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

“I never thought I would get any higher on the impact I was having on the world [at the Xbox launch],” VanRoekel said.

After leaving Microsoft, VanRoekel was the chief information officer of the United States, working directly for the White House.

President Barack Obama’s administration asked VanRoekel to work with USAID in the wake of the Ebola outbreak.

Having a lot of experience with technology, but none with medicine, VanRoekel said he first assumed the role of data in the Ebola epidemic might involve mobile applications with data, information and maps.

The first step to handling the situation in West Africa for VanRoekel involved a sort of immersion. He went to West Africa in fall 2014 to wrap his head around what was going on.

After visiting Liberia, VanRoekel realized there was very low mobile connectivity in the region.

VanRoekel said both technology literacy and literal literacy issues were prevalent. He realized his first assumption about the role of technology in the fight against Ebola would not suffice.

VanRoekel decided the first role of technology would be collecting data regarding the status and spread of Ebola.

“We spent an entire afternoon writing down what data went where,” VanRoekel said. “It was mind-numbing to think about this, but we had to start somewhere.”

VanRoekel and his team used telephones to transmit data when possible, but often had to transport information via messengers on motorcycles.

The second role, VanRoekel said, was communications and outreach.

“First and foremost, [we] had to find the communication dark spots and get satellite communication there,” VanRoekel said.

VanRoekel’s team used satellite communication, local town meetings, radio communication and posters to inform locals about the spread of Ebola.

The third opportunity for technology was rapid diagnostics, VanRoekel stated.

“We actually worked with the U.S. Navy to set up a lab in a container,” VanRoekel said.

His team hired contracted helicopter pilots to transport blood samples to the diagnostic labs to get blood test results quickly. Its goal was to have a 24-hour turn around time, which it met and then surpassed.

The last area to use technology was information regarding personal protective equipment, VanRoekel said.

He explains the issue with the protective suits was that they were not designed for the heat of the West African summer.

“[Doctors] could spend about 30 minutes in the suit before it became unbearable,” VanRoekel said.

VanRoekel said it took about 30 or 40 minutes to carefully get out of the suits without spreading any of the bodily fluids that may have been on them.

VanRoekel said one of the biggest issues with the suits was that it was difficult to get human-to-human contact between the doctors and patients when the patients could only see the doctor’s eyes.

USAID gathered designers and engineers to invent a new suit that was more functional and allowed for greater human interaction between the doctors and patients.

VanRoekel said the agency helped Liberians and the global community control the Ebola virus. It also introduced health practices to prevent future outbreaks.

VanRoekel said he wanted the audience to see that someone from Ames can have and impact on his or her community, government and world.

“We live in a great nation full of great people,” VanRoekel said, urging students to think about public service and getting involved. “It’s not the government, it’s our government.”