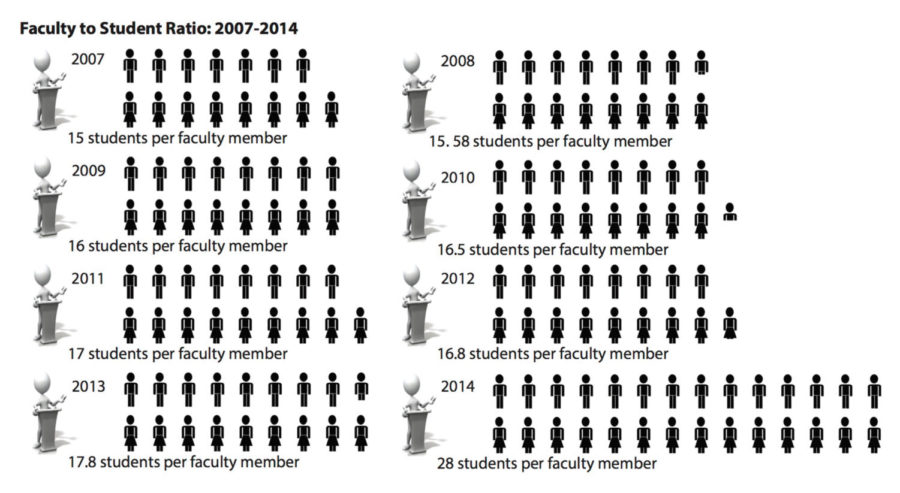

Student-Faculty ratio experiences steady increase

The student-faculty ratio has been changing since 2007, when there were 15 students per faculty member, to 2014, where there are 28 students per faculty member.

October 10, 2014

The student-faculty ratio is just one of the many things that the university looks at as a measure of what it is doing to help students succeed in their degree programs.

With Iowa State enrollment numbers at a record high, university officials are looking for ways to “expand the capacity of the institution” while still keeping a high-quality student experience, President Steven Leath said during his presidential address at the start of the fall semester.

In the last ten years, the ratio of full-time students to full-time faculty has grown from 16-1 to 19-1 as of the 2013-2014 academic year. The ratio in 2004 was 16-1, dropping down to 15 in 2005 and 2006 and raising back up to 16.

“It’s something that we definitely keep our eye on,” said Jonathan Wickert, senior vice president and provost. “It’s useful to look at because it can be quantified and it’s something we can compare against other schools.”

Iowa State is part of an official peer group made up of schools that are similar to be used for comparison purposes, including Ohio State, North Carolina State and Purdue.

Wickert said in terms of student to faculty ratio, Iowa State ranks near the middle.

“President Leath has made a commitment to invest in faculty hiring, which will help up us to reduce the student faculty ratio a bit,” Wickert said. “We hired more faculty this past year than we ever have before, and we have searches underway to hire 130 more. If this year goes the way we all want it to go, we’ll be bringing in yet an even larger group of new faculty through hires made this year.”

Leath said during his presidential address that 105 new tenure or tenure-track faculty were hired this academic year, bringing the total to 245 new hires in less than three years. At his address, Leath stated that he believes Iowa State is the only university in the country that has hired over 100 tenure-track faculty two years in a row.

Wickert said their goal is to find the correct balance between building the size of the faculty and keeping tuition affordable.

“We’re all very proud that our tuition is the lowest among our peer group,” Wickert said.

In addition to looking at student-faculty ratio, Wickert said the university invests in several other programs to ensure students’ academic success, including learning communities, supplemental instruction and tutoring.

The Course Availability Group is one resource focused on providing enough seats in the classes students need. David Holger, associate provost for academic programs and dean of the graduate college, has been the chair of the Course Availability Group since it began about ten years ago.

The group’s initial goal was to try and predict the courses needed by first-year incoming students so that students could leave orientation with a schedule of classes that would let them start making progress toward a degree.

When enrollment wasn’t growing so fast, analyzing introductory classes was enough, Holger said.

“At the time the enrollment started growing, there were spaces in lots of classes,” Holger said. “As soon as we started getting fairly significant increases in the number of students coming, then we had to start worrying about spring semester, too, and then second-year courses.”

The registrar and admissions staff decided to put together a team that worked primarily with the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences to carefully analyze the number of students who started last fall, in what majors and how many are continuing in order to predict how many seats are needed in the courses.

“It doesn’t mean everyone gets their first-choice time or first-choice section,” Holger said. “But over the last three to four years, that predictive model has become sophisticated enough that we’re pretty much hitting the mark.”

The course availability group meets once a month and includes about 35 representatives from all colleges, including the associate dean for undergraduate programs for all the colleges, an adviser from each college and a group of people from student affairs. Right now they are finalizing what is needed for spring semester.

He said that a complication with the registration process is that students don’t always put their names on waiting lists if a class is full. If students put their names on wait lists, Holger said it would help identify places where demand is not being met.

“Everybody was saying this year was probably the best job that’s been done for fall semester ever,” Holger said. “Partly that’s because the prediction is getting better. Also, there are fewer students who aren’t registering on time. I think the word is out there that if you want to get the classes and sections and you want, when you can register you should register.”

While the student to staff ratio is 19-1, some students in lecture classes do not see the benefits of that ratio.

Mikayla Dolch, freshman in agricultural and life sciences education, registered for classes this summer at one of the earlier orientation dates. Dolch said she did not have a problem getting into classes due to available seats, but the main issue was trying to get the classes she wanted to work with her schedule.

Most of Dolch’s classes are in large lecture halls; however, some also include additional discussion sessions throughout the week with fewer students. Coming from a smaller high school in southwest Iowa, she said she misses the small class environment.

“For high school, we were very ‘spoon-fed,’” Dolch said. “But with smaller classes, I felt like I could retain the information a little better and understand it more. I could also ask questions without feeling intimidated.”

Cole Anderson, junior in biology, said his freshmen science classes had around 300 people, and his classes now still have around 200 students in each lecture.

“You never get that one-on-one feel with big classes,” Anderson said. “You work in small groups, but the professor never knows your name.”

While his biology classes have recitation times with fewer students, Anderson said he still wishes his classes had smaller lectures.

“Recitation and class itself don’t coincide all the time, so you’re left feeling more confused,” he said. “Sometimes the teaching assistant has one way of teaching a subject while the professor has another.”

In regards to small classes versus large lectures, Holger said they are constrained by the number of classrooms in certain sizes.

“Most departments would say they don’t want to offer one large section of a class, because that’s the only time students can take that class,” Holger said. “The tendency is to say if you have 200 students taking a class this term, it’s probably better to have two sections of 100. So the classes that are in the big lecture halls are ones where they might be several thousand students taking the class, so you have four sections that are all big.”

In terms of an optimal average class size or student to faculty ratio, Wickert said there is not a specific number.

“The student to faculty ratio for a school like us aggregates across so many different degrees and programs and colleges,” Wickert said. “As you get through your degree program and take more specialized elective classes, the class sizes become smaller. You will always see some variability.”

A key to providing a high-quality educational experience for students is providing the classes they need, said Holger.

“If we can’t do that, then we’re starting from a losing position,” he said. “You need to first make sure that you’re providing the academic environment that lets them make progress and be successful academically. There are other things, too, but this is one where I think we did it right.”