Ames PD Mental Health Advocate declares “mental health crisis”

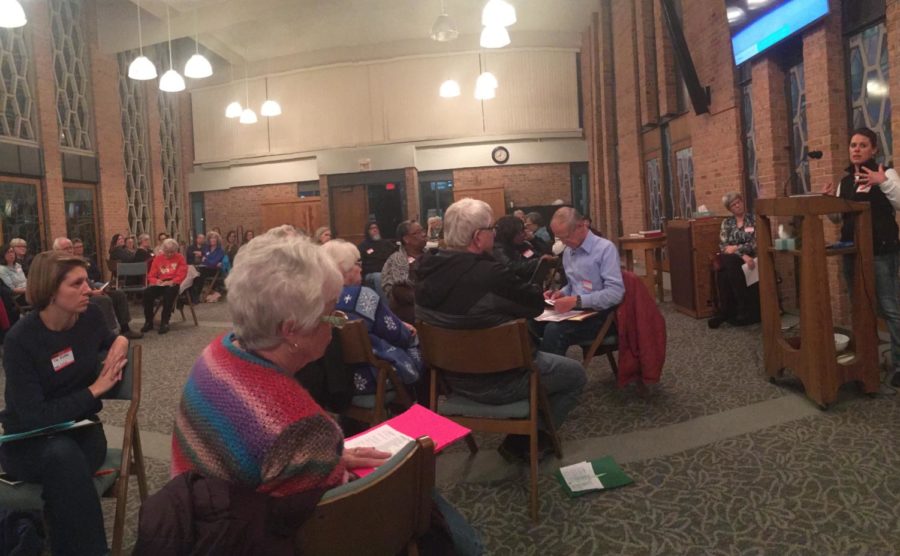

Julie Saxton gives a first-hand account of the Ames mental health crisis in the Bethesda Lutheran Church common area.

November 9, 2017

An Ames mental health crisis has been declared.

More than 100 members of Ames area churches filled the common area of Bethesda Lutheran Church to share stories and worries about the mental health situation in Story County.

Ames Police Department Mental Health Advocate Julie Saxton took the podium to make her urgent declaration.

“We are in a mental health crisis. Ames PD received almost 1,600 calls concerning mental health issues in the last fiscal year,” Saxton said. “This is not sustainable. It isn’t fair [for the mentally ill] and we lack the funding and personnel to deal with it.”

Saxton’s points were echoed throughout the meeting, which was hosted by AMOS (A Mid-Iowa Organizing Strategy), which focuses on community action.

People discussed in small groups how mental illness affects their lives, whether it be internal afflictions or problems with friends and family. People voiced concern with the stigmas around mental illness and the lack of stabilization resources available for mental illness patients.

“We don’t want the police departments to become the de facto mental health care providers, but that’s what seems to be happening,” said Linda Hanson, clinic director for Primary Health Care Inc.

Hanson described a pattern of unstable events many mental health patients experience: They undergo a destabilizing event, such as being displaced from their homes, and need care. They seek care only to find few providers with long waiting lists, or get turned away due to lacking facilities. Many aren’t allowed to drive due to their conditions, or simply can’t find properly trained health care specialists nearby.

“People in our community deserve to have the proper care from within the community,” Hanson said. “They shouldn’t have to leave.”

Things can go downhill rapidly when mental health patients are unable to receive treatment, especially if they don’t have homes. People who need care and lack outside support often end up homeless or in prison.

According to Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit mental health organization, 15 percent of incarcerated inmates and 33 percent of homeless people suffer from serious and untreated mental illnesses.

Mental health care providers are so few and far between because it’s not an attractive position, Hanson insisted. The field receives low worker reimbursement and often “burns out” staff with massive workloads.

Saxton developed a program in collaboration with RSVP (Retired Seniors Volunteer Program) called Community Companions. The program pairs low risk mental health patients with retired social workers to bring stability to their lives. Retirees with a specialty for mental health care can contact RSVP for more information.

Program’s like Saxton’s give people hope for mental health reformation in the future.

“I’m hopeful people [with mental illnesses] will get the housing, services and care they need,” said Hanson.