Pakistan’s ruling coalition collapses amid dissent

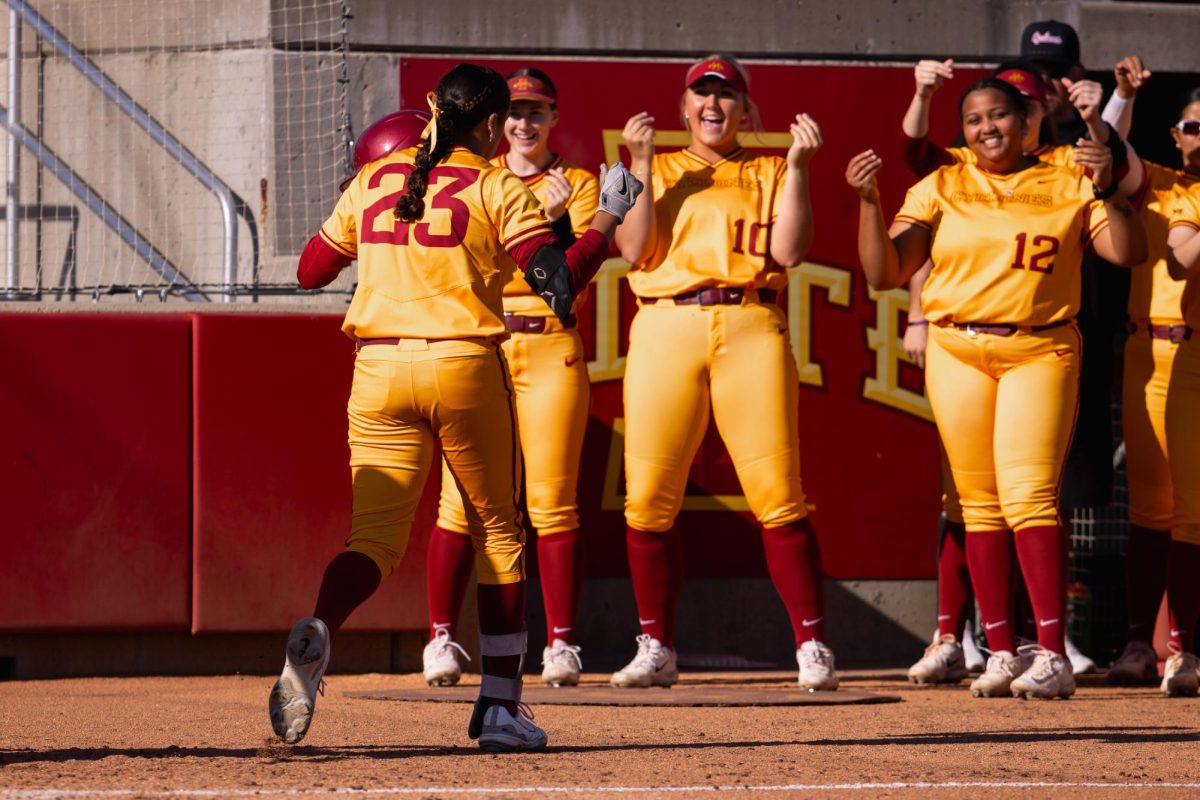

A Pakistani examines a collapsed portion of a girls’ school wrecked by militants with explosive on the day before in Badabair near Peshawar, Pakistan on Monday. Pakistan banned the Taliban after they claimed responsibility for one of the country’s worst-ever terrorist attacks, toughening its stance against Islamic militants just one week after U.S. ally Pervez Musharraf was ousted from power. Photo: Associated Press/Muhammad Sajjad

August 25, 2008

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — Pakistan’s ruling coalition collapsed Monday, torn apart by internal bickering just a week after Pervez Musharraf’s ouster and underscoring fears that the government would be distracted from its fight against Islamic extremists.

Militants have stepped up their campaign of violence in recent months, prompting the government Monday to ban the Taliban. The move came after the Islamic militant group claimed responsibility for twin suicide bombings against one of Pakistan’s most sensitive military installations that left 67 dead.

The breakdown of the fragile 5-month-old civilian government clears the way for the party of slain former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto to tighten its hold on the government; the West hopes it will make good on pledges to combat terrorism.

Nawaz Sharif, another former premier, announced Monday that he was pulling out of the coalition because it failed to restore judges fired by Musharraf or agree to a neutral replacement for the ousted president.

He blamed Bhutto’s widower and political successor, Asif Ali Zardari, for the breakup, and named a retired judge to run against Zardari in the Sept. 6 presidential election by lawmakers.

However, Sharif vowed to play a “constructive” role while in the opposition.

“We don’t want to be instrumental in overthrowing any government. We don’t have any such intentions,” Sharif told a news conference.

His move is not expected to trigger new elections.

A major opposition party has already backed Zardari’s presidential bid. That group, together with smaller parties and independents could plug the gap in the government’s parliamentary majority.

The shake up caps a week of upheaval in Pakistan’s political landscape.

Musharraf quit Monday, nine years after he seized power in a military coup, to avoid impeachment charges.

With their common foe gone, the coalition that drove him from office frayed over unkept promises to restore the judges and Zardari’s decision to seek the presidency.

Concern that the turmoil was distracting the government from tackling urgent economic and security issues was borne out Thursday when twin Taliban suicide bombers killed 67 people at an arms factory near the capital.

Interior Ministry chief Rehman Malik announced Monday that the group responsible for the attack, the Tehrik-e-Taliban, was banned. He said the militants had “created mayhem” in the nuclear-armed nation.

Anyone caught aiding the Taliban in Pakistan — which will have its bank accounts and assets frozen — faces up to 10 years in prison.

The ban came 24 hours after Pakistan rejected a Taliban cease-fire offer in Bajur tribal region, a rumored hiding place for Osama bin Laden, where an army offensive has reportedly killed hundreds in recent weeks.

“This organization is a terrorist organization and created mayhem against public life,” said Malik.

The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, an umbrella group of militants along the rugged Afghan border set up last year, has claimed responsibility for a wave of suicide bombings in the last half year that have killed hundreds.

Its leadership is formally separate from the Taliban movement which was swept from power in Afghanistan in 2001.

However, some of its members are believed to help recruit, arm and train volunteers for the Taliban-led insurgency against government and NATO troops on the Afghan side of the frontier.

“I think at the moment they definitely have the upper hand, and we need to do something better,” Zardari told the British Broadcasting Corp. shortly before the ban was announced.

Whatever the world, Pakistan included, has done in the last 10 years to fight terrorism, the presidential hopeful said, “it’s not working.”

Malik said the Taliban group was not banned more quickly because the provincial government had been trying to negotiate with it to secure peace. The restrictions would include offering financial aid, handing out propaganda or providing any other type of support.

The militants, meanwhile, called the ban “meaningless.”

“We are neither registered nor do we have any bank accounts,” said Muslim Khan, spokesman for the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, which has threatened to step up its campaign of violence nationwide unless the military ends its operations in Bajur. “We are slaves to no one.”

Violence continued to flare Monday.

Eight were killed in a pre-dawn rocket-and-bomb strike on the home of provincial lawmaker Waqar Ahmed Khan in Swat, a former tourist destination-turned-battlefield, police and the politician said. His brother, two nephews and five guards were killed.

Meanwhile, a Geneva prosecutor said Monday he has dropped money laundering charges against Zardari, saying an 11-year investigation has produced too little for him to continue. Prosecutor General Daniel Zappelli noted that the Pakistan prosecutor had also dropped his corruption cases against Zardari.

The move comes eight months after Zappelli dropped charges against the assassinated Bhutto.